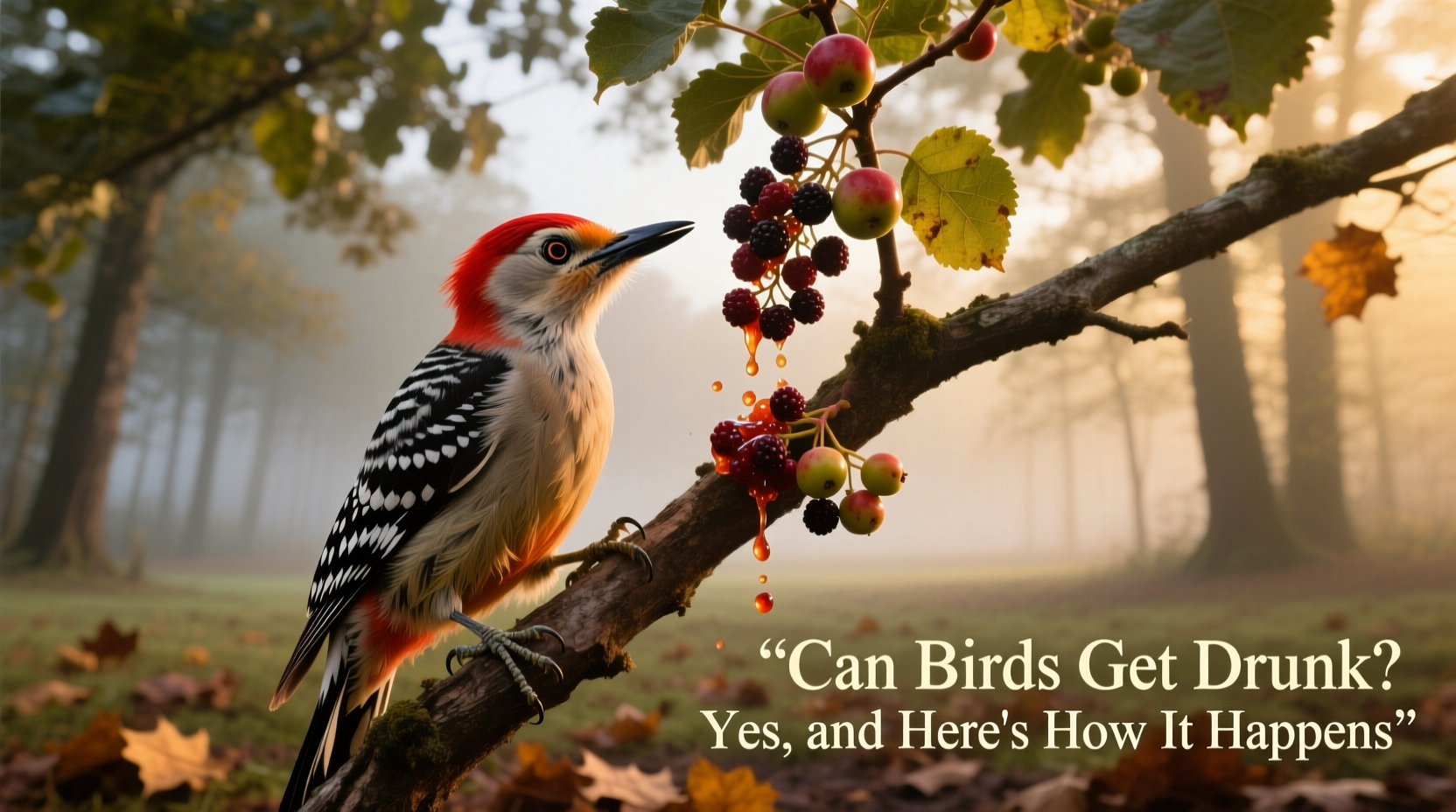

Yes, birds can get drunk—especially when they consume overripe or fermented fruits containing ethanol. This natural phenomenon, often referred to as avian alcohol intoxication, occurs when birds ingest fermenting berries or fruits that have begun to break down due to yeast activity. While not common in all species, certain fruit-eating birds like waxwings, starlings, and robins are more prone to accidental alcohol consumption during late autumn and winter months. These seasonal patterns align with the availability of fermenting fruits on trees and shrubs, making can birds get drunk from eating fruit a frequently searched query among birdwatchers and wildlife enthusiasts.

How Do Birds End Up Consuming Alcohol?

