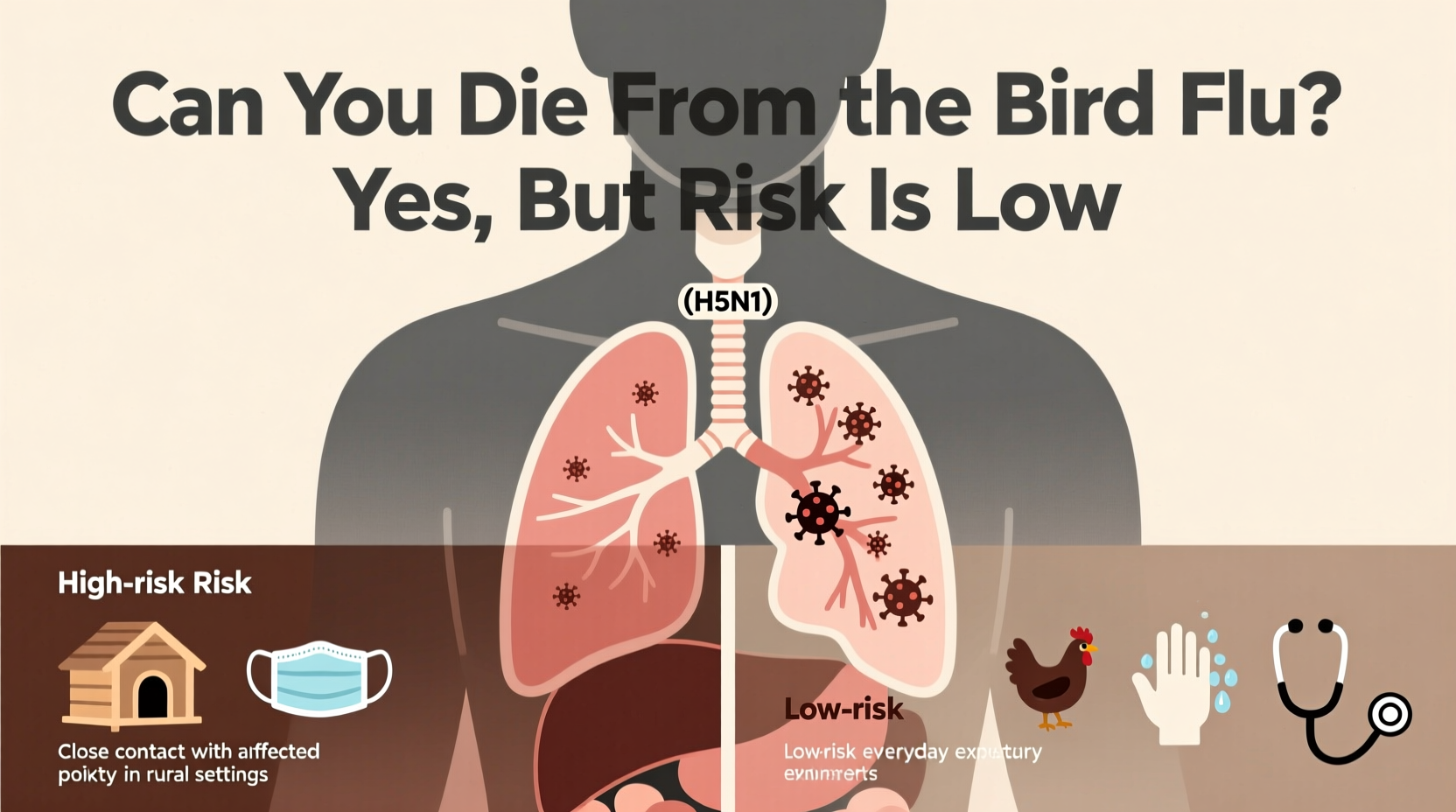

Yes, you can die from the bird flu, although human cases remain rare. The avian influenza virus, particularly subtypes like H5N1 and H7N9, has demonstrated the ability to cause severe respiratory illness and even fatalities in people who have had close contact with infected birds. While the risk to the general public remains low, understanding the transmission, symptoms, and prevention strategies is essential for those working with poultry or living in areas experiencing outbreaks. Can you get bird flu from touching a wild bird? Yes—this is one of the primary ways zoonotic transmission occurs.

