Birds are not mammals, and mammals are not birds—this is a fundamental distinction in biological classification. While both groups are warm-blooded vertebrates, they belong to entirely different classes: Aves for birds and Mammalia for mammals. One common long-tail keyword variant that reflects this query is 'are birds considered mammals or a separate animal class,' and the clear scientific answer is that birds are a separate class of animals, defined by feathers, beaks, egg-laying reproduction, and lack of mammary glands. Understanding whether mammals are birds—or vice versa—helps clarify evolutionary biology, anatomical traits, and ecological roles across species.

Biological Classification: Why Birds and Mammals Are Separate Classes

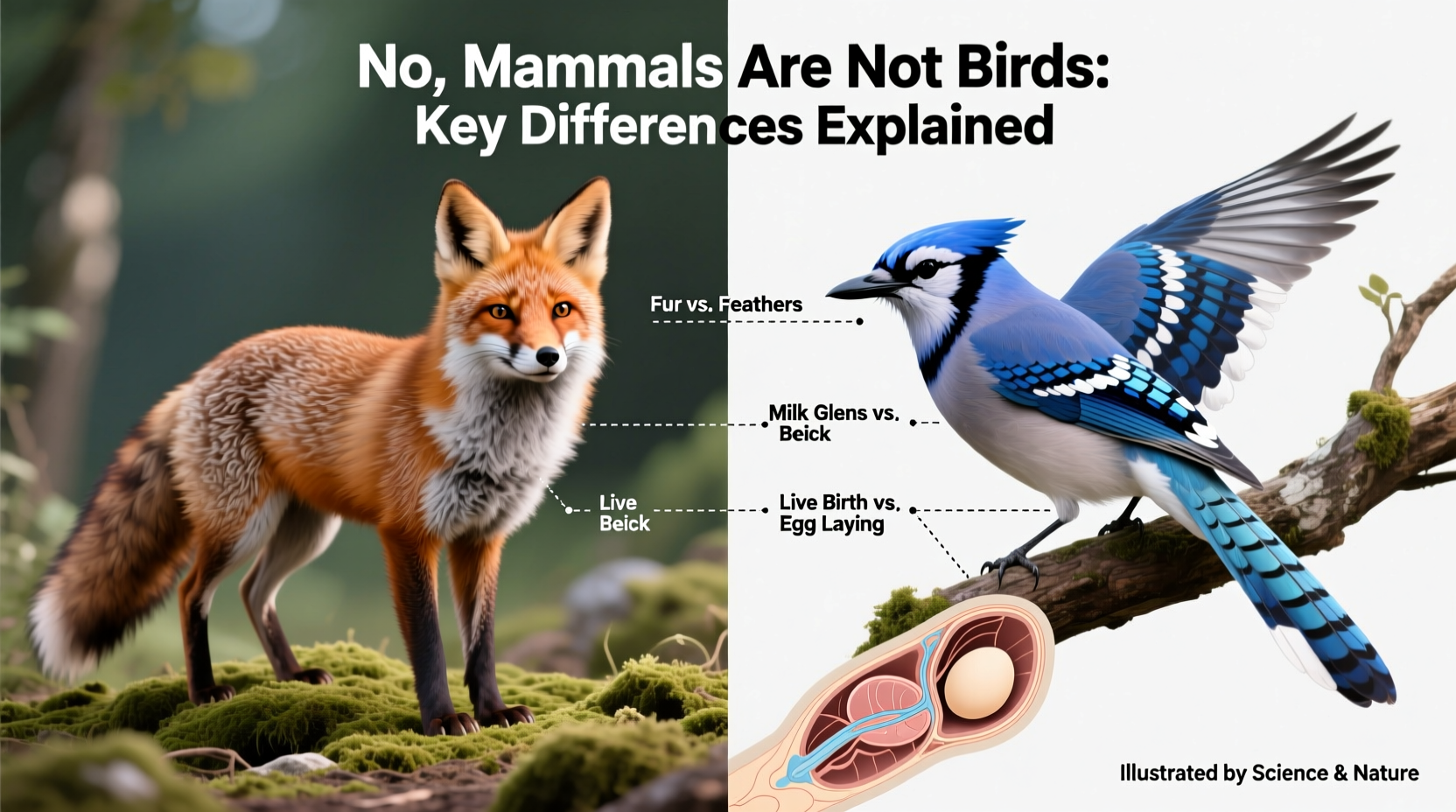

The animal kingdom is organized into taxonomic ranks, including kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Birds belong to the class Aves, while mammals belong to the class Mammalia. This separation is based on key physiological and genetic differences. For example, all mammals produce milk through mammary glands to feed their young—a trait absent in birds. In contrast, birds are the only animals with feathers, which evolved from reptilian ancestors and are critical for flight and thermoregulation.

Another major difference lies in reproduction. Most mammals give birth to live young (with exceptions like the platypus and echidna, which lay eggs), whereas all birds reproduce by laying hard-shelled eggs. Bird eggs are typically laid in nests and incubated until hatching, while mammalian development often occurs internally. These reproductive strategies reflect deep evolutionary divergences dating back over 300 million years.

Anatomical Differences Between Birds and Mammals

Several anatomical features clearly distinguish birds from mammals:

- Feathers vs. Hair/Fur: Feathers are unique to birds and serve multiple functions such as insulation, display, and flight. Mammals have hair or fur, which also provides insulation but lacks aerodynamic capabilities.

- Skeletal Structure: Birds have lightweight, hollow bones adapted for flight. Their skeletons include a fused collarbone (the furcula or “wishbone”) and a keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment. Mammals generally have denser bones suited for terrestrial locomotion.

- Respiratory System: Birds possess a highly efficient one-way airflow respiratory system with air sacs, allowing continuous oxygen supply during flight. Mammals use a tidal breathing system where air moves in and out of the lungs.

- Heart Structure: Both birds and mammals have four-chambered hearts, making them highly efficient at oxygenating blood. However, this similarity results from convergent evolution rather than shared lineage.

