Yes, birds are vertebrates. This fundamental classification means that birds possess a backbone or spinal column, which is a defining characteristic of all vertebrate animals. A common long-tail keyword variation related to this topic — are birds vertebrates or invertebrates — reflects widespread curiosity about animal classification and the biological traits that distinguish birds from other creatures. The answer is clear: birds belong to the subphylum Vertebrata within the phylum Chordata, placing them in the same broad category as mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Unlike invertebrates such as insects, mollusks, and arachnids, which lack an internal skeleton with a spine, birds have a well-developed bony endoskeleton that includes a rigid vertebral column protecting the spinal cord. This structural framework supports their highly specialized physiology, including flight, efficient respiration, and advanced nervous systems.

Understanding Vertebrates and Invertebrates

To fully appreciate why birds are classified as vertebrates, it’s essential to understand the distinction between vertebrates and invertebrates. Vertebrates are animals with a backbone composed of individual vertebrae that encase and protect the spinal cord. This group makes up only about 3% of all known animal species but includes some of the most familiar animals on Earth — humans, dogs, whales, snakes, frogs, and, of course, birds.

In contrast, invertebrates lack a vertebral column. They represent over 97% of animal species and include diverse organisms such as jellyfish, earthworms, crabs, butterflies, and octopuses. Despite their lack of a backbone, many invertebrates have evolved alternative support structures like exoskeletons (as in insects) or hydrostatic skeletons (as in worms).

Birds not only have a backbone but also exhibit other hallmark features of vertebrates: a closed circulatory system, a centralized brain protected by a skull, bilateral symmetry, and complex organ systems. These traits enable high levels of mobility, sensory perception, and behavioral complexity — all evident in avian life.

Biological Classification of Birds

Birds are members of the class Aves within the kingdom Animalia. All modern birds fall under this taxonomic class, which evolved from theropod dinosaurs during the Mesozoic Era. Fossil evidence, especially from species like Archaeopteryx, shows transitional forms between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds, reinforcing their place in the vertebrate lineage.

The vertebrate status of birds is further confirmed through embryonic development. Like other vertebrates, bird embryos display a notochord during early development — a flexible rod-like structure that eventually becomes surrounded by vertebrae. This developmental trait is one of the key identifiers of chordates, the larger phylum to which vertebrates belong.

Beyond the presence of a spine, birds share additional skeletal features with other vertebrates, including a cranium enclosing the brain, jaws derived from gill arches, and segmented muscles along the body axis. Their bones are lightweight yet strong, often hollow and reinforced internally to withstand the stresses of flight while maintaining structural integrity.

