Birds are not mammals; they are a distinct class of vertebrate animals known as Aves, characterized by feathers, beaks, laying hard-shelled eggs, and the ability to fly—though not all species can fly. This fundamental distinction separates birds from mammals, which are warm-blooded vertebrates that typically give birth to live young and nurse them with milk produced by mammary glands. Understanding whether your bird is a mammal touches on both biological classification and common misconceptions perpetuated in casual conversation. The question 'are birds mammals' is one of the most frequently searched con your bird queries, especially among students, educators, and new bird enthusiasts trying to clarify basic zoological categories.

Biological Classification: What Makes a Bird a Bird?

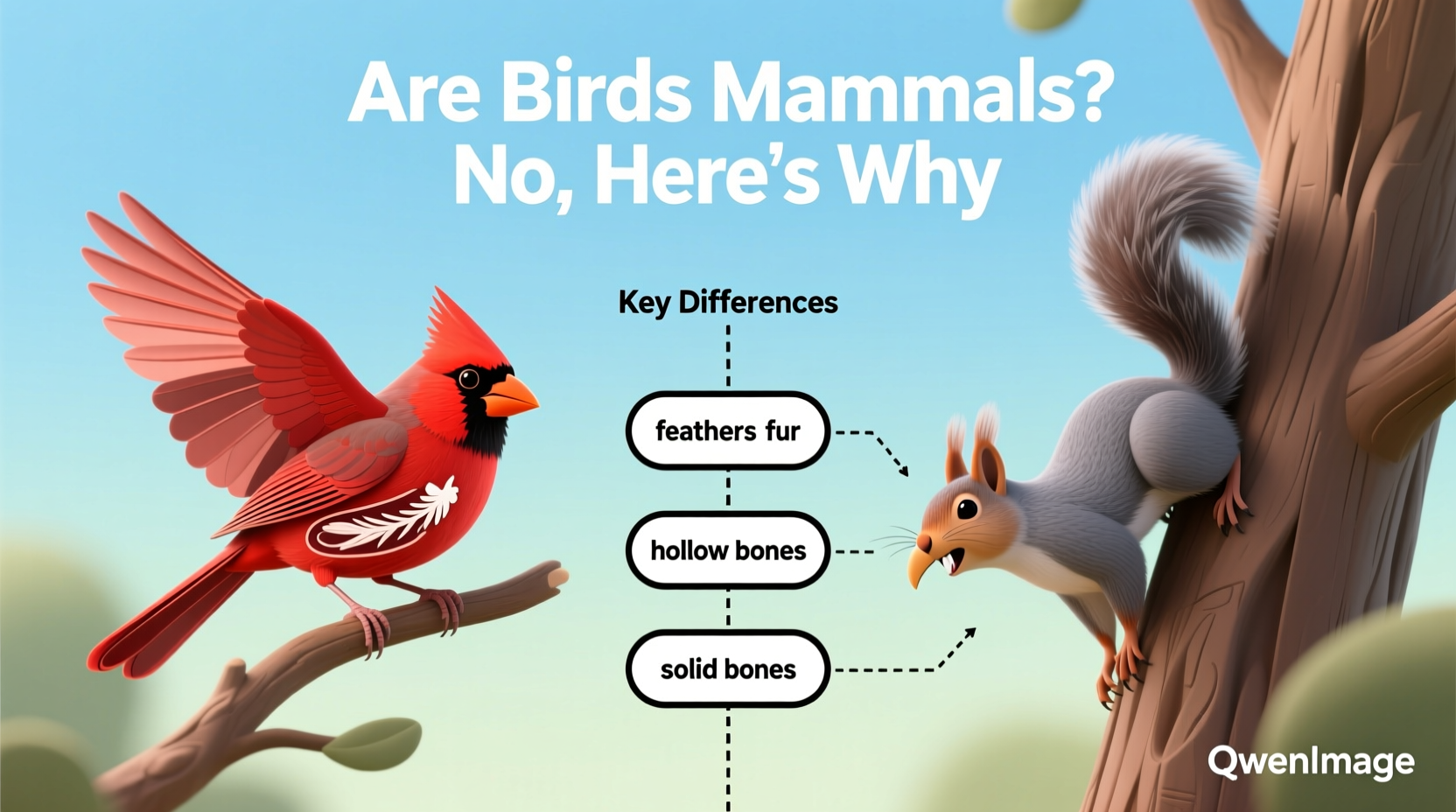

The scientific classification of birds places them in the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, and class Aves. Unlike mammals (class Mammalia), birds possess several unique anatomical and physiological traits. Feathers are perhaps the most defining feature—no other animal group has true feathers. These specialized structures evolved from reptilian scales and serve multiple functions including flight, insulation, and display.

Birds are also bipedal, meaning they walk on two legs, and most have wings adapted for flight. Their skeletal system is lightweight due to hollow bones, an adaptation crucial for aerial locomotion. Additionally, birds have a highly efficient respiratory system with air sacs that allow for continuous airflow through the lungs, enabling high metabolic rates needed for sustained flight.

Another key difference lies in reproduction. Birds lay amniotic eggs with calcified shells, usually incubated in nests. In contrast, nearly all mammals give birth to live young (except monotremes like the platypus) and nourish their offspring with milk. These biological distinctions firmly place birds outside the mammalian category.

Evolutionary Origins: Birds and Dinosaurs

Modern birds are considered the only living descendants of dinosaurs, specifically theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex. Fossil evidence, especially from China’s Liaoning Province, shows transitional species such as Archaeopteryx and Microraptor that exhibit both reptilian and avian features—including teeth, long bony tails, and feathered limbs.

