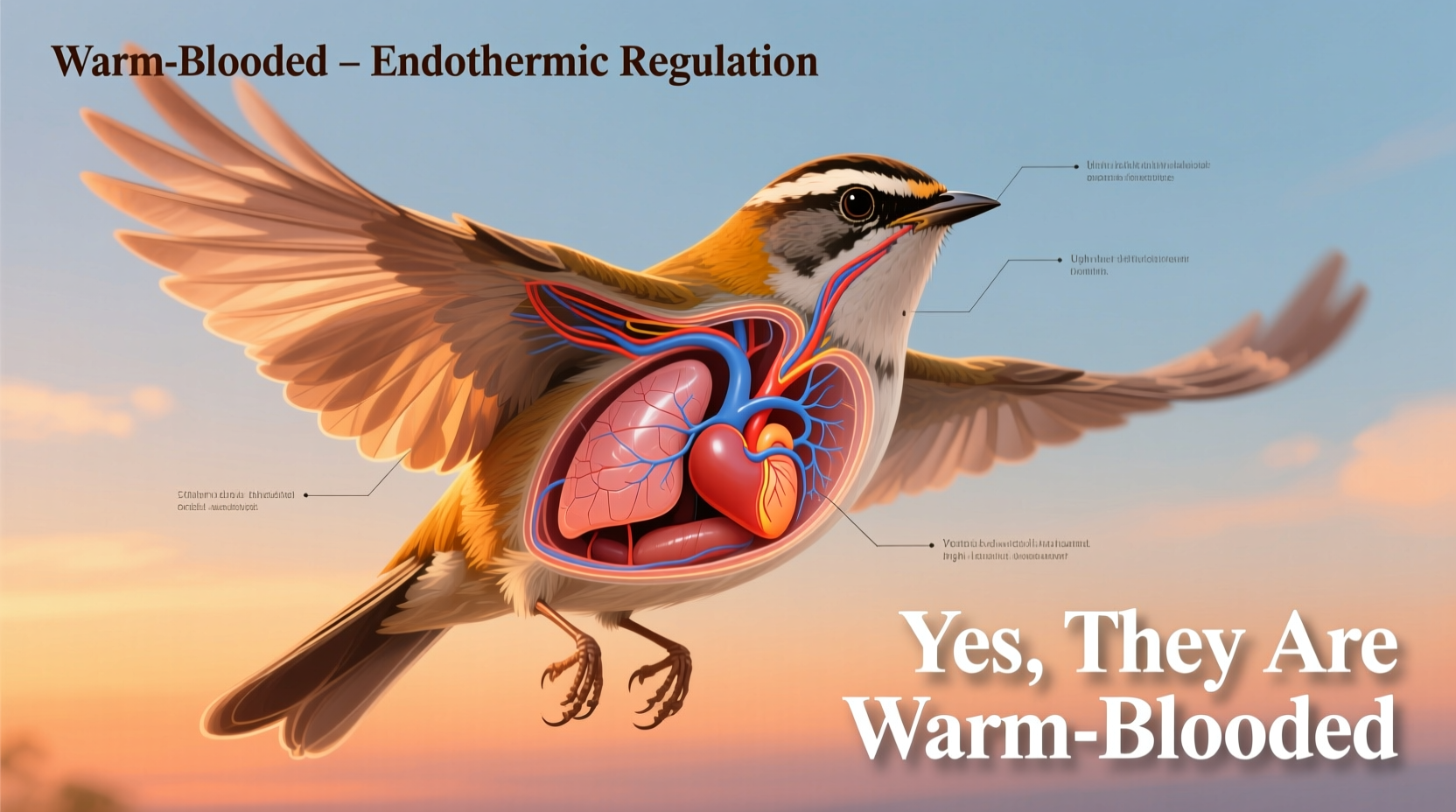

Birds are warm-blooded, meaning they maintain a constant internal body temperature regardless of their environment—a trait shared with mammals. This physiological feature allows them to remain active in cold climates and at high altitudes where cold-blooded animals would become sluggish. The question are birds warm blooded or cold blooded is commonly asked by students, nature enthusiasts, and bird watchers seeking to understand avian biology more deeply. The clear answer is that birds are endothermic, or warm-blooded, which enables them to regulate their metabolism, sustain flight, and inhabit nearly every ecosystem on Earth—from polar regions to tropical rainforests.

