Yes, birds can regurgitate contents from their stomachs, a process often mistaken for vomiting or throwing up, but it is physiologically and behaviorally distinct from mammalian vomiting. While the phrase can birds throw up might suggest a simple yes-or-no answer, the reality involves nuanced biological mechanisms, species-specific behaviors, and important distinctions between regurgitation and true emesis. Unlike humans and many mammals that forcefully expel stomach contents through coordinated muscular contractions involving the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, most birds lack a diaphragm and instead rely on esophageal and proventricular control to bring food back up—typically for feeding young, courtship, or eliminating indigestible material.

The Biological Basis of Avian Regurgitation

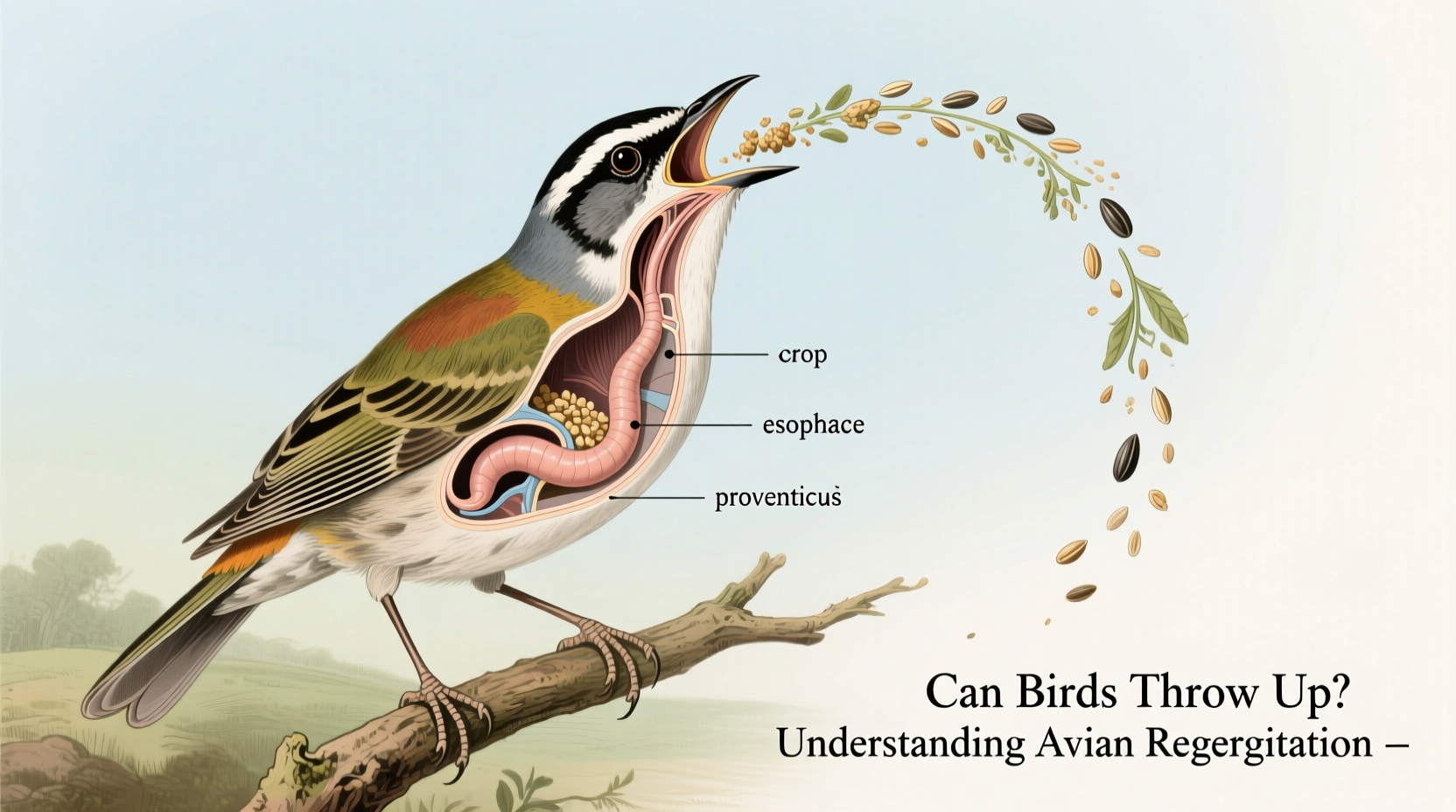

Birds possess a unique digestive system adapted to their high-energy lifestyles, flight demands, and dietary needs. The avian digestive tract includes the beak, esophagus, crop, proventriculus (glandular stomach), gizzard (muscular stomach), small intestine, ceca, large intestine, and cloaca. It is within this system—particularly at the level of the crop and proventriculus—that regurgitation occurs.

