Yes, birds can fly—most of them, at least. The vast majority of bird species are fully capable of powered, sustained flight, a defining characteristic that sets them apart in the animal kingdom. When we ask can birds fly, the answer is a resounding yes for over 10,000 species worldwide. Flight enables birds to migrate across continents, escape predators, find food, and access remote nesting sites. While there are notable exceptions like ostriches, penguins, and kiwis, the ability to fly remains one of the most remarkable evolutionary adaptations in nature. This article explores the biological mechanisms behind avian flight, identifies flightless birds and why they evolved that way, offers practical tips for observing flying birds in the wild, and dispels common misconceptions about bird mobility.

The Biology Behind Bird Flight: How Do Birds Fly?

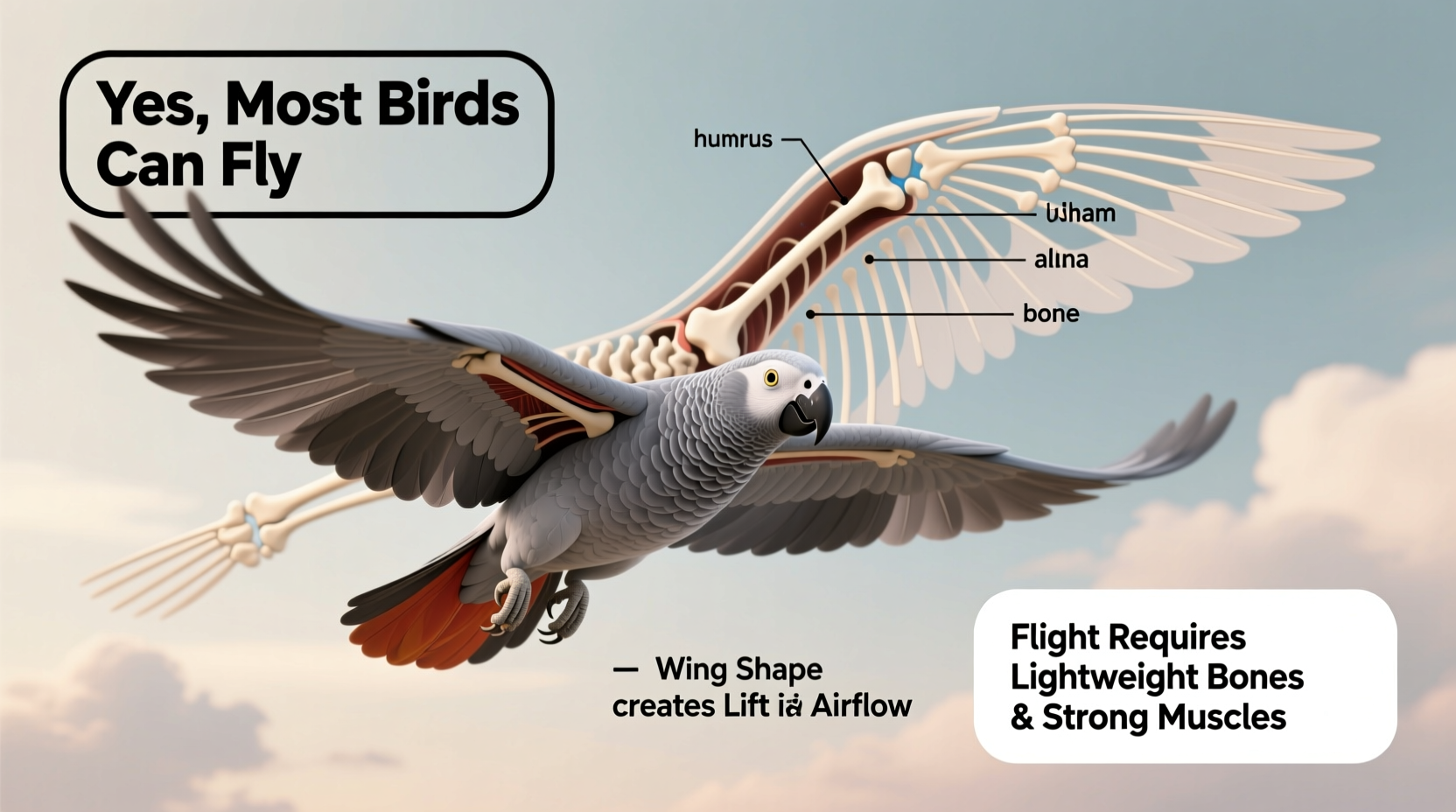

Birds achieve flight through a combination of specialized anatomical features, lightweight bodies, and powerful musculature. Unlike mammals or reptiles, birds have evolved several key adaptations that make aerial locomotion not only possible but highly efficient.

