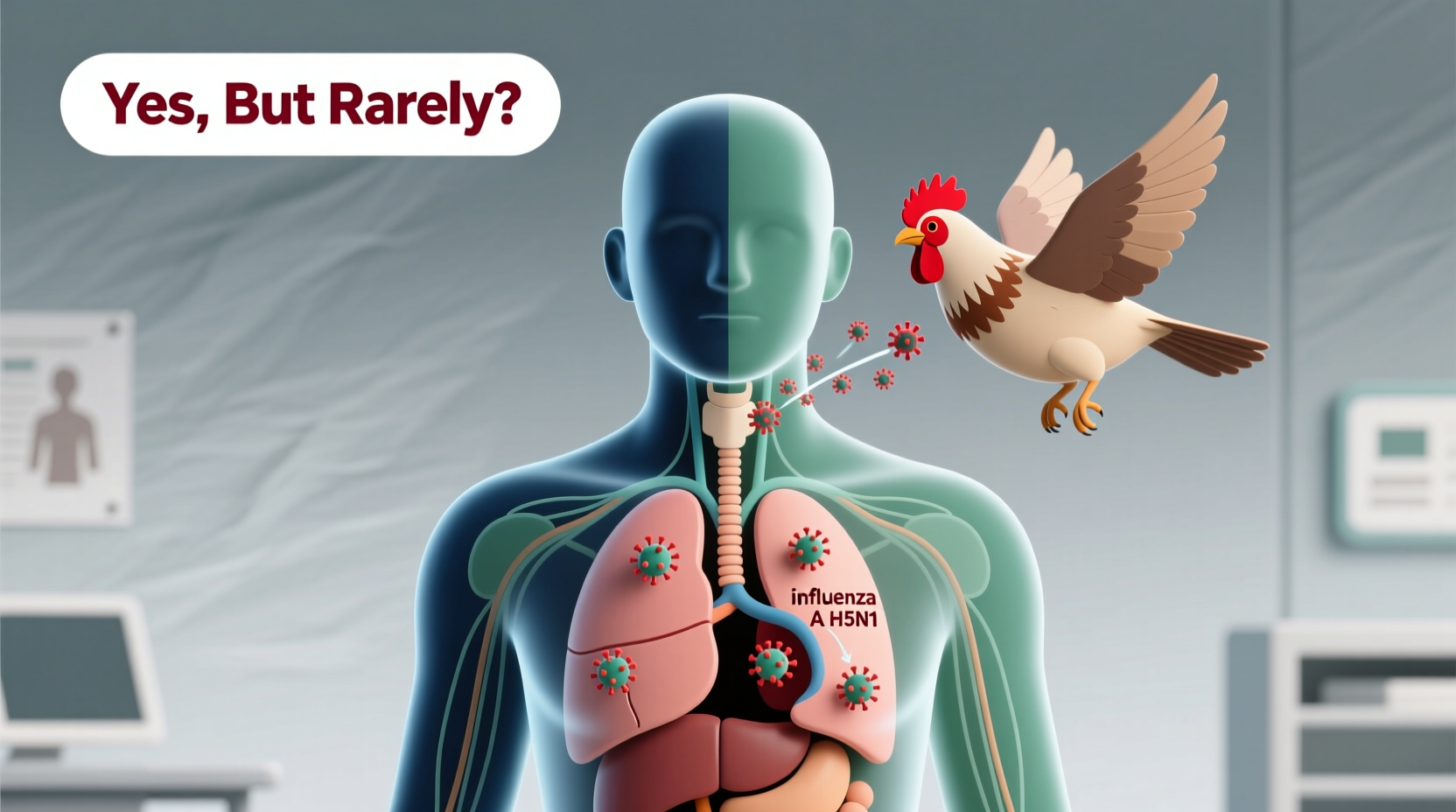

Yes, bird flu can transfer to humans, although such transmission is rare and typically requires close contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments. The avian influenza virus, particularly subtypes like H5N1 and H7N9, has demonstrated the ability to cross the species barrier and cause severe respiratory illness in people. This zoonotic potential makes understanding how bird flu spreads from birds to humans essential for public health, especially for individuals working in agriculture, live bird markets, or wild bird rehabilitation.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Biology

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to a group of influenza A viruses that primarily infect birds. These viruses are naturally found in wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and shorebirds, which often carry the pathogen without showing symptoms. However, when introduced into domestic poultry populations—like chickens, turkeys, and quails—the virus can spread rapidly and cause high mortality rates.

The most concerning subtypes for human health include H5N1, H7N9, and more recently, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which has been circulating globally since 2021. While these strains are highly pathogenic in birds, their ability to infect humans remains limited due to biological barriers in human respiratory cells. Specifically, avian flu viruses bind preferentially to alpha-2,3-linked sialic acid receptors, which are more common in bird intestines and human lower respiratory tracts, making deep lung infection possible but upper airway transmission inefficient.

How Does Bird Flu Spread to Humans?

Transmission of bird flu to humans usually occurs through direct exposure to infected birds or contaminated surfaces. Key routes include:

- Inhalation of aerosolized particles from bird droppings or respiratory secretions

- Direct contact with sick or dead poultry

- Handling raw infected meat without proper protection

- Exposure to contaminated water, feed, or equipment in farms or live markets

There is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission of bird flu, which limits pandemic risk. However, sporadic cases have occurred, particularly in Asia, where backyard farming and live animal markets increase human-bird interaction. For example, during the 2003–2006 H5N1 outbreaks in Southeast Asia, over 600 human cases were reported, with a fatality rate exceeding 60%. More recent cases linked to H5N1 in the U.S. in 2022 involved a dairy worker exposed to infected cattle, marking the first known instance of possible mammal-mediated transmission.