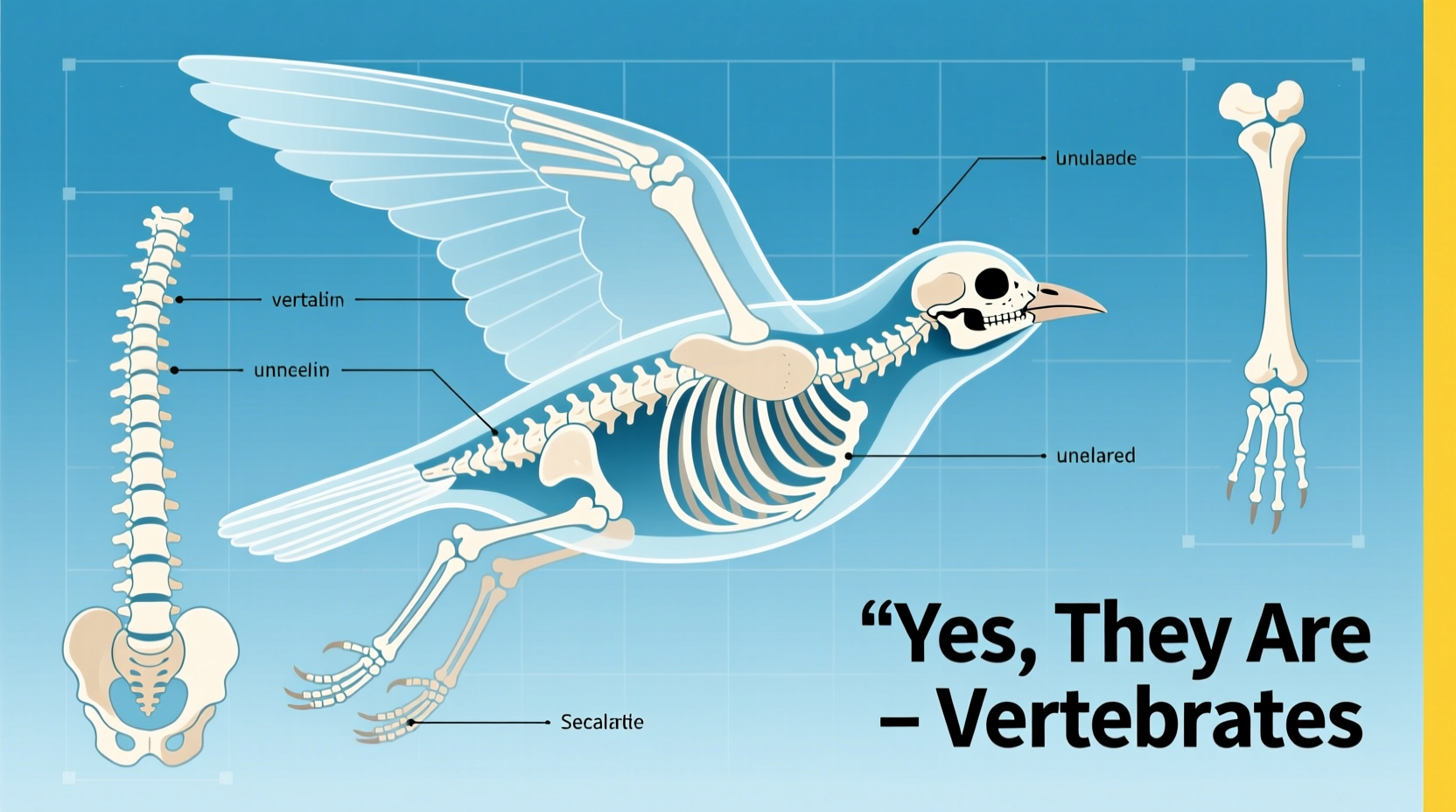

Anatomical Features That Confirm Birds as Vertebrates

The avian skeletal system provides undeniable proof of their vertebrate nature. Let’s examine some key anatomical components:

- Vertebral Column: Birds have a series of interlocking vertebrae running from the base of the skull to the tail. These vertebrae protect the spinal cord and provide attachment points for muscles involved in posture, movement, and flight.

- Skull and Brain Case: The skull houses the brain and major sense organs. It is fused into a rigid structure that protects delicate neural tissues — a feature exclusive to vertebrates.

- Endoskeleton: Birds have an internal bony skeleton made primarily of calcium phosphate. This endoskeleton grows with the animal and allows for muscle attachment, joint articulation, and organ protection.

- Ribs and Sternum: Most birds have ribs connected to thoracic vertebrae and a large keeled sternum (breastbone), which anchors powerful flight muscles. This ribcage functions similarly to those in mammals, offering both protection and respiratory support.

In addition to skeletal traits, birds possess a centralized nervous system with a well-developed brain and spinal cord — another definitive vertebrate characteristic. Their circulatory system features a four-chambered heart (in most species), ensuring efficient separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, much like mammals.

Evolutionary Origins: From Dinosaurs to Modern Birds

One of the most fascinating aspects of bird biology is their evolutionary descent from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs. Paleontologists widely accept that birds are living dinosaurs, specifically avian dinosaurs, while creatures like Tyrannosaurus rex are non-avian dinosaurs.

Fossils from China and Europe have revealed numerous dinosaur species with feathers, wishbones, and three-fingered hands — traits once thought unique to birds. Over millions of years, natural selection favored adaptations such as lighter bones, improved lung efficiency, and enhanced vision, culminating in powered flight.

This evolutionary continuity underscores why birds retain core vertebrate traits. Their ancestors were already vertebrates, and no evolutionary reversal has occurred to eliminate the spine. Instead, the vertebral column adapted to new demands — for example, fusion of certain vertebrae in the lower back (synsacrum) to stabilize the body during flight.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds hold profound symbolic meaning in human cultures worldwide. Their ability to fly — made possible by their lightweight yet robust vertebrate anatomy — has long associated them with freedom, transcendence, and spiritual ascent.

In ancient Egypt, the Ba soul was depicted as a bird with a human head, symbolizing the soul's ability to travel between worlds. In Greek mythology, eagles were linked to Zeus, king of the gods, representing authority and divine vision. Native American traditions often view birds as messengers between humans and the spirit world.

The dove, universally recognized as a symbol of peace, appears in Christian iconography as the Holy Spirit. Meanwhile, ravens feature prominently in Norse and Celtic legends as wise, mysterious beings. These cultural narratives reflect awe at avian capabilities — flight, song, migration — all rooted in their sophisticated vertebrate physiology.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Anatomy

Despite scientific clarity, several misconceptions persist about whether birds are vertebrates. Some people assume that because birds can fly and have hollow bones, they might be more similar to insects or other invertebrates. However, hollow bones do not indicate a lack of a backbone; rather, they are an adaptation for reducing weight without sacrificing strength.