Regurgitation in birds is a controlled, voluntary process primarily used for parental care. For example, pigeons and doves produce “crop milk”—a nutritious secretion from the crop lining—to feed their squabs. Both male and female adults regurgitate this substance directly into the mouths of their offspring. Similarly, raptors such as hawks and owls tear prey into manageable pieces, partially digest them, and then regurgitate softened meals for their nestlings.

In contrast, true vomiting—or emesis—is a reflexive, involuntary response to toxins, illness, or gastrointestinal distress. Mammals achieve this through activation of the vomiting center in the brainstem, triggering reverse peristalsis and abdominal contraction. However, scientific evidence suggests that most birds do not have the same neural pathways or muscular coordination required for true vomiting. This raises an essential distinction: when people ask can birds throw up, they are usually observing regurgitation, not pathological vomiting.

Species That Exhibit Regurgitation Behavior

Not all birds regurgitate, and those that do use it for different purposes. Below is a breakdown of common bird groups known for regurgitative behaviors:

| Bird Group | Purpose of Regurgitation | Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeons & Doves | Feeding young with crop milk | Daily during nesting | Crop milk is rich in protein and fat; both parents participate |

| Raptors (Hawks, Owls, Eagles) | Feeding nestlings | Multiple times daily | Partially digested prey; bones and fur later expelled as pellets |

| Parrots & Cockatoos | Courtship feeding, chick rearing | Seasonal or social | May regurgitate to bonded humans—misinterpreted as affection |

| Kingfishers | Chick provisioning | During breeding season | Whole fish may be brought up and repositioned for easier swallowing |

| Pelicans & Gulls | Defensive mechanism | Rare, under stress | Gulls may eject stomach contents to reduce weight for flight or deter predators |

Do Birds Actually Vomit? The Exceptional Cases

While most birds cannot vomit in the mammalian sense, there are rare exceptions. Some studies suggest that certain seabirds, particularly tubenoses like albatrosses and petrels, can expel stomach oil as a defense mechanism. This oily substance, derived from their diet of squid and fish, is stored in the proventriculus and can be forcefully ejected up to several feet to repel predators or lighten body mass during escape.

This behavior, sometimes referred to as “spitting,” is closer to true vomiting than typical avian regurgitation because it involves expulsion of undigested, often noxious material under duress. However, even in these cases, the physiological mechanism differs from mammalian vomiting due to the absence of a diaphragm and different neuromuscular control.

Another exception occurs in waterfowl such as ducks and geese. There have been anecdotal reports and limited observations of ducks appearing to vomit after ingesting toxic algae or spoiled food. Yet, veterinary research indicates these instances may actually involve severe regurgitation triggered by irritation rather than a coordinated emetic reflex.

Why Can’t Most Birds Vomit?

The inability of most birds to vomit stems from evolutionary adaptations tied to flight. A lightweight, efficient body plan necessitates anatomical simplifications. Key factors include:

- Lack of a diaphragm: Birds rely on air sacs and rigid lungs for respiration. Without a diaphragm, they lack the primary muscle involved in creating the pressure differential needed for vomiting.

- Unidirectional airflow system: Their respiratory system is highly specialized and sensitive. Forceful abdominal contractions could disrupt airflow and compromise oxygen delivery—potentially fatal during flight.

- Esophageal structure: The bird esophagus is more flexible and less muscular than in mammals, making reverse peristalsis difficult without voluntary control.

- Evolutionary trade-offs: Since birds process food quickly and often consume diets low in toxins (especially insectivores and granivores), there was less evolutionary pressure to retain a vomiting reflex.

Instead of vomiting, birds have evolved alternative detoxification strategies, such as rapid digestion, selective feeding, and the production of uric acid instead of urea (which conserves water and reduces toxicity load).

Common Misconceptions About Birds Throwing Up

One of the most widespread misconceptions arises from pet bird owners who observe parrots or cockatiels bringing up food and assume it's vomiting due to illness. In reality, this is often regurgitation—a normal, healthy behavior associated with bonding or mating instincts. Owners unfamiliar with avian biology may unnecessarily panic or seek emergency vet care when none is required.