Birds don’t seek out alcohol the way humans do. Instead, intoxication typically results from natural fermentation processes in fruits left on trees or fallen to the ground. When sugars in fruits such as apples, mountain ash berries, hawthorns, or juniper berries ferment due to exposure to wild yeast (like Saccharomyces cerevisiae), ethanol is produced. In cold climates, especially after frost sets in, this fermentation accelerates, increasing ethanol concentration.

Fruit-eating birds, particularly those adapted for quick digestion of sugary foods, may not distinguish between fresh and fermented fruit. Their short digestive tracts allow rapid processing, but also mean alcohol enters the bloodstream quickly. Because birds metabolize alcohol differently than mammals—and generally lack sufficient levels of the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH)—even small amounts can lead to noticeable impairment.

Biological Effects of Alcohol on Birds

Alcohol affects avian physiology in ways similar to its impact on humans, though the consequences are often more severe due to size and metabolic differences. Ethanol acts as a central nervous system depressant, leading to:

- Loss of coordination (ataxia)

- Slurred flight or inability to fly

- Disorientation and poor judgment

- Reduced predator avoidance

- In extreme cases, respiratory depression, coma, or death

Studies have shown that blood ethanol concentrations as low as 0.5% can impair flight control in passerine birds. Unlike humans, birds cannot sweat or pant effectively to cool down or expel toxins, so their bodies struggle to eliminate alcohol efficiently. Additionally, their high metabolic rate means toxins circulate faster through vital organs.

A well-documented case involved Bohemian waxwings (Bombycilla garrulus) found intoxicated beneath rowan trees in northern Europe after feeding on fermented berries. Some were unable to fly, while others collided with windows or walked erratically on the ground—behaviors consistent with birds acting drunk after eating fermented fruit.

Species Most Likely to Experience Alcohol Intoxication

Not all birds are equally susceptible. The likelihood depends on diet, habitat, and seasonal food availability. The most commonly reported species include:

| Species | Diet Type | Common Locations | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemian Waxwing | Fruit specialist | Northern Europe, Canada, Alaska | High |

| European Starling | Omnivorous, eats fruit | Europe, North America | Moderate |

| American Robin | Worms & berries | North America | Moderate |

| Cedar Waxwing | Fruit-dependent | Eastern & Central U.S. | High |

| Blackbird (Turdus merula) | Berries & insects | UK, Western Europe | Moderate |

These species often travel in flocks and descend en masse on fruit-bearing trees, increasing the chance of collective intoxication. Observations of large groups of waxwings stumbling or flying into objects after feeding support anecdotal evidence of widespread drunken bird behavior in winter months.

Seasonal Patterns and Environmental Triggers

Alcohol-related incidents in birds are strongly seasonal. Late fall and early winter (October to January in the Northern Hemisphere) are peak times for such events. This timing coincides with:

- Fruit ripening and decay cycles

- Cold weather promoting fermentation

- Migratory movements into urban or suburban areas where ornamental fruit trees are abundant

- Reduced availability of alternative food sources

In cities, planted ornamental trees like cotoneaster, pyracantha, and crabapple increase exposure risk. These non-native plants retain fruit longer into winter, providing a continuous supply of fermenting material. Urban environments may therefore see higher rates of intoxicated birds compared to rural zones.

Myths and Misconceptions About Drunk Birds

Several myths persist about birds and alcohol. One common misconception is that birds “enjoy” being drunk or seek out fermented fruit for pleasure. There is no scientific evidence supporting intentional intoxication. Birds rely heavily on visual and olfactory cues to find food, and fermentation doesn’t always alter appearance or smell enough to deter them.

Another myth is that giving milk or water to an intoxicated bird helps sober it up. In reality, forcing fluids can be dangerous. The best course of action is to protect the bird from predators and traffic and allow time for natural recovery.

Some believe that only wild birds are affected, but captive birds can also become intoxicated if fed spoiled fruit. Pet owners should avoid offering overripe produce to parrots, toucans, or other frugivores.

What Should You Do If You Find a Drunk Bird?

If you encounter a bird exhibiting signs of intoxication—such as slurred movement, inability to fly, or unresponsiveness—it’s important to act responsibly:

- Assess safety: Move the bird to a quiet, sheltered area away from roads, pets, and people.

- Do not feed or give liquids: Avoid offering food, water, or milk, which could cause aspiration or digestive distress.

