Yes, birds are considered reptiles according to modern phylogenetic taxonomy. This may surprise many, but the scientific consensus confirms that birds are classified as reptiles because they share a common ancestor with crocodilians, lizards, snakes, and turtles. In fact, birds are not just related to reptiles—they are a specialized subgroup within the reptile clade known as Archosauria. The long-held distinction between birds and reptiles based on appearance or behavior no longer holds up under genetic and fossil evidence. Today’s understanding of evolutionary biology shows that are birds considered reptiles is more than a technicality—it reflects deep biological truths about descent and adaptation.

The Evolutionary Link: How Birds Descended from Dinosaurs

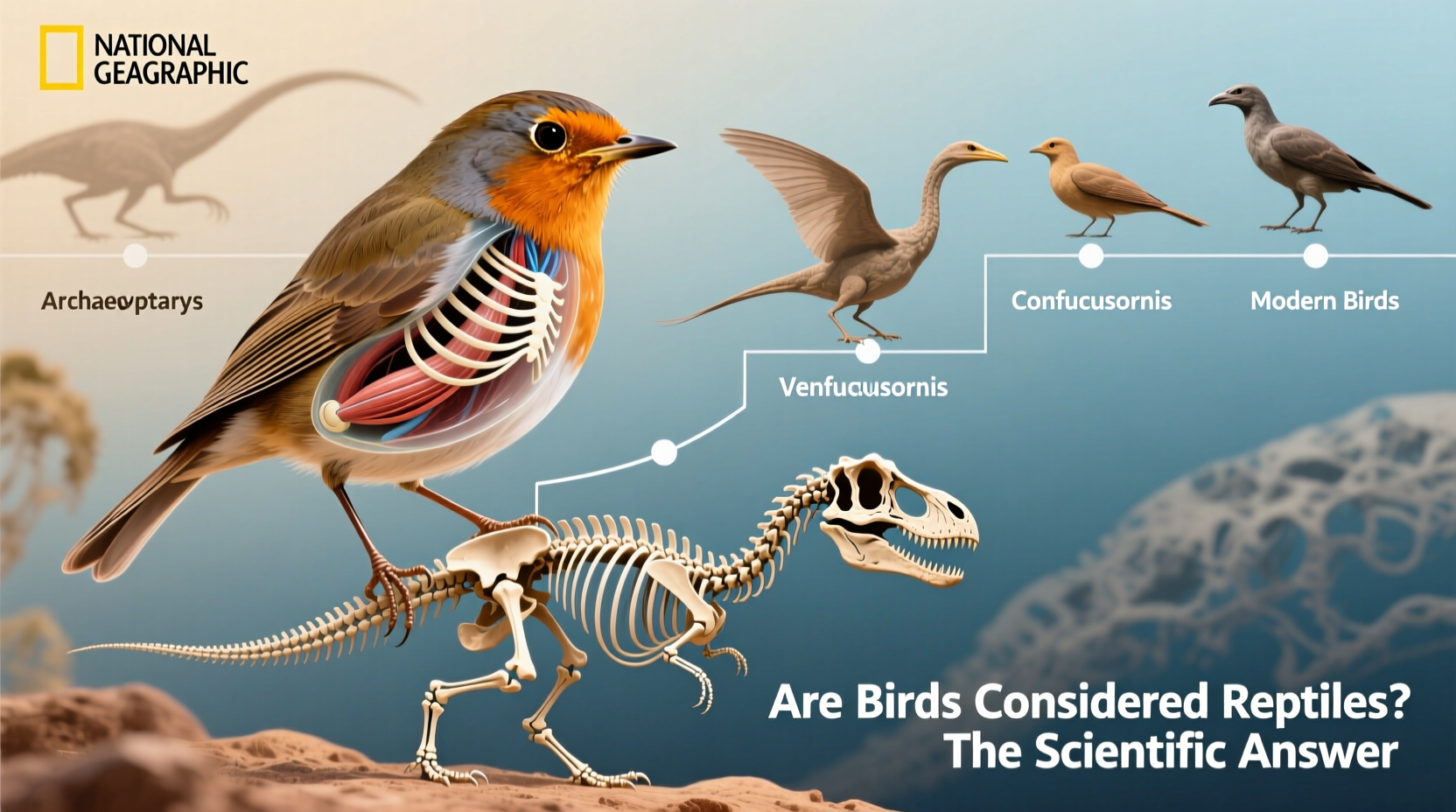

Birds evolved from small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago. Fossils like Archaeopteryx, discovered in Germany in the 19th century, display clear transitional features—feathers, wishbones, and three-fingered hands—linking them directly to carnivorous dinosaurs such as Velociraptor. Over millions of years, these feathered dinosaurs developed adaptations for flight, including hollow bones, keeled sternums for muscle attachment, and efficient respiratory systems.

Modern genetic and anatomical studies reinforce this connection. For example, both birds and reptiles lay amniotic eggs with protective membranes, have scales (which feathers evolved from), and share similar skeletal structures. Crocodiles, the closest living relatives to birds among non-avian reptiles, share four-chambered hearts and advanced parental care behaviors—traits once thought unique to mammals or birds.

Why Modern Taxonomy Classifies Birds as Reptiles

Traditional classification systems grouped animals by physical traits: birds flew and had feathers; reptiles crawled and had scales. But modern systematics uses cladistics—a method that groups organisms by common ancestry rather than superficial characteristics. Under this framework, any group must include all descendants of a common ancestor to be valid (a “monophyletic” group).