The Science Behind Bird Thermoregulation

Warm-bloodedness, scientifically known as endothermy, refers to an organism’s ability to generate and regulate its own body heat. In birds, this process is powered by a high metabolic rate fueled by food consumption. Most birds maintain a core body temperature between 104°F and 108°F (40°C to 42°C), significantly higher than that of humans. This elevated temperature supports rapid muscle contractions needed for flight and quick neurological responses essential for navigation and predator evasion.

To sustain this energy demand, birds consume large amounts of food relative to their body size. For example, a small songbird may eat up to 25% of its body weight daily. Their respiratory and circulatory systems are uniquely adapted to support this high metabolism. Unlike mammals, birds have air sacs that allow for unidirectional airflow through the lungs, ensuring efficient oxygen delivery even during strenuous activity like migration.

How Warm-Bloodedness Affects Bird Behavior and Survival

Being warm-blooded gives birds several evolutionary advantages. One of the most significant is the ability to remain active in cold environments. While reptiles and amphibians slow down or hibernate when temperatures drop, birds can continue foraging, flying, and defending territories year-round. This adaptability explains why species such as the Common Raven and Snowy Owl thrive in Arctic conditions.

Thermoregulation also plays a crucial role in migration. Many birds travel thousands of miles between breeding and wintering grounds, often crossing extreme climates. Their warm-blooded nature allows them to endure freezing temperatures at high altitudes—some geese fly over mountain ranges at elevations exceeding 20,000 feet, where oxygen levels are low and ambient temperatures are far below freezing.

However, maintaining a constant body temperature comes at a cost. Birds must balance heat production with heat loss. Feathers provide excellent insulation, trapping a layer of warm air close to the skin. In cold weather, birds fluff their feathers to increase this insulating layer. Conversely, in hot climates, they pant or hold their wings slightly away from their bodies to release excess heat.

Comparing Warm-Blooded and Cold-Blooded Animals

To better understand what it means for birds to be warm-blooded, it's helpful to compare them with cold-blooded (ectothermic) animals such as reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Ectotherms rely on external sources of heat—like sunlight—to raise their body temperature. As a result, their activity levels fluctuate with environmental conditions. A lizard basking on a rock warms up enough to move quickly, but becomes slow and vulnerable when the sun sets.

In contrast, birds do not depend on external heat sources to function. This independence allows for greater behavioral flexibility. Owls hunt at night in near-freezing temperatures, penguins dive into icy Antarctic waters, and hummingbirds hover in alpine meadows—all thanks to internal thermoregulation.

Despite these differences, some ectotherms exhibit behaviors that mimic warm-bloodedness. For instance, certain pythons coil around their eggs and shiver to generate heat, temporarily raising their body temperature. However, this is a temporary adaptation rather than a sustained physiological state.

Evolutionary Origins of Avian Endothermy

The evolution of warm-bloodedness in birds is closely tied to their dinosaur ancestry. Paleontological evidence suggests that many theropod dinosaurs—close relatives of modern birds—had high growth rates and possibly elevated metabolic rates. Fossilized feathers, bone structure, and isotopic analyses all point toward some degree of endothermy in prehistoric ancestors of today’s birds.

One theory posits that feathers originally evolved for insulation before being co-opted for flight. This implies that thermoregulation may have preceded powered flight in avian evolution. Over millions of years, natural selection favored individuals capable of sustaining higher activity levels, leading to the development of advanced respiratory systems, four-chambered hearts, and efficient circulatory networks—all hallmarks of warm-blooded animals.

Practical Implications for Bird Watchers

Understanding that birds are warm-blooded enhances the experience of bird watching. Observers can interpret behaviors in light of thermoregulatory needs. For example, seeing a bird puffing up its feathers on a winter morning isn’t just cute—it’s a sign of insulation in action. Similarly, birds standing on one leg or tucking their beaks into shoulder feathers are minimizing surface area exposed to cold air.