Human Symptoms and Health Risks

When bird flu does infect humans, it tends to cause severe disease. Symptoms may appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure and can progress rapidly. Common signs include:

- Fever and chills

- Cough and sore throat

- Muscle aches and fatigue

- Shortness of breath or pneumonia

- In severe cases, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and death

Unlike seasonal flu, bird flu often leads to lower respiratory tract infections, making early diagnosis critical. Laboratory testing via RT-PCR on respiratory samples is required for confirmation. Prompt antiviral treatment with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir can improve outcomes, especially if administered within 48 hours of symptom onset.

Global Outbreaks and Surveillance Efforts

Bird flu is not new, but its geographic reach and host range have expanded significantly in recent decades. The first known human case of H5N1 was recorded in Hong Kong in 1997. Since then, outbreaks have occurred across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. In 2022, the United States experienced its largest-ever avian flu outbreak, affecting over 58 million birds across 46 states.

Wild bird migration plays a major role in spreading the virus across continents. Infected migratory birds can introduce the virus to new regions, where it spills over into commercial and backyard flocks. International surveillance networks, including the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and the CDC, monitor outbreaks and issue alerts to prevent further spread.

| Virus Subtype | First Human Case | Case Fatality Rate | Geographic Spread |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1997 (Hong Kong) | ~60% | Asia, Africa, Europe, Middle East |

| H7N9 | 2013 (China) | ~40% | Mainland China |

| H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b | 2021 (global) | Data pending | Global (including Americas) |

Prevention and Safety Measures for At-Risk Individuals

While the general public faces low risk, certain groups should take precautions to reduce exposure. These include poultry farmers, veterinarians, wildlife biologists, and bird handlers. Recommended safety practices include:

- Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, and goggles when handling birds

- Avoiding contact with sick or dead wild birds

- Practicing strict hand hygiene after any bird interaction

- Reporting unusual bird deaths to local authorities or wildlife agencies

- Ensuring poultry is cooked to an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C)

Backyard flock owners should isolate new birds, control rodent populations, and limit visitors to reduce biosecurity risks. Commercial farms may implement vaccination programs in some countries, though this is not universally adopted due to concerns about masking infection and hindering surveillance.

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—from messengers of the divine to omens of change. In many traditions, birds represent freedom, spirituality, and connection between earth and sky. However, during disease outbreaks, these perceptions can shift dramatically. Culling millions of birds to contain avian flu can lead to emotional and economic distress, particularly in rural communities where poultry is both livelihood and sustenance.

In parts of Southeast Asia, ritual slaughter and temple offerings involving live birds have raised concerns about amplifying transmission risks. Public health campaigns must balance cultural sensitivity with urgent disease control measures. Education efforts that incorporate local beliefs and community leaders tend to be more effective than top-down mandates.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about bird flu and its threat to humans:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized egg products are safe. The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: There is no evidence of efficient or sustained human-to-human transmission. - Myth: Only wild birds carry the virus.

Fact: Domestic poultry are more likely to experience deadly outbreaks and serve as bridges to human exposure.

What Travelers and Birdwatchers Should Know

For birdwatchers and ecotourists, the risk of contracting bird flu remains extremely low. However, responsible practices are crucial to protect both human health and bird populations. Tips include:

- Maintaining a safe distance from wild birds, especially waterfowl and shorebirds

- Using binoculars instead of approaching nests or roosting sites

- Disinfecting boots, gear, and vehicle tires after visiting wetlands or farms

- Checking government advisories before traveling to areas with active outbreaks

- Avoiding participation in bird feeding or handling activities in affected regions

National parks and wildlife refuges may temporarily close certain areas during outbreaks to minimize disturbance and reduce transmission risks. Always verify access status through official websites or visitor centers.

Future Outlook and Pandemic Preparedness

The ongoing evolution of avian influenza viruses raises concerns about future pandemics. If a strain acquires mutations that allow efficient human-to-human transmission, global health systems could face significant challenges. Scientists monitor viral changes closely, particularly in the hemagglutinin (HA) and polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2) genes, which influence host specificity and virulence.

Vaccine development is underway, with candidate vaccines for H5 and H7 subtypes stockpiled in some countries. However, producing a matched vaccine takes time, underscoring the importance of early detection and containment. Strengthening One Health approaches—integrating human, animal, and environmental health—is vital for preventing spillover events.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can you get bird flu from eating chicken?

- No, you cannot get bird flu from eating properly cooked chicken or eggs. The virus is killed at temperatures above 165°F (74°C).

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There is no widely available commercial vaccine for the general public, but experimental vaccines exist for high-risk groups and are part of pandemic preparedness plans.

- Have there been recent cases of bird flu in humans?

- Yes, isolated cases occur annually, mostly in Asia. In 2022, one case was confirmed in the U.S. in a person exposed to infected dairy cattle.

- Can pets get bird flu?

- Rarely, but cats and other mammals have tested positive after consuming infected birds. Keep pets away from sick or dead wildlife.

- How is bird flu different from seasonal flu?

- Bird flu is caused by avian-specific influenza strains, affects birds primarily, and causes more severe disease in humans compared to seasonal flu, which circulates annually among people.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4