Skeletal Structure and Lightweight Bones

One of the most critical components enabling flight is the bird’s skeletal system. Bird bones are both strong and remarkably light. Many are hollow with internal struts for reinforcement—a design known as pneumatization. These air-filled bones reduce overall body weight without sacrificing structural integrity, allowing birds to generate lift more easily.

Wings and Feather Design

Bird wings are modified forelimbs covered in flight feathers (remiges) that provide the necessary surface area and shape for generating lift and thrust. The asymmetrical vane of primary feathers helps create an airfoil shape, similar to an airplane wing, where airflow moves faster over the top than underneath, producing upward force.

Contour feathers streamline the body, reducing drag during flight, while down feathers insulate. The precise arrangement and interlocking mechanism of barbules and hooks keep feathers tightly aligned, essential for maintaining aerodynamic efficiency.

Muscular Power: The Role of the Pectorals

The pectoralis major muscle powers the downstroke—the main source of lift and propulsion. In many flying birds, this single muscle can make up 15–25% of their total body mass. A secondary muscle, the supracoracoideus, lifts the wing during the recovery stroke via a pulley-like tendon system beneath the shoulder joint. This dual-muscle setup allows for rapid, controlled flapping essential for takeoff, hovering, and maneuvering.

Respiratory and Circulatory Efficiency

Flight demands high energy output, requiring efficient oxygen delivery. Birds possess a unique respiratory system with rigid lungs connected to air sacs distributed throughout their body and even into some bones. This unidirectional airflow ensures constant oxygen supply during both inhalation and exhalation, supporting sustained aerobic activity.

Their four-chambered heart also delivers oxygen-rich blood rapidly, maintaining high metabolic rates needed for endurance flight. Some migratory species, like the Arctic Tern, rely on this system to fly over 40,000 miles annually between poles.

Which Birds Cannot Fly? Understanding Flightlessness

While flight is widespread among birds, around 60 extant species are completely flightless. These include well-known examples such as:

- Ostrich (Struthio camelus)

- Penguin (Spheniscidae family)

- Kiwi (Apteryx spp.)

- Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

- Cassowary (Casuarius spp.)

- Takahe (Porphyrio hochstetteri)

These birds lost the ability to fly due to evolutionary pressures in environments where flight was unnecessary or disadvantageous. Often isolated on islands with few predators, such as New Zealand (home to kiwis and takahes), flight became energetically costly and less beneficial. Over time, natural selection favored traits like larger size, stronger legs for running or swimming, and reduced wing structures.

| Flightless Bird | Habitat | Max Speed (if applicable) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich | African savannas | 45 mph (72 km/h) | Largest living bird; uses wings for balance and display |

| Penguin | Antarctic and southern oceans | Swims up to 22 mph (35 km/h) | Wings adapted into flippers for underwater 'flight' |

| Kiwi | New Zealand forests | N/A (slow walker) | Nocturnal; tiny vestigial wings under fur-like feathers |

| Emu | Australian plains | 31 mph (50 km/h) | Second-tallest bird; wings nearly useless |

| Cassowary | Tropical rainforests of New Guinea/Australia | 30 mph (48 km/h) | Extremely dangerous if provoked; dagger-like claws |

Evolutionary Trade-offs: Why Lose Flight?

Flightlessness evolves when the costs of maintaining flight capability outweigh the benefits. Energy required to build and power flight muscles, maintain large sternums (keels), and carry robust wing bones can be redirected toward other survival strategies.

For example, ostriches evolved long, powerful legs for sprinting across open terrain—far more effective than flight in escaping lions or cheetahs. Penguins traded aerial agility for hydrodynamic form, becoming expert divers that ‘fly’ through water instead. Kiwis, nocturnal and ground-dwelling, invested in enhanced olfactory senses rather than flight.

However, flightless birds are especially vulnerable to introduced predators (like rats, cats, and dogs), which explains why many face extinction threats today. Conservation efforts often focus on predator-free sanctuaries and breeding programs.

Observing Bird Flight: Tips for Birdwatchers

Watching birds in flight is one of the most rewarding aspects of birding. Whether you're tracking raptors soaring on thermals or flocks of shorebirds performing synchronized aerial displays, understanding flight behavior enhances your experience.