Evolutionary Origins: How Birds Diverged from Reptiles, Not Mammals

Despite being warm-blooded like mammals, birds evolved from small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago. Fossils like Archaeopteryx show transitional features between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds, including teeth, long bony tails, and feathered wings. Genetic and fossil evidence confirms that birds are the closest living relatives to extinct dinosaurs—not mammals.

Mammals, on the other hand, evolved from synapsid reptiles much earlier, around 310 million years ago. The split between sauropsids (leading to reptiles and birds) and synapsids (leading to mammals) occurred long before either group developed endothermy (warm-bloodedness). Thus, even though birds and mammals independently evolved similar traits like warm-bloodedness and complex brains, these are examples of convergent evolution, not shared ancestry.

Metabolism and Thermoregulation: Warm-Bloodedness in Birds and Mammals

Both birds and mammals are endothermic, meaning they generate internal heat to maintain a constant body temperature. This allows activity in diverse climates and supports high metabolic rates. However, birds typically have higher body temperatures—ranging from 40°C to 42°C (104°F to 108°F)—compared to most mammals, which average around 37°C (98.6°F).

Birds’ elevated metabolism supports energy-intensive activities like sustained flight. To fuel this, they consume large amounts of food relative to their size and have rapid digestion. Mammals vary widely in metabolic rate depending on size and lifestyle, but none match the per-gram energy output of small passerine birds like hummingbirds.

| Feature | Birds (Class Aves) | Mammals (Class Mammalia) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Covering | Feathers | Hair/Fur |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying (oviparous) | Mostly live birth (viviparous), some egg-laying |

| Milk Production | No | Yes (mammary glands) |

| Teeth | No (have beaks) | Yes (in most species) |

| Bone Density | Lightweight, hollow | Dense, solid |

| Respiratory System | One-way airflow with air sacs | Tidal breathing (in-out) |

| Heart Chambers | Four | Four |

| Warm-Blooded? | Yes | Yes |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds vs. Mammals

Birds hold unique symbolic roles across cultures, often representing freedom, spirituality, or transcendence due to their ability to fly. In ancient Egypt, the ba—a soul aspect—was depicted as a bird with a human head. Native American traditions revere eagles as messengers between humans and the divine. Conversely, mammals like lions, bears, and wolves symbolize strength, protection, and familial bonds.