During summer months, watch for signs of overheating: open-mouthed panting, drooping wings, or reduced activity during peak heat. Providing fresh water in backyard feeders helps birds cool down through evaporation and hydration.

Bird watchers should also consider seasonal variations when planning outings. Migratory species appear at different times depending on climate zones. Knowing that birds regulate their own temperature helps explain why some arrive earlier in spring or linger later into fall, especially as global temperatures shift.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Physiology

Despite scientific consensus, several myths persist about whether birds are warm-blooded or cold-blooded. One common misconception is that because birds lay eggs, they must be cold-blooded like reptiles. However, egg-laying (oviparity) is not linked to thermoregulation. Both birds and monotremes (like the platypus) lay eggs yet are fully warm-blooded.

Another myth is that birds cannot survive in cold climates because they are small. In reality, their high metabolic rate and superior insulation make them remarkably resilient. Chickadees, for instance, can survive nights with temperatures below -30°F by entering a state of controlled hypothermia called torpor, lowering their metabolic rate temporarily while still maintaining core warmth.

Some people confuse feather fluffing with illness. While excessive fluffing can indicate sickness, it’s often a normal response to cold. Context matters: if a bird is alert, eating, and moving normally, fluffed feathers likely reflect thermoregulation, not disease.

Regional Variations and Climate Adaptation

Birds across the globe have adapted their thermoregulatory strategies to local climates. In desert regions, species like the Greater Roadrunner use behavioral adaptations—such as orienting their bodies to minimize sun exposure and using shade—to avoid overheating. They also have specialized nasal glands that excrete salt, reducing the need to lose water through urine.

In contrast, Arctic species like the Emperor Penguin have dense plumage, thick fat layers, and social behaviors (like huddling) to conserve heat. These birds demonstrate how warm-bloodedness works in synergy with physical and social adaptations to ensure survival.

Urban environments present unique challenges. City-dwelling birds face heat islands caused by concrete and asphalt. Studies show that urban robins and sparrows adjust their singing schedules and foraging times to avoid midday heat, illustrating behavioral plasticity within a warm-blooded framework.

| Feature | Warm-Blooded (Birds) | Cold-Blooded (Reptiles) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature Regulation | Internal (endothermic) | External (ectothermic) |

| Average Body Temperature | 104–108°F (40–42°C) | Varies with environment |

| Metabolic Rate | High | Low |

| Insulation | Feathers | Scales |

| Activity in Cold Weather | Active year-round | Limited or dormant |

Tips for Supporting Warm-Blooded Birds in Your Area

- Provide High-Energy Foods: Offer suet, black oil sunflower seeds, and mealworms, especially in winter when birds need extra calories to stay warm.

- Maintain Clean Water Sources: Heated birdbaths prevent freezing and give birds access to drinking and bathing water, critical for feather maintenance and insulation.

- Plant Native Shrubs and Trees: Evergreens like pines and junipers offer shelter from wind and cold, helping birds conserve energy.

- Avoid Pesticides: Chemicals reduce insect populations, depriving birds of vital protein sources needed to fuel their high metabolism.

- Monitor Feeders Regularly: Wet or moldy seed can cause illness. Clean feeders weekly with a mild bleach solution to prevent disease spread.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all birds warm-blooded?

Yes, all modern bird species are warm-blooded. This trait is universal across the class Aves and is essential for flight and environmental adaptability.

Do birds get cold?

Birds can lose body heat, but their physiology prevents them from becoming cold-blooded. They use behavioral and physical strategies—like fluffing feathers and shivering—to stay warm in freezing conditions.

Can birds overheat?

Yes, birds are susceptible to overheating. They cool down by panting, increasing blood flow to unfeathered areas (like legs), and seeking shade during hot weather.

How do baby birds stay warm?

Nestlings rely on parental brooding. Adult birds sit on the eggs and young, transferring body heat. Down feathers in chicks also provide initial insulation.

Is being warm-blooded related to flight?

While not all warm-blooded animals fly, flight requires immense energy and precise muscle control, both supported by a high, stable body temperature. Thus, warm-bloodedness is a prerequisite for sustained avian flight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4