Because birds descended from reptilian ancestors and share more recent common ancestry with crocodiles than crocodiles do with lizards or turtles, excluding birds from Reptilia would make the class paraphyletic (incomplete). Therefore, scientists now define Reptilia to include birds, making Aves (birds) a subgroup of Reptilia. This reclassification isn’t arbitrary—it’s grounded in DNA analysis, embryology, and paleontology.

| Trait | Birds | Non-Avian Reptiles | Shared Ancestry Indicator? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amniotic Egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Scales/Feathers | Feathers (modified scales) | Scales | Yes |

| Skeletal Structure | Hollow bones, fused clavicles | Dense bones, separate clavicles | Partial (adaptations differ) |

| Heart Chambers | Four | Crocs: Four; Others: Three | Yes (especially with crocodilians) |

| Genetic Similarity to Crocs | ~90% genome similarity | N/A | Strong evidence of shared lineage |

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Reptiles

Many people resist the idea that birds are reptiles because of ingrained cultural and linguistic categories. Here are some widespread misconceptions:

- Misconception 1: Reptiles are cold-blooded, so birds can’t be reptiles.

While most reptiles are ectothermic (relying on external heat), birds are endothermic (generating internal body heat). However, metabolism doesn’t determine taxonomic placement. Some reptiles show partial endothermy (e.g., leatherback sea turtles), and metabolic shifts occur throughout evolution. - Misconception 2: Feathers make birds fundamentally different.

Feathers evolved from reptilian scales. Fossil evidence shows scaled dinosaurs with proto-feathers, indicating a gradual transition. Keratin—the protein in feathers—is also found in reptile scales and claws. - Misconception 3: If birds are reptiles, why are they taught separately?

Educational curricula often separate birds and reptiles for simplicity, especially at early learning levels. But university-level biology and peer-reviewed research recognize avian inclusion in Reptilia.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds vs. Reptiles

Culturally, birds and reptiles occupy vastly different symbolic spaces. Birds are frequently associated with freedom, spirituality, and transcendence—think of doves representing peace or eagles symbolizing national strength. In contrast, reptiles like snakes and crocodiles often evoke fear, danger, or cunning (e.g., the serpent in Eden).

