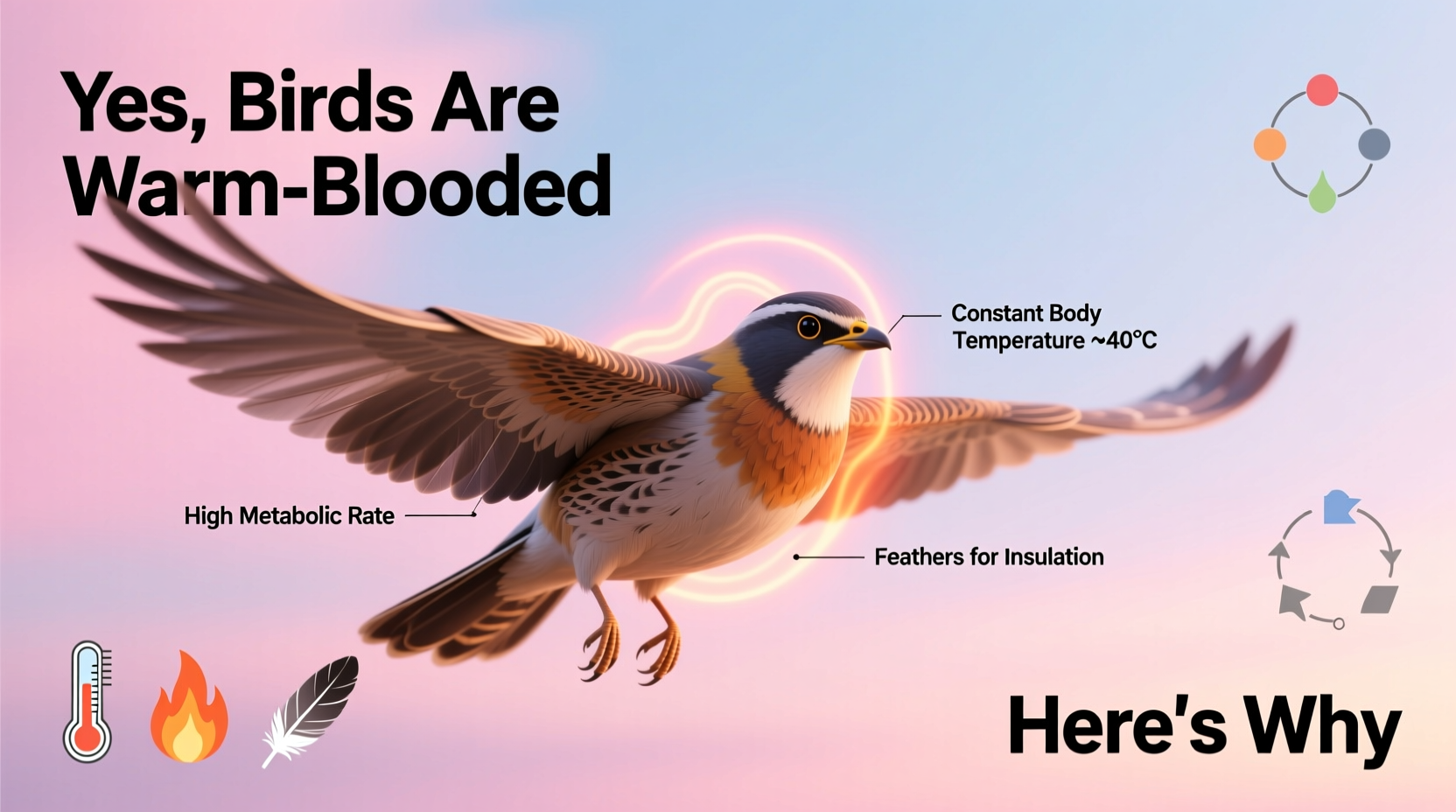

Yes, birds are warm-blooded animals. This means they can regulate their internal body temperature regardless of the external environment—a trait shared with mammals but not with reptiles or amphibians. The scientific term for this is endothermy, and it plays a crucial role in enabling birds to thrive in diverse climates, from Arctic tundras to tropical rainforests. A natural longtail keyword variant like are birds warm blooded animals that maintain constant body temperature captures both the biological fact and the deeper curiosity behind the question: how do birds survive extreme conditions, migrate vast distances, and remain active in cold weather?