Conversely, some believe that because birds don’t vomit, they are immune to poisoning. This is dangerously false. Birds are highly sensitive to toxins—including avocado, chocolate, Teflon fumes, and zinc—and while they may not vomit, they can suffer acute toxicity leading to death within hours.

Another myth is that if a bird eats something harmful, inducing vomiting is a viable treatment. However, since birds cannot vomit naturally, attempting to induce it can cause aspiration pneumonia or physical injury. Always consult an avian veterinarian immediately in cases of suspected poisoning.

How to Tell If Your Bird Is Regurgitating or Ill

Distinguishing between normal regurgitation and signs of illness is crucial for bird caretakers. Here are key indicators:

Normal Regurgitation Signs:

- Occurs in context of feeding chicks or courting

- Bird bobs head rhythmically, often accompanied by cooing or wing quivering

- Expelled material is semi-solid, odorless, and resembles softened seed or pellet mash

- Bird appears alert and active afterward

Potential Illness Indicators:

- Projectile expulsion without head bobbing

- Foul-smelling, discolored, or bloody discharge

- Lethargy, fluffed feathers, loss of appetite

- Repeated attempts with little output (possibly indicating crop impaction)

- Difficulty breathing or wheezing post-event

If you suspect illness, isolate the bird, maintain warmth, and contact an avian veterinarian promptly. Do not attempt home remedies unless directed.

Observing Regurgitation in Wild Birds: Tips for Birdwatchers

For birdwatchers and researchers, recognizing regurgitation in the wild can provide insights into breeding behavior, diet, and social dynamics. Here’s how to identify and interpret it:

- Look for parent-offspring interactions: Watch adult birds approaching nests with bulging throats—this may indicate food storage in the crop prior to regurgitation.

- Listen for vocal cues: Nestlings often call persistently before being fed; adults may make soft clucking sounds during regurgitation.

- Note timing: Feeding peaks occur early morning and late afternoon, especially in songbirds and raptors.

- Avoid disturbance: Never approach active nests. Use binoculars or spotting scopes to observe from a safe distance.

- Document ethograms: Researchers can record frequency, duration, and participants in regurgitative events to study parental investment or pair bonding.

Implications for Avian Health and Conservation

Understanding whether birds can throw up has practical implications beyond curiosity. In conservation efforts, knowing that most birds cannot expel ingested pollutants means that plastic debris, lead shot, or chemical contaminants pose even greater risks. Once consumed, these materials remain in the digestive tract, potentially causing blockages, poisoning, or starvation.

Rehabilitation centers must also adapt protocols. For instance, when treating birds that have ingested toxins, veterinarians cannot rely on emetics. Instead, they use activated charcoal, fluid therapy, and supportive care. In cases of crop impaction, surgical intervention or manual evacuation may be necessary.

Additionally, urban environments increase exposure to human foods and waste. Bread-feeding, though popular, leads to nutritional deficiencies and mold ingestion, which birds cannot purge. Public education campaigns should emphasize that “feeding wildlife” often does more harm than good—especially when the animals lack the ability to rid themselves of poor-quality or toxic inputs.

FAQs: Common Questions About Birds and Vomiting

Can parrots throw up?

No, parrots cannot vomit like mammals. What appears to be vomiting is usually regurgitation—a normal behavior used for feeding mates or young. True vomiting is extremely rare and would indicate severe illness.

Why did my bird spit up its food?

If your bird brought up food gently with head-bobbing motions, it was likely regurgitating out of affection or instinct. If the ejection was forceful, smelly, or accompanied by distress, consult a vet immediately.

Can birds get food poisoning?

Yes, birds are highly susceptible to food poisoning from moldy seeds, spoiled fruit, or toxic substances like pesticides. Because they cannot vomit, symptoms progress rapidly and require urgent veterinary attention.

Do baby birds throw up?

No, nestlings do not vomit. Parents remove fecal sacs and may stimulate defecation, but regurgitation is performed only by adults. If a chick appears to be expelling food, it may be a sign of crop dysfunction or disease.

Is it bad if a bird regurgitates to me?

It’s not harmful, but it reflects that your bird sees you as a mate or close companion. While flattering, excessive regurgitation can lead to malnutrition. Encourage mental stimulation and set boundaries to discourage obsessive behaviors.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4