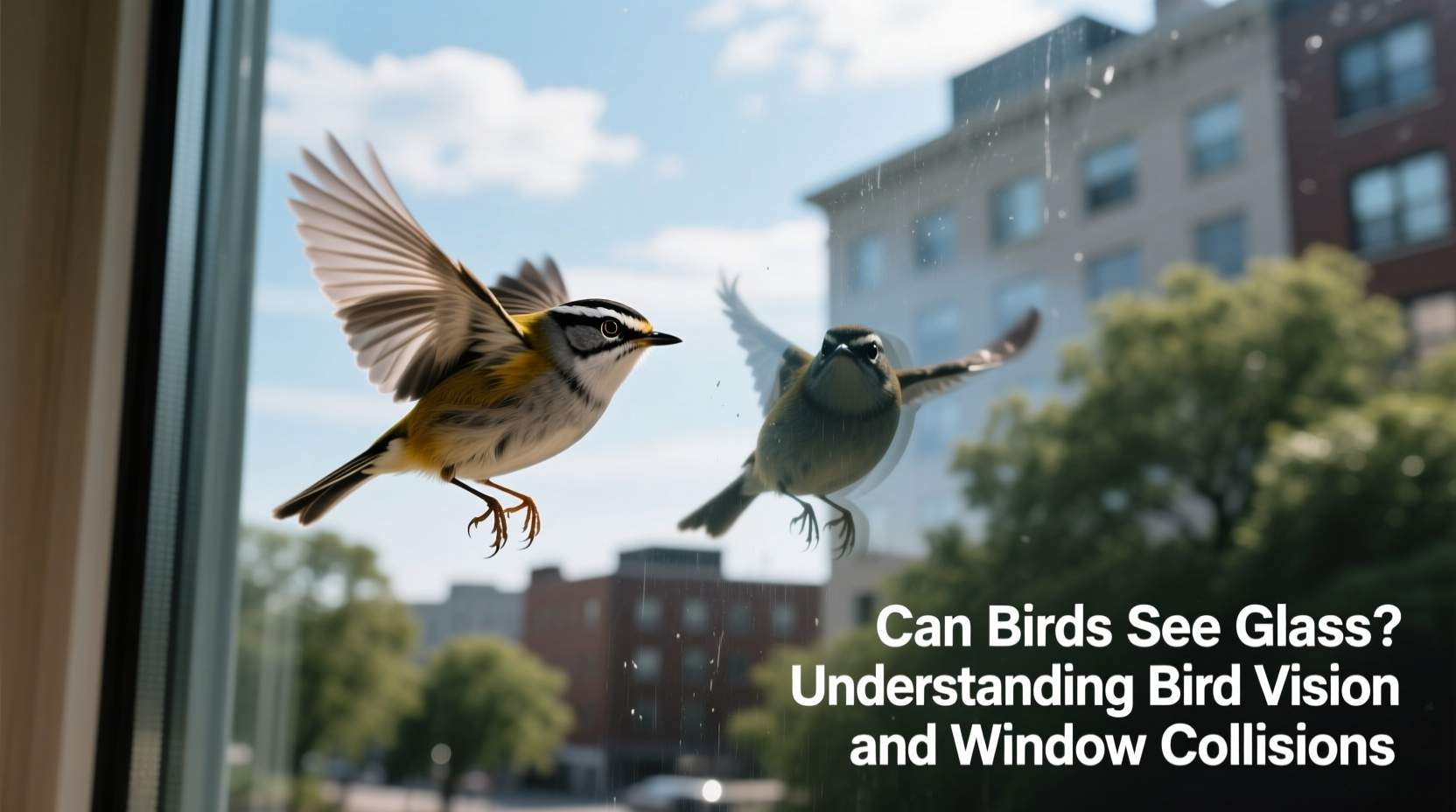

Birds cannot reliably see glass, which is why window collisions are a leading cause of bird mortality worldwide. The question can birds see glass has a clear answer: no, not in the way humans do. Transparent or reflective glass appears invisible to birds because they lack the visual cues we use to detect solid barriers. Instead of perceiving windows as obstacles, birds often interpret reflections of sky or vegetation as open flight paths, leading to fatal impacts. This misunderstanding between avian perception and human architecture underscores a growing conservation challenge—one that affects over a billion birds annually in North America alone.