The Biology Behind Bird Endothermy

Birds, like mammals, generate heat internally through metabolic processes. Their high metabolic rate allows them to convert food into energy efficiently, producing heat as a byproduct. Most birds maintain a core body temperature between 104°F and 108°F (40°C to 42°C), which is significantly higher than that of humans. This elevated temperature supports rapid muscle contractions needed for flight and keeps physiological systems operating at peak efficiency.

The ability to stay warm-blooded is especially vital during flight, which demands enormous energy output. Feathers, particularly down feathers, provide excellent insulation, trapping air close to the skin and minimizing heat loss. Additionally, birds have a specialized circulatory system called countercurrent heat exchange in their legs. Arteries carrying warm blood from the heart run alongside veins returning cooler blood from the feet, allowing heat to transfer before the blood reaches the extremities. This adaptation prevents excessive heat loss while standing on ice or swimming in cold water.

Evolutionary Origins of Warm-Bloodedness in Birds

Birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, a group that includes well-known species like Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor. Fossil evidence and recent paleontological research suggest that some non-avian dinosaurs may have had elevated metabolic rates, possibly indicating early stages of endothermy. While definitive proof of warm-bloodedness in dinosaurs remains debated, features such as fast growth rates, presence of feathers, and bone structure resembling those of modern birds support the idea that endothermy developed before true birds emerged.

The transition to full endothermy likely provided evolutionary advantages, including increased stamina, faster reaction times, and the ability to exploit new ecological niches. Flight itself may have been a driving force behind the evolution of high metabolism and thermal regulation. Because powered flight requires sustained energy output, only animals capable of generating and retaining large amounts of internal heat could evolve this capability successfully over time.

How Warm-Bloodedness Enables Migration and Survival

One of the most remarkable behaviors enabled by endothermy is long-distance migration. Many bird species travel thousands of miles annually between breeding and wintering grounds, often crossing deserts, oceans, and mountain ranges. These journeys require precise navigation, immense endurance, and the ability to function in rapidly changing temperatures.

For example, the Arctic Tern migrates from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back each year—over 40,000 miles—remaining active throughout despite encountering subzero temperatures and intense solar radiation. Its warm-blooded nature ensures that its nervous system, muscles, and organs continue functioning optimally regardless of ambient temperature.

During cold nights, small birds like chickadees and hummingbirds enter a state of controlled hypothermia called torpor. By temporarily lowering their metabolic rate and body temperature, they conserve energy without losing the benefits of being warm-blooded overall. This flexibility showcases how endothermy isn’t rigid but adaptable based on environmental pressures.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds hold profound symbolic significance across cultures, often linked to their perceived freedom, mobility, and connection to the sky or divine realms. In ancient Egypt, the bau (a bird-headed human) represented the soul’s journey after death. Native American traditions frequently view eagles as messengers between humans and the Creator, symbolizing vision, courage, and spiritual elevation.

In Chinese culture, cranes are symbols of longevity and wisdom, often depicted in art and poetry. Meanwhile, owls in Western mythology are associated with Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, reinforcing the link between birds and higher knowledge. Interestingly, these cultural associations often reflect observable traits made possible by warm-bloodedness—such as alertness, agility, and resilience—all signs of vitality and mental acuity.

This intersection of biology and symbolism reveals why birds continue to captivate human imagination. Their ability to soar above landscapes, endure harsh conditions, and return reliably each season mirrors ideals of perseverance and transcendence—qualities rooted in their physiological makeup.

Practical Tips for Observing Warm-Blooded Adaptations in Birds

If you're interested in observing how birds regulate their temperature in the wild, here are several practical tips for birdwatchers:

- Watch for fluffing behavior: On cold mornings, look for birds puffing up their feathers. This increases trapped air volume and enhances insulation.