These symbolic distinctions influence how we categorize animals emotionally, even when science tells a different story. Indigenous traditions, mythologies, and religious texts rarely acknowledge the biological kinship between hawks and lizards. Yet recognizing that birds are reptiles invites us to reconsider our anthropocentric views of nature and appreciate evolutionary continuity.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Naturalists

For birdwatchers, understanding that birds are reptiles enhances appreciation of their evolutionary journey. Observing behaviors like sun-basking (seen in vultures and roadrunners) mirrors thermoregulatory habits of lizards. Nesting strategies, egg-laying, and even certain vocalizations have parallels in crocodilian species.

When planning birdwatching trips, consider visiting regions where ancient lineages persist:

- Galápagos Islands: Home to flightless cormorants and marine iguanas—both adapted to aquatic life in ways that highlight evolutionary flexibility.

- Australia: Features ancient bird groups like cassowaries and emus, whose dinosaur-like appearance underscores their reptilian heritage.

- Everglades National Park: Offers sightings of wading birds alongside American alligators—living representatives of the archosaur lineage.

Use binoculars with UV filters; some bird feathers reflect ultraviolet light, an adaptation rooted in visual systems shared with certain reptiles. Also, consult field guides that incorporate phylogenetic trees to better understand relationships between species.

How Scientists Verify Avian-Reptilian Relationships

Researchers use multiple lines of evidence to confirm that birds are reptiles:

- Fossil Record: Transitional fossils like Anchiornis and Xiaotingia show feathered dinosaurs predating Archaeopteryx, filling gaps in the evolutionary timeline.

- Comparative Anatomy: Detailed studies of skull structure, pelvic girdles, and lung design reveal striking similarities between birds and theropods.

- Molecular Biology: Genomic sequencing shows high DNA overlap between birds and crocodilians—higher than between mammals and reptiles.

- Embryology: Developing bird embryos exhibit teeth buds, tails, and clawed digits—features lost in adults but present in reptilian ancestors.

To stay updated on new discoveries, follow journals like Nature, Science, and The Auk: Ornithological Advances. Museums with paleontology exhibits—such as the American Museum of Natural History or the Royal Tyrrell Museum—also provide accessible insights into avian origins.

Regional Differences in Classification and Education

While the scientific community globally accepts birds as reptiles, educational standards vary by country. In the United States, K–12 textbooks often maintain a traditional separation. In contrast, European and Australian curricula increasingly integrate cladistic principles.

If you're a student or educator, verify your local curriculum’s approach. Check whether biology standards align with organizations like the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology (SICB) or the Paleontological Society. Encourage critical thinking by asking: Should classification be based on appearance or ancestry?

Future Research and Ongoing Debates

Although the consensus is strong, debates continue about finer points of avian evolution. Questions remain about:

- The exact timing of flight evolution

- Whether feathers first evolved for insulation or display

- How brain complexity increased so rapidly in early birds

New technologies like synchrotron scanning and proteomic analysis of fossilized tissues are shedding light on these issues. Citizen science projects, such as eBird and iNaturalist, also contribute data that help track behavioral and ecological patterns linking modern birds to ancestral traits.

FAQs: Common Questions About Birds and Reptiles

Are birds cold-blooded like reptiles?

No, birds are warm-blooded (endothermic), unlike most reptiles, which are cold-blooded (ectothermic). However, metabolic rate does not override evolutionary ancestry in classification.

If birds are reptiles, should they be called 'avian reptiles'?

Yes, technically birds are avian reptiles, while snakes and lizards are non-avian reptiles—similar to how bats are mammals despite flying.

Do all scientists agree that birds are reptiles?

Virtually all evolutionary biologists and paleontologists accept this classification based on overwhelming evidence from fossils, genetics, and anatomy.

Can birds interbreed with reptiles?

No. Despite shared ancestry, birds and reptiles diverged too long ago (over 200 million years) for viable hybridization. Reproductive isolation is complete.

Does this mean my pet parrot is a lizard?

No, your parrot isn’t a lizard, but both lizards and parrots belong to the larger reptile group. Think of it like humans and whales both being mammals—one swims, one doesn’t, but they share a common ancestor.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4