- Provide warmth: Place the bird in a ventilated box with soft bedding and a heat source (like a warm towel).

- Allow rest: Most birds recover within a few hours once ethanol is metabolized.

- Contact a wildlife rehabilitator: If the bird shows no improvement after several hours, or has visible injuries, professional help may be needed.

Never attempt to administer antidotes or stimulants. Human medications can be toxic to birds.

Can Birds Die From Alcohol Poisoning?

Yes, fatal alcohol poisoning in birds is possible, though relatively rare. Mortality usually results from secondary causes rather than direct toxicity. For example:

- Predation: Impaired birds are easy targets for cats, hawks, or owls.

- Trauma: Flying into windows, vehicles, or power lines increases accident risk.

- Exposure: Hypothermia can occur if a bird cannot reach shelter.

- Starvation: Disorientation may prevent normal foraging.

In laboratory settings, lethal doses (LD50) of ethanol for small birds range between 5–7 g/kg body weight. However, field observations suggest behavioral changes occur at much lower levels—sometimes below 1 g/kg.

Comparative Physiology: Birds vs. Mammals

Understanding why birds are more vulnerable requires comparing their biology to mammals. Key differences include:

- Liver function: Birds produce less alcohol dehydrogenase, slowing ethanol breakdown.

- Body mass: Smaller size means lower total body fluid volume, concentrating alcohol effects.

- Respiratory system: High oxygen demands make CNS depression more dangerous.

- Thermoregulation: Birds cannot shiver or sweat effectively under sedation, risking hypothermia.

This makes even mild intoxication potentially life-threatening, especially in cold weather. Unlike humans who might experience euphoria at low blood alcohol levels, birds show primarily motor deficits and stress responses.

Observational Tips for Birdwatchers

If you're a birder, recognizing signs of intoxication can improve your field identification skills and aid conservation efforts. Look for:

- Erratic flight paths or sudden drops mid-air

- Birds walking instead of flying when startled

- Unusual tameness or lack of fear toward humans

- Flocks congregating heavily around specific fruiting trees

- Vocalizations that sound slurred or irregular

Report unusual clusters of impaired birds to local wildlife authorities or citizen science platforms like eBird. Geotagged observations help track seasonal trends in how birds get drunk from natural sources.

Prevention and Responsible Gardening

While we can't control natural fermentation, there are steps to reduce risks in human-managed landscapes:

- Rake up fallen fruit beneath trees regularly in autumn and winter.

- Choose non-fruiting cultivars of ornamental trees if birds frequently appear impaired nearby.

- Avoid placing bird feeders near decaying fruit piles.

- Educate neighbors about the dangers of fermented fruit for wildlife.

Community awareness plays a key role in minimizing unintentional harm. Even small actions can prevent multiple birds from becoming intoxicated during critical survival periods.

Scientific Research and Future Directions

Despite anecdotal reports, formal studies on avian ethanol metabolism remain limited. Recent research using breathalyzer-like devices on captured birds has confirmed measurable ethanol levels post-feeding on fermented fruit. Scientists are exploring whether some populations develop tolerance or behavioral adaptations to avoid spoiled food.

Long-term monitoring could reveal evolutionary implications—if chronic exposure leads to selection against certain feeding behaviors or influences migration timing. Understanding whether birds can build tolerance to alcohol remains an open question in avian ecology.

FAQs About Birds and Alcohol

- Can pet birds get drunk?

- Yes, if fed overripe or fermented fruit. Always provide fresh produce and remove uneaten food within a few hours.

- Is it safe to leave fruit out for birds in winter?

- Fresh fruit is fine, but remove any pieces that begin to rot or ferment within 24 hours.

- Do birds know when fruit is fermented?

- Not reliably. Visual cues dominate their foraging; fermented fruit may still look appealing.

- How long does it take for a bird to sober up?

- Typically 2–6 hours, depending on species, dose, and temperature.

- Should I call a vet if I find a drunk bird?

- If it’s in immediate danger or hasn’t recovered after four hours, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator.

In conclusion, yes, birds can get drunk—not by choice, but as an unintended consequence of their natural diet. From waxwings to starlings, many species face real risks when consuming fermented fruits, especially in colder months. By understanding the biological mechanisms, recognizing symptoms, and taking preventive measures, both birders and the public can help minimize harm. Whether you’re asking can birds get drunk from berries out of curiosity or concern, the answer underscores the delicate balance between nature’s processes and animal survival.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4