The Science Behind Bird Vision and Glass Perception

To fully understand can birds see glass, it’s essential to examine how birds perceive their environment. Unlike humans, birds have eyes positioned on the sides of their heads, giving them a wide field of vision—sometimes nearly 360 degrees—ideal for detecting predators. However, this lateral eye placement reduces binocular vision and depth perception, making it harder for birds to judge distances accurately, especially when approaching flat, transparent surfaces.

Birds also process light differently. Many species can see ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths, which are invisible to humans. While this ability helps them locate food, choose mates, and navigate during migration, it does not help them detect glass. Most standard window glass absorbs UV light rather than reflecting it, so birds don’t see a visual signal that would warn them of a barrier. In essence, the very adaptations that make birds excellent fliers also leave them vulnerable to man-made structures.

Why Do Birds Fly Into Windows?

The phenomenon of birds colliding with glass is not due to poor eyesight or confusion—it’s a consequence of ecological mismatch. There are two primary reasons birds fail to recognize glass:

- Reflections of Sky and Trees: During daylight hours, windows often reflect surrounding landscapes. A bird sees what appears to be a continuation of the sky or nearby trees and attempts to fly through it, unaware of the solid surface.

- Transparency and Double Vision: When light conditions allow, birds may see through a window to indoor plants or outdoor scenery on the other side. From their perspective, there seems to be a clear flight path, especially in homes with open floor plans or glass passageways.

These factors are particularly dangerous during migration seasons—spring and fall—when millions of birds travel long distances and are already fatigued. Urban areas with large glass facades, such as office buildings and shopping centers, become deadly traps.

How Common Are Bird-Window Collisions?

Research estimates that between 365 million and one billion birds die each year in the United States due to window strikes. Canada reports an additional 42 million deaths annually. These numbers make building collisions the second-largest human-caused threat to birds after habitat loss and ahead of domestic cats.

Certain species are more vulnerable than others. Songbirds like warblers, thrushes, and sparrows are frequent victims due to their migratory behavior and tendency to fly at high speeds through wooded or suburban areas. However, even larger birds such as woodpeckers and raptors can suffer fatal injuries from collisions.

| Bird Species | Risk Level | Primary Cause of Collision |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow-rumped Warbler | High | Reflection of trees during migration |

| American Robin | Moderate | Seeing indoor plants through glass |

| Downy Woodpecker | High | Aggressive territorial behavior toward reflection |

| Dark-eyed Junco | Moderate | Low-altitude flight near residential windows |

| Cooper’s Hawk | Low to Moderate | Pursuing prey near buildings |

Debunking Common Myths About Birds and Glass

Several misconceptions persist about why birds hit windows and whether they can learn to avoid them. Let’s clarify some of these:

- Myth: Birds will eventually learn to avoid windows.

Reality: While individual birds might avoid a specific window after a non-fatal collision, most do not associate the impact with danger. Moreover, new generations of birds continue to encounter the same risks. - Myth: Only small birds are affected.

Reality: All sizes of birds can collide with glass. Larger birds may survive initial impacts but suffer internal injuries that lead to death later. - Myth: Putting up a single hawk silhouette sticker prevents collisions.

Reality: Studies show that isolated decals do little to deter birds. Effective solutions require coverage of at least 80% of the glass surface with patterns spaced no more than 2 inches apart horizontally or 4 inches vertically.

Proven Ways to Make Windows Bird-Safe

If you’re wondering can birds see glass and want to reduce the risk, here are practical, science-based strategies:

1. Apply External Window Films

UV-reflective or matte finish films are nearly invisible to humans but highly visible to birds. These coatings break up reflections and add texture that birds can detect. Look for products certified by the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) or tested by independent labs.

