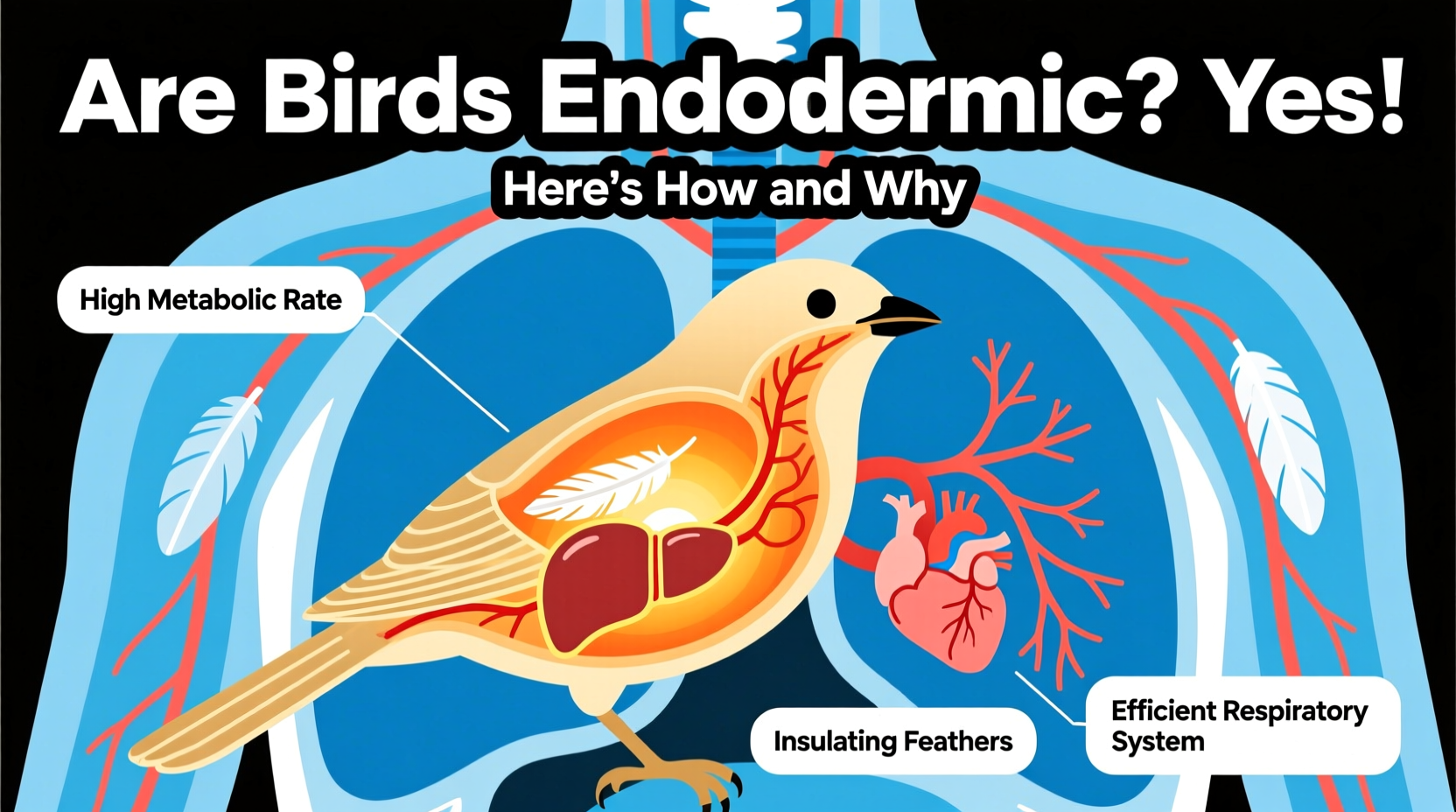

Yes, birds are endothermic, meaning they maintain a constant internal body temperature through metabolic processes, regardless of external environmental conditions. This ability to produce and regulate their own heat is a defining characteristic of avian physiology and places them among the few fully endothermic vertebrate groups—alongside mammals. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'how do birds regulate body temperature' reflects widespread curiosity about the mechanisms behind this crucial adaptation. Endothermy in birds enables high levels of activity, supports flight, and allows survival across diverse climates—from Arctic tundras to tropical rainforests.