Best Times and Locations to Observe Flying Birds

- Dawn and Dusk: Many birds are most active during early morning and late afternoon, making these ideal times for spotting migratory species or songbirds commuting to roosts.

- Coastal Cliffs and Mountain Ridges: Raptors like eagles and hawks use updrafts along elevated terrain to glide effortlessly. Hawk watches are popular at sites like Cape May (NJ) or Glacier National Park (MT).

- Wetlands and Lakeshores: Waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swans frequently take off and land on water, offering clear views of wingbeats and formation flying.

- Open Fields and Grasslands: Look for swallows, swifts, and nighthawks performing acrobatic maneuvers while feeding on insects mid-air.

What to Bring

- Binoculars (8x42 or 10x42 recommended)

- Field guide or birding app (e.g., Merlin Bird ID)

- Notebook or voice recorder for logging behaviors

- Camera with zoom lens (optional)

Key Flight Behaviors to Identify Species

Bird flight patterns can help identify species even at great distances:

- V-formation: Common in geese and ibises; reduces wind resistance and conserves energy.

- Bounding flight: Small birds like woodpeckers alternate flaps with tucked-wing glides.

- Soaring with flat wings: Turkey Vultures tilt slightly in a dihedral angle; distinguishes them from hawks.

- Rapid wingbeats: Hummingbirds hover with up to 80 beats per second.

- Erratic zig-zagging: Swallows and swifts chase flying insects with incredible agility.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flight

Despite widespread fascination, several myths persist about whether and how birds fly:

Myth: All Birds Can Fly

False. As discussed, dozens of species lack functional flight. Even among flying birds, juveniles may not fly immediately after fledging, and injured or molting individuals may temporarily lose flight ability.

Myth: Bats Are Birds Because They Fly

No. Bats are mammals. Birds are defined by feathers, toothless beaks, hard-shelled eggs, and specific skeletal features. Flight evolved independently in bats, birds, and insects.

Myth: Larger Birds Can’t Fly Long Distances

Incorrect. Some of the longest migrations belong to large birds. The Bar-tailed Godwit flies nonstop for over 7,000 miles from Alaska to New Zealand. The Wandering Albatross soars thousands of miles across oceans using dynamic soaring techniques.

Myth: Flightless Birds Are Primitive

This is outdated thinking. Flightlessness is a derived trait—not a sign of evolutionary backwardness. It reflects adaptation to specific ecological niches.

Human Impact on Bird Flight and Mobility

Urban development, climate change, and pollution increasingly affect bird flight patterns and capabilities.

- Light Pollution: Disorients nocturnal migrants, leading to fatal collisions with buildings.

- Wind Turbines: Pose collision risks, especially for raptors and bats. Proper siting and radar systems can mitigate impacts.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Reduces connectivity between feeding and nesting areas, forcing birds to fly longer or riskier routes.

- Climate Shifts: Alter migration timing; some species now arrive before food sources emerge.

Bird-friendly architecture, protected flyways, and citizen science projects like eBird help monitor and preserve avian flight behaviors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can all birds fly?

- No, not all birds can fly. Approximately 60 species, including ostriches, penguins, and kiwis, are flightless due to evolutionary adaptations.

- Why can birds fly but humans can't?

- Birds have lightweight skeletons, powerful flight muscles, specialized wings, and efficient respiratory systems—all evolved specifically for flight. Humans lack these biological adaptations.

- Do baby birds fly right away?

- No. Young birds typically fledge (leave the nest) before they can fly proficiently. They practice short flights and are fed by parents until fully capable.

- How do birds fly without getting tired?

- Many birds use energy-saving techniques like thermal soaring, tailwinds, and V-formations. Their highly efficient metabolism and respiratory system also support endurance.

- Can injured birds regain the ability to fly?

- Sometimes. With proper rehabilitation, birds that suffered broken wings or feather damage may recover flight ability. However, severe injuries to muscles or bones can result in permanent disability.

In conclusion, the question can birds fly has a nuanced but clear answer: yes, the overwhelming majority of bird species are built for and capable of flight. From the tiniest hummingbird to the mighty albatross, avian flight represents one of nature’s most elegant solutions to movement and survival. By understanding the science behind it, recognizing exceptions, and protecting habitats, we ensure that future generations can continue to marvel at birds in flight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4