2. Install Screens or Netting

Exterior screens or bird-safe netting create a physical barrier that stops birds before they hit the glass. Even if a bird flies into the screen, the soft material absorbs impact and prevents injury.

3. Use Decals Strategically

If using stickers or decals, ensure they are placed on the outside of the glass and spaced closely. Patterns resembling branches, dots, or lines work best. Avoid placing them only on the inside, where they are less effective.

4. Move Indoor Plants Away from Windows

Plants near windows create the illusion of safe cover. By relocating them, you eliminate one of the main attractions that lure birds toward transparent panes.

5. Turn Off Lights at Night

Nocturnal migrants navigate using stars and moonlight. Brightly lit buildings disrupt their orientation and draw them into urban areas, increasing collision risks. Participating in programs like “Lights Out” during migration seasons can save thousands of birds.

Architectural Design and Policy Changes

Beyond individual actions, cities and architects are adopting bird-friendly design standards. Toronto, San Francisco, and New York City have implemented regulations requiring new buildings to use fritted glass, angled facades, or external shading devices that minimize reflections.

Fritted glass—glass with baked-in ceramic dots or lines—is particularly effective because it creates a visual pattern birds recognize as solid. Similarly, using less reflective glazing materials and avoiding glass corners in building designs significantly reduces collision risks.

What to Do If You Find a Bird That Hit a Window

If you discover a stunned or injured bird after a window strike, follow these steps:

- Wear gloves and gently place the bird in a ventilated box or paper bag.

- Keep it in a quiet, warm, dark place away from pets and children.

- Do not offer food or water unless trained to do so.

- Wait 1–2 hours to see if the bird recovers and flies away.

- If it remains incapacitated, contact a local wildlife rehabilitator.

Never assume a motionless bird is dead. Many recover after brief periods of shock.

Regional Differences and Seasonal Patterns

The frequency of bird-glass collisions varies by region and season. In temperate zones, peak collision times occur during spring (April–May) and fall (September–October) migrations. Tropical regions may see fewer seasonal spikes but still face risks from urban development.

Geographic location also influences risk. Suburban neighborhoods with abundant backyard feeders and dense tree cover adjacent to homes with large windows report higher incidents. Conversely, rural areas with minimal glass structures pose lower threats.

Climate plays a role too. On foggy or rainy days, glass becomes more reflective, increasing the chance of misperception. Early morning and late afternoon sunlight create strong glare, further obscuring window visibility.

How Researchers Study Bird-Glass Interactions

Scientists use several methods to study how birds interact with glass:

- Collision Monitoring Programs: Volunteers conduct daily surveys beneath buildings to document fatalities and near-misses.

- Flight Tunnel Experiments: Controlled tunnels allow researchers to observe how birds react to different types of treated versus untreated glass.

- Camera Surveillance: High-speed cameras capture real-time interactions, helping identify behavioral patterns.

- UV Reflectance Testing: Special instruments measure how much UV light various glass treatments reflect—key to understanding bird visibility.

These studies inform product development and policy recommendations, driving innovation in bird-safe materials.

FAQs About Birds and Glass Visibility

Can birds see glass at night?

No, birds cannot see glass at night either. In fact, artificial lighting increases the danger by attracting nocturnal migrants who may collide with illuminated buildings.

Do all types of glass pose the same risk?

No. Tempered, tinted, or fritted glass is less reflective and therefore safer. Clear, double-paned, and low-emissivity (Low-E) glass tends to be more hazardous due to increased reflectivity.

Are baby birds more likely to hit windows?

Yes. Juvenile birds, especially during fledging season (late spring to early summer), are inexperienced flyers and more prone to disorientation near human structures.

Does closing curtains prevent collisions?

Only partially. Interior curtains or blinds reduce transparency but do not eliminate reflections on the outside. For maximum effectiveness, combine interior coverings with exterior treatments.

Is there a law protecting birds from window collisions?

There is no federal law in the U.S. mandating bird-safe architecture, though some cities have local ordinances. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act offers limited protection, but enforcement regarding building design remains inconsistent.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4