Understanding Bird Flu: What It Is and How It Spreads

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. These viruses are naturally found in wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and swans, which often carry the pathogen without showing symptoms. However, when transmitted to domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys, avian flu can spread rapidly and cause high mortality rates among flocks.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds’ saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Contaminated surfaces, equipment, water sources, and even airborne particles in enclosed spaces can also serve as transmission routes. Although most strains do not easily infect humans, certain subtypes—including H5N1, H7N9, and more recently H5N6—have crossed the species barrier and caused serious illness in people.

Human infections typically occur after prolonged, unprotected exposure to sick or dead birds, especially during activities like slaughtering, defeathering, or handling raw poultry products. There is currently limited evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission, which helps prevent widespread pandemics—but sporadic cases continue to raise global health concerns.

Historical Outbreaks and Global Impact

The first known human case of H5N1 was reported in Hong Kong in 1997, sparking international alarm. Since then, hundreds of human infections have been documented across Asia, Africa, Europe, and parts of the Middle East. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 2003 and 2023, there were over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 worldwide, resulting in a fatality rate exceeding 50%.

In 2024, new variants of avian influenza emerged, including highly pathogenic H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which affected both commercial farms and backyard flocks across North America and Europe. This strain led to mass culling operations and travel advisories for bird enthusiasts visiting wetlands or wildlife reserves. While most human exposures remained occupational, isolated fatalities were reported in countries like Cambodia and Vietnam.

Another notable outbreak occurred with the H7N9 strain in China starting in 2013. Unlike H5N1, this variant caused mild symptoms in birds but triggered severe pneumonia in humans. Over 1,500 cases were recorded before aggressive control measures—including live poultry market closures—helped reduce transmission.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Humans

Initial signs of avian influenza in humans resemble those of seasonal flu: fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and fatigue. However, the disease can progress rapidly to more severe complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and septic shock.

Additional symptoms may include:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Chest pain or tightness

- Diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain

- Conjunctivitis (pink eye)

Incubation periods vary by strain but generally range from 2 to 8 days. Early diagnosis and antiviral treatment improve survival chances significantly. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are commonly prescribed within 48 hours of symptom onset.

Who Is at Highest Risk?

While anyone exposed to infected birds could potentially contract bird flu, certain groups face higher risks:

- Poultry farmers and farm workers

- Veterinarians and animal health inspectors

- Wildlife biologists and bird handlers

- People involved in live bird markets or home slaughter practices

- Travelers visiting regions with active outbreaks

Individuals with weakened immune systems, chronic lung diseases, or underlying health conditions may experience worse outcomes if infected. Children and older adults also appear more vulnerable to complications.

Can You Get Bird Flu From Eating Poultry or Eggs?

No, you cannot get bird flu from eating properly cooked poultry or eggs. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). As long as meat reaches an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C) and eggs are fully cooked until yolks and whites are firm, they pose no infection risk.

However, cross-contamination during food preparation remains a concern. Always wash hands, utensils, and cutting boards after handling raw poultry. Avoid consuming undercooked duck blood or traditional dishes made with uncooked eggs in outbreak zones.

Prevention and Safety Measures

Preventing bird flu involves minimizing exposure and practicing strict biosecurity protocols. Here are key recommendations:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds: Do not touch or handle wild birds, especially in areas reporting outbreaks.

- Use protective gear: When working with poultry, wear gloves, masks, goggles, and disposable clothing.

- Practice good hygiene: Wash hands frequently with soap and water, especially after being near birds or farms.