- Observe sunbathing postures: Some birds spread their wings or lie on their sides in sunlight to absorb warmth, especially after rainy periods.

- Note shivering and activity levels: Like mammals, birds shiver to generate heat. You might see rapid chest movements in perched birds during freezing weather.

- Look for communal roosting: Species like starlings or sparrows huddle together at night to reduce individual heat loss—an effective strategy among warm-blooded animals.

- Use binoculars and field guides: Identify species known for extreme thermoregulation, such as penguins in Antarctica or ptarmigans in alpine zones.

Timing your observations around dawn and dusk—when birds are most active—can reveal more thermoregulatory behaviors. Early morning hours often show birds warming up after a cold night, while late afternoon may display pre-roosting preparations.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Physiology

A frequent misconception is that because birds lay eggs, they must be cold-blooded like reptiles. However, egg-laying (oviparity) and thermoregulation are independent traits. While most reptiles are ectothermic (relying on external heat sources), birds are endothermic despite sharing the same reproductive method.

Another myth is that all small animals lose heat too quickly to be warm-blooded. In reality, many tiny birds—like the 2-gram bee hummingbird—maintain extremely high metabolic rates to compensate for surface-area-to-volume ratios. They eat up to half their body weight in nectar daily and rely on torpor when food is scarce.

Some people also assume that flightless birds like ostriches or penguins might not be fully warm-blooded. But even flightless species maintain stable internal temperatures. Penguins, for instance, live in some of the coldest environments on Earth and possess thick layers of fat and tightly packed feathers to retain heat—clear adaptations supporting endothermy.

Comparative Table: Warm-Blooded vs. Cold-Blooded Animals

| Feature | Warm-Blooded (Birds & Mammals) | Cold-Blooded (Reptiles, Amphibians, Fish) |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Temperature Regulation | Yes – maintains constant body temperature | No – body temperature fluctuates with environment |

| Metabolic Rate | High – requires frequent feeding | Low – can survive longer without food |

| Energy Source for Heat | Internal metabolism (food conversion) | External environment (sunlight, shade) |

| Insulation Structures | Feathers, fur, fat layers | Scales, moist skin (limited insulation) |

| Activity Level in Cold Weather | Remains high | Decreases significantly |

| Examples | Eagle, robin, sparrow, penguin | Lizard, frog, snake, turtle |

How to Verify Thermoregulatory Traits in Local Bird Species

To deepen your understanding of avian endothermy, consider researching local species using reliable resources:

- Visit university extension websites or ornithology departments for region-specific studies.

- Consult field guides like The Sibley Guide to Birds or apps like Merlin Bird ID, which include behavioral notes relevant to thermoregulation.

- Join citizen science projects such as eBird or Project FeederWatch to contribute data on bird sightings and behaviors tied to seasonal changes.

- Attend workshops hosted by nature centers or Audubon chapters focusing on winter birding and adaptation strategies.

When evaluating online claims about bird physiology, prioritize sources with scientific credentials—peer-reviewed journals, wildlife agencies (e.g., US Fish and Wildlife Service), or academic institutions. Avoid anecdotal blogs or forums lacking citations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are all birds warm-blooded?

Yes, all modern bird species are warm-blooded. This trait is universal across the class Aves and essential for their survival and mobility.

Do birds get cold?

Birds can experience heat loss, especially in wet or windy conditions, but their bodies actively work to maintain core temperature through shivering, fluffing feathers, and seeking shelter.

Can birds freeze to death?

While rare, birds can die from hypothermia if they cannot find enough food to fuel their metabolism or adequate shelter during extreme cold snaps.

Is being warm-blooded necessary for flight?

Powered flight requires high energy output and rapid neuromuscular responses, which are best supported by a stable, high internal temperature—making endothermy highly advantageous, if not strictly required.

How do baby birds stay warm?

Nestlings rely on parental brooding (sitting on the nest) for warmth. Parents transfer heat directly through their brood patch, a featherless area rich in blood vessels on their underside.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4