The Biological Basis of Avian Endothermy

Endothermy refers to the capacity of an organism to generate internal heat via metabolic activity, primarily in organs like the liver, brain, and especially skeletal muscles. In birds, this process is highly efficient due to several specialized physiological traits. Most bird species maintain a core body temperature between 40°C and 42°C (104°F–107.6°F), which is notably higher than most mammals. This elevated temperature enhances enzyme efficiency, accelerates nerve conduction, and supports rapid muscle contractions essential for sustained flight.

Birds achieve thermal stability through a combination of high basal metabolic rates (BMR), insulation, and behavioral strategies. Their BMR is typically 5–10 times higher than that of similar-sized reptiles. This intense metabolism requires substantial energy intake; many small birds consume up to 20% of their body weight in food daily. For example, a hummingbird may visit hundreds of flowers each day just to sustain its energy needs.

Insulation: Feathers and Fat Layers

One of the most effective adaptations supporting endothermy in birds is the presence of feathers. Unlike mammalian hair, feathers provide superior insulation by trapping layers of warm air close to the skin. Contour feathers form the outer layer, while down feathers—soft, fluffy plumage beneath—act as thermal barriers. During cold weather, birds fluff their feathers to increase trapped air volume, enhancing insulation.

In addition to feathers, some birds develop subcutaneous fat deposits before winter or migration. Waterfowl such as ducks and geese accumulate fat reserves that serve both as energy stores and additional insulation against cold water. Penguins take this further with dense feathering and thick blubber, allowing them to thrive in Antarctic environments where temperatures can drop below -40°C.

Metabolic Heat Production Mechanisms

Birds generate heat not only through normal cellular respiration but also via non-shivering thermogenesis (NST), particularly in specialized tissues. While mammals rely heavily on brown adipose tissue (BAT) for NST, birds lack significant BAT deposits. Instead, they utilize alternative pathways involving skeletal muscle and the liver.

A key mechanism in avian heat production is facultative thermogenesis, where mitochondria in muscle cells uncouple oxidative phosphorylation from ATP synthesis, releasing energy directly as heat. This process is regulated by hormones such as thyroid hormone and catecholamines. Shivering thermogenesis also occurs during acute cold exposure, where rapid muscle contractions produce heat without movement.

Studies show that passerine birds like chickadees and sparrows can elevate their metabolic rate by over 300% during freezing conditions. Some species even enter controlled hypothermia at night—known as torpor—to reduce energy expenditure, temporarily lowering body temperature by several degrees.

Evolutionary Origins of Bird Endothermy

The evolution of endothermy in birds remains a topic of scientific investigation, but evidence suggests it arose gradually within theropod dinosaurs, the ancestors of modern birds. Fossil records, bone histology, and isotopic analyses indicate that certain dinosaur lineages exhibited elevated metabolic rates and possibly partial endothermy.

Feathers initially evolved for display or insulation rather than flight, suggesting early thermoregulatory functions. As predatory theropods became more active and agile, increased aerobic capacity and heat retention likely provided selective advantages. The transition to full endothermy would have been critical for nocturnal activity, parental care, and colonization of cooler habitats.

Molecular clock estimates and phylogenetic studies place the emergence of true avian endothermy around 150–200 million years ago, coinciding with the appearance of Archaeopteryx and other early avialans. Over time, natural selection favored individuals capable of maintaining stable internal temperatures, leading to the sophisticated systems seen today.

Comparative Physiology: Birds vs. Mammals vs. Ectotherms

To better understand avian endothermy, it helps to compare birds with other animal groups. The table below outlines key differences:

| Feature | Birds | Mammals | Ectotherms (e.g., Reptiles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature Range | 40–42°C | 36–39°C | Varies with environment |

| Metabolic Rate | Very high | High | Low to moderate |

| Primary Insulation | Feathers | Fur/hair | Scales (minimal insulation) |

| Heat Production Method | Muscle/liver NST, shivering | Brown fat, shivering | Behavioral basking |

| Energy Requirements | Extremely high | High | Low |

This comparison highlights how birds occupy a unique niche: they match or exceed mammals in metabolic intensity while using distinct anatomical solutions. Unlike ectotherms such as lizards or snakes, which depend on external heat sources like sunlight to raise body temperature, birds remain active even in low ambient temperatures.

Ecological Advantages of Being Endothermic

Endothermy confers numerous ecological benefits. It allows birds to inhabit extreme environments where ectotherms cannot survive. For instance, the common raven thrives in Alaska’s winters, and the bar-headed goose migrates over the Himalayas at altitudes exceeding 8,000 meters, where oxygen levels are less than half those at sea level.