- Report unusual bird deaths: Contact local wildlife authorities if you find multiple dead birds in one location.

- Stay informed: Monitor updates from public health agencies like the CDC and WHO.

For travelers planning visits to rural areas in affected countries, consult national health advisories before departure. Some governments restrict entry for individuals coming from high-risk zones or require health screenings upon arrival.

Vaccination and Public Health Response

There is no widely available commercial vaccine for humans against bird flu, though candidate vaccines exist for stockpiling purposes. Seasonal flu shots do not protect against avian strains but are still recommended to reduce co-infection risks.

Public health responses focus on surveillance, rapid detection, and containment. When an outbreak occurs in poultry, authorities often implement:

- Mass culling of infected flocks

- Movement restrictions on live birds

- Enhanced screening at borders and airports

- Public education campaigns

In some countries, pre-pandemic vaccines are reserved for frontline workers and emergency responders. Research continues into universal influenza vaccines that could offer broader protection against multiple strains.

Differences Between Bird Flu and Seasonal Influenza

| Bird Flu (Avian Influenza) | Seasonal Human Flu |

|---|---|

| Caused by avian-specific influenza strains (e.g., H5N1, H7N9) | Caused by human-adapted strains (e.g., H1N1, H3N2) |

| Primarily spreads from birds to humans | Spreads easily person-to-person |

| Rare in humans; high fatality rate (~50–60%) | Common; low fatality rate (<0.1%) |

| No routine human vaccine available | Annual vaccines widely distributed |

| Most cases linked to direct bird contact | Spread via droplets in crowded settings |

Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Bird flu is spreading rapidly among people.

Reality: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred. Most cases are isolated and linked to animal exposure. - Misconception: All bird species are equally dangerous.

Reality: Waterfowl are natural carriers but rarely show illness. Chickens and turkeys suffer high death rates and pose greater biosecurity risks. - Misconception: Wearing a mask outdoors protects against bird flu.

Reality: Standard cloth masks offer little protection unless combined with other precautions like avoiding bird habitats.

What Should You Do If You Suspect Exposure?

If you’ve had close contact with infected birds and develop flu-like symptoms within 10 days, seek medical attention immediately. Inform your healthcare provider about your exposure history so they can test for avian influenza using nasopharyngeal swabs.

Quarantine yourself from others until results are confirmed. Follow isolation guidelines similar to those used during pandemic flu outbreaks. Antiviral medications may be administered prophylactically to household members or coworkers if deemed necessary.

Global Monitoring and Future Outlook

Organizations like the WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and CDC maintain global surveillance networks to track avian influenza in animals and humans. Real-time data sharing enables faster response times and helps identify emerging threats.

Climate change, intensified farming, and increased human-wildlife interaction may contribute to more frequent spillover events in the future. Scientists warn that continued viral evolution increases the risk of a strain gaining efficient human transmissibility—a scenario that could trigger a pandemic.

Ongoing research focuses on improving diagnostics, developing broad-spectrum antivirals, and enhancing early warning systems. Community engagement, especially in rural farming regions, plays a crucial role in preventing large-scale outbreaks.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you die from the bird flu?

Yes, bird flu can be fatal, particularly with strains like H5N1, which have mortality rates over 50% in confirmed human cases. - Is it safe to go birdwatching during an outbreak?

Yes, if you maintain distance from birds, avoid touching them, and follow local advisories. Use binoculars instead of approaching nests or roosts. - Are pets at risk of getting bird flu?

Cats can become infected by eating infected birds, though cases are rare. Keep cats indoors during outbreaks and report any sudden pet bird deaths to authorities. - Has bird flu reached the United States?

Yes, H5N1 has been detected in wild birds and poultry across many U.S. states. Human cases remain extremely rare, with only one non-fatal instance reported in 2022. - How is bird flu different from regular flu?

Bird flu originates in birds, causes more severe illness in humans, and lacks easy person-to-person spread compared to seasonal flu.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4