This cultural divergence reinforces the conceptual separation between birds and mammals. While both appear in myths and heraldry, birds are more frequently associated with celestial realms, whereas mammals are grounded in earthly power and kinship.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Wildlife Enthusiasts

For birdwatchers, understanding that birds are not mammals enhances observational accuracy and appreciation. Key identification cues include:

- Beak shape: Varies by diet (e.g., curved for nectar-feeders, strong and hooked for raptors).

- Flight patterns: Undulating, soaring, or direct flight can help identify species.

- Vocalizations: Bird songs and calls are species-specific and useful for detection in dense habitats.

In contrast, mammal tracking often relies on scat, tracks, and bedding sites. Because birds are diurnal (mostly active during daylight), early morning is the best time for observation. Using binoculars, field guides, and apps like Merlin Bird ID can improve success rates.

It’s also important to recognize that some animals may be mistaken for birds but aren’t. Bats, for instance, are mammals capable of true flight—the only mammals that can. Though they fly, bats lack feathers, give birth to live young, and nurse them with milk, placing them firmly in Mammalia.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Mammals

Several misconceptions contribute to confusion about whether birds are mammals:

- Misconception: All warm-blooded animals are mammals.

Reality: Birds are also warm-blooded but are classified separately. - Misconception: Animals that care for their young must be mammals.

Reality: Many birds exhibit extensive parental care, feeding and protecting chicks for weeks or months. - Misconception: If it flies, it must be a bird.

Reality: Bats (mammals) and insects (arthropods) also fly. - Misconception: Penguins are mammals because they don’t fly and live in cold regions.

Reality: Penguins are flightless birds with feathers, lay eggs, and are excellent swimmers.

How to Teach the Difference: Tips for Educators and Parents

When explaining whether mammals are birds, focus on defining characteristics rather than behavior alone. Use comparative charts, real specimens (like feathers vs. fur samples), and interactive activities. Ask questions like:

- Does it have feathers? → Likely a bird.

- Does it produce milk? → Definitely a mammal.

- Does it lay hard-shelled eggs? → Probably a bird (or reptile).

Encourage children to observe local wildlife and classify backyard visitors. Apps and citizen science projects like eBird or iNaturalist allow families to contribute data while learning taxonomy firsthand.

Scientific Consensus and Ongoing Research

Modern genetics has reinforced the distinction between birds and mammals. Genome studies show significant differences in DNA sequences, chromosome numbers, and gene expression patterns. However, research continues into how similar traits—like vocal learning in parrots and humans—evolved independently.

Some scientists study avian intelligence, finding that crows and parrots rival primates in problem-solving abilities. Yet, despite cognitive similarities, brain structure differs fundamentally: birds lack a neocortex but achieve complex behaviors through densely packed pallial neurons.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are birds reptiles or mammals?

Birds are neither typical reptiles nor mammals. They evolved from reptiles and are now classified in their own class, Aves. - Why do people think birds might be mammals?

Because both are warm-blooded and care for their young, some assume they’re closely related. - Is a bat a bird?

No. Bats are mammals. They give birth to live young and produce milk, despite being able to fly. - Do any birds give live birth?

No. All birds lay eggs. No known bird species gives birth to live young. - What makes a bird a bird?

Feathers, beaks, egg-laying, and lack of teeth define birds biologically.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4