High body temperature supports prolonged physical exertion, enabling long-distance migration, complex aerial maneuvers, and extended foraging periods. Endothermy also facilitates advanced parental care—birds incubate eggs and feed altricial young with precision, behaviors difficult for ectotherms to sustain consistently.

However, these advantages come at a cost. High energy demands make birds vulnerable to food shortages. During harsh winters or droughts, mortality rates spike among small songbirds unable to find sufficient calories. Conservation efforts must therefore consider not only habitat protection but also food availability throughout seasons.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Thermoregulation

Several myths persist regarding bird biology and temperature regulation. One common misconception is that birds’ feet freeze in winter. In reality, most birds employ a countercurrent heat exchange system in their legs: warm arterial blood flowing to the feet passes close to cold venous blood returning to the body, minimizing heat loss. As a result, foot temperature remains just above freezing, preventing ice formation while conserving core warmth.

Another myth is that all birds migrate to avoid cold. While many do, numerous species—including cardinals, woodpeckers, and owls—are year-round residents in temperate zones. These birds adapt behaviorally by seeking sheltered roosts, reducing activity, and increasing food intake.

Some believe that feeding birds in winter makes them dependent on humans. Research shows otherwise; supplemental feeding improves winter survival without altering natural foraging instincts. However, proper hygiene and appropriate food types (e.g., black oil sunflower seeds, suet) are essential to prevent disease transmission.

Practical Tips for Observing Endothermic Adaptations in Wild Birds

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, observing thermoregulatory behaviors offers insight into avian endothermy. Here are actionable tips:

- Watch for fluffed plumage: On cold mornings, look for birds appearing “puffy.” This indicates they’re trapping air for insulation.

- Note perching posture: Some birds stand on one leg or tuck their bills under shoulder feathers to minimize heat loss.

- Observe sunning behavior: Even in cold weather, birds may spread wings toward the sun to absorb radiant heat—a supplementary strategy despite being endothermic.

- Use thermal cameras if available: In research settings or wildlife documentaries, infrared imaging reveals heat distribution patterns across the body.

- Monitor feeder activity: Increased visits during cold spells reflect higher caloric demands linked to thermoregulation.

Regional Variability and Climate Change Impacts

While all birds are endothermic, regional adaptations vary. Arctic species like the snowy owl have shorter beaks and limbs to reduce surface area and heat loss (Allen’s Rule). Tropical birds, conversely, often have larger appendages to dissipate excess heat.

Climate change poses new challenges. Warmer average temperatures may reduce heating costs, but increased frequency of extreme weather events—such as polar vortex outbreaks or unseasonal storms—can disrupt energy balance. Shifts in insect emergence timing affect food availability for migratory nestlings, potentially decoupling breeding cycles from peak resource abundance.

Birders and researchers should track local phenology—first sightings, nesting dates, migration arrivals—to detect changes. Citizen science platforms like eBird and Project FeederWatch help compile valuable data on how endothermic animals respond to shifting climates.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds maintain the same body temperature?

- No, while most birds range between 40°C and 42°C, there is slight variation among species. Smaller birds tend to have slightly higher temperatures due to greater surface-area-to-volume ratios.

- Can birds overheat?

- Yes, especially in hot, humid conditions. Birds pant, gular flutter (vibrate throat membranes), and seek shade to cool down since they lack sweat glands.

- How do baby birds stay warm?

- Nestlings rely on parental brooding. Parents sit on the nest to transfer body heat, and altricial chicks often huddle together for shared warmth.

- Are flightless birds still endothermic?

- Yes, penguins and ostriches are fully endothermic. Flightlessness does not affect their ability to regulate internal temperature.

- Is bird endothermy more efficient than in mammals?

- In terms of power-to-weight ratio, yes—avian metabolism supports intense aerobic performance, especially in flight. However, birds require more frequent feeding and are less tolerant of starvation.

In conclusion, birds are unequivocally endothermic organisms whose evolutionary success hinges on precise internal temperature control. From feather structure to metabolic biochemistry, every aspect of their biology supports this vital function. Understanding avian endothermy enriches our appreciation of bird behavior, informs conservation practices, and deepens insights into vertebrate evolution. Whether you're a seasoned ornithologist or a backyard observer, recognizing the signs of thermoregulation enhances every birding experience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4