Another myth suggests that birds’ lack of teeth or live birth disqualifies them as “true” vertebrates. But vertebrate classification does not depend on dentition or reproductive mode. Snakes lack limbs, whales live in water, and platypuses lay eggs — yet all are vertebrates. Similarly, birds’ egg-laying reproduction (oviparity) is shared with reptiles and monotremes, not a sign of invertebrate status.

It’s also important to note that being warm-blooded (endothermic) is not a requirement for vertebrate classification. While birds and mammals are endotherms, many vertebrates — including fish, amphibians, and reptiles — are ectothermic. Thermoregulation strategy is separate from skeletal structure.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Researchers

For birdwatchers and field biologists, understanding that birds are vertebrates enhances observational practices. Recognizing their skeletal structure helps explain behaviors such as perching mechanics, flight dynamics, and feeding strategies.

When observing birds, consider how their vertebrate traits influence what you see:

- Posture and Movement: The arrangement of vertebrae affects neck flexibility. Owls, for instance, can rotate their heads nearly 270 degrees due to extra cervical vertebrae — a feature enabled by their vertebrate spine.

- Flight Efficiency: The rigid trunk supported by fused vertebrae allows precise control of wing movements. Watching a hawk soar or a hummingbird hover reveals the biomechanical advantages of a stable internal skeleton.

- Vocalization: Birds produce songs via the syrinx, located at the base of the trachea. This organ is innervated by the nervous system, which travels through the spinal cord — again highlighting their vertebrate organization.

Researchers studying bird migration, cognition, or conservation benefit from knowledge of avian anatomy. For example, tracking devices must account for skeletal load limits, and rehabilitation centers treat fractures in wings and spines just as veterinary clinics do for mammals.

How to Verify Vertebrate Traits in Birds: Tips for Educators and Students

If you're teaching biology or conducting independent study, here are practical ways to confirm that birds are vertebrates:

- Examine X-rays or anatomical diagrams: Medical imaging of birds clearly shows the spinal column, skull, and limb bones. Many educational resources offer labeled avian skeletons.

- Compare with invertebrates: Place a diagram of a bird next to one of an insect or squid. Note the absence of a central backbone in the latter.

- Study museum specimens: Natural history museums often display skeletons of birds alongside other animals, allowing direct comparison.

- Observe behavior: Watch how birds land, walk, or preen — actions requiring coordinated muscle control via a central nervous system and articulated skeleton.

Encourage critical thinking by asking: Could an animal without a spine achieve such coordinated flight? How does bone structure relate to ecological niche? These questions deepen understanding beyond rote memorization.

Regional Differences in Bird Species and Vertebrate Adaptations

Birds inhabit every continent, from Arctic tundras to tropical rainforests. Their vertebrate bodies have adapted remarkably to diverse environments:

| Region | Example Species | Vertebrate Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Antarctica | Emperor Penguin | Dense bones reduce buoyancy for deep diving; countercurrent heat exchange in limbs conserves warmth |

| Amazon Basin | Scarlet Macaw | Strong beak muscles anchored to skull for cracking nuts; zygodactyl feet for climbing |

| Sahara Desert | Ostrich | Powerful leg bones for running up to 45 mph; reduced wing size with vestigial flight function |

| North America | Bald Eagle | Hollow but reinforced bones for flight; keen eyesight processed by large optic lobes in brain |

| Australia | Kookaburra | Robust skull and jaw for consuming prey; territorial vocalizations controlled by syrinx and neural pathways |

These regional examples illustrate how the foundational vertebrate body plan enables survival across extreme conditions — always built upon a bony spine and internal skeleton.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are all birds vertebrates?

- Yes, every known species of bird is a vertebrate. There are no invertebrate birds.

- Do birds have backbones?

- Yes, birds have a well-developed backbone made of individual vertebrae that protect the spinal cord.

- Why do some people think birds are invertebrates?

- Misunderstandings arise due to birds' ability to fly and their lightweight bones, but these are adaptations, not indicators of invertebrate status.

- Is a chicken a vertebrate or invertebrate?

- A chicken is a vertebrate. Like all birds, it has a spine, skull, and internal bony skeleton.

- How are birds different from other vertebrates?

- Birds are distinguished by feathers, toothless beaks, hard-shelled eggs, and most notably, the ability to fly (in most species). However, they still share core vertebrate traits like a backbone and centralized nervous system.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4