This evolutionary link underscores why birds share certain traits with reptiles rather than mammals. For example, birds and reptiles both lay eggs and have similar skin structures without hair or sweat glands. Their closest living relatives are crocodilians, not mammals, despite both birds and mammals being warm-blooded (endothermic). This convergence in thermoregulation evolved independently and does not imply close relation.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Mammals

One widespread misconception is that because birds are warm-blooded and care for their young, they must be mammals. However, endothermy has evolved multiple times across different lineages. Bats, the only flying mammals, are often confused with birds due to their aerial lifestyle, but bats have fur, give live birth, and lactate—all hallmarks of mammalian biology.

Another confusion arises with flightless birds like penguins or ostriches. Despite their inability to fly, they still possess feathers, lay eggs, and have avian skeletal structures—confirming their status as birds. Similarly, baby birds hatching from eggs and being fed regurgitated food might resemble parental care seen in mammals, but the method of nourishment and developmental biology remain distinctly non-mammalian.

The phrase 'con your bird' often emerges in online forums where users seek clarification on pet ownership myths, such as believing pet birds need milk or can bond like mammalian pets. In reality, birds form strong social bonds but express affection differently—through vocalizations, preening, or following their owners—which should not be anthropomorphized.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds hold profound symbolic meanings in human cultures worldwide. In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird—a precursor to the Greek phoenix—symbolized rebirth and immortality. Native American traditions often regard eagles as messengers between humans and the divine, while owls represent wisdom in Greek mythology and ill omens in some African and Asian cultures.

In literature and art, birds frequently symbolize freedom, transcendence, and the soul’s journey. The dove, universally associated with peace, appears in Christian iconography as the Holy Spirit. Conversely, ravens and crows are linked to mystery and intelligence, celebrated in Norse mythology as Odin’s spies.

These cultural narratives sometimes blur scientific understanding. For instance, calling someone "bird-brained" implies stupidity, yet many birds—especially corvids and parrots—demonstrate advanced problem-solving skills, tool use, and even self-recognition in mirrors, rivaling primates in cognitive tests.

Practical Guide to Observing and Caring for Birds

Whether you're a backyard observer or a dedicated birder, understanding bird behavior enhances both appreciation and conservation efforts. Here are essential tips for engaging with birds responsibly:

- Use binoculars and field guides: Invest in quality optics and region-specific identification books or apps like Merlin Bird ID or eBird.

- Visit during peak activity times: Early morning and late afternoon are optimal for birdwatching when species are most active.

- Minimize disturbance: Keep noise low, avoid sudden movements, and never approach nests or feed wild birds inappropriate foods (e.g., bread).

- Create bird-friendly spaces: Plant native vegetation, provide clean water sources, and install nest boxes suited to local species.

If you keep pet birds, remember they require mental stimulation, proper diet (seed-only diets are inadequate), and regular veterinary checkups with an avian specialist. Unlike mammals, birds mask illness well, so subtle changes in posture, appetite, or droppings warrant immediate attention.

Regional Differences in Bird Species and Behavior

Bird diversity varies dramatically by geography. Tropical regions like the Amazon Basin host over 1,300 bird species, while Arctic tundras may see fewer than 50 breeding species annually. Migration patterns further complicate regional observations—many songbirds travel thousands of miles between breeding and wintering grounds.

In North America, spring migration peaks April–May, offering excellent viewing opportunities along flyways like the Mississippi River. In Europe, autumn migration brings seabirds and waders southward across the Mediterranean. Urban environments support adaptable species like pigeons, sparrows, and starlings, whereas forests, wetlands, and deserts harbor specialists dependent on specific habitats.

Climate change is altering these dynamics. Some species are shifting ranges northward or arriving earlier in spring, disrupting ecological synchrony (e.g., insects emerging before chicks hatch). Citizen science projects like Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count help track these changes over time.

How to Verify Information About Birds

With abundant misinformation online, it's vital to consult authoritative sources. Trusted organizations include the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, National Audubon Society, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Peer-reviewed journals such as The Auk and The Condor publish rigorous research on avian biology.

When questioning whether a trait applies to all birds—such as flight capability or nesting habits—always consider exceptions. Flightless birds include not just ostriches and emus but also kiwis and rails. Nesting behaviors range from elaborate weaver nests to simple ground scrapes used by plovers.

To confirm if a local species is protected or regulated, consult government wildlife agencies (e.g., U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, DEFRA in the UK). Laws governing possession, banding, or rehabilitation vary widely and often restrict keeping native birds as pets.

| Feature | Birds (Class Aves) | Mammals (Class Mammalia) |

|---|---|---|

| Skin Covering | Feathers | Fur or Hair |

| Reproduction | Lay hard-shelled eggs | Most give live birth |

| Young Nourishment | No milk; fed regurgitated food | Nursed with milk from mammary glands |

| Body Temperature | Warm-blooded (endothermic) | Warm-blooded (endothermic) |

| Skeletal Structure | Hollow bones, lightweight | Dense bones |

| Respiratory System | Lungs with air sacs, unidirectional airflow | Lungs with alveoli, bidirectional airflow |

| Heart Chambers | Four-chambered heart | Four-chambered heart |

| Examples | Eagle, sparrow, penguin, hummingbird | Dog, whale, bat, human |

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are birds cold-blooded? No, birds are warm-blooded (endothermic), maintaining a constant internal body temperature regardless of environment.

- Can birds think and feel emotions? Yes, studies show birds experience pain, fear, and pleasure. Advanced species demonstrate complex cognition, memory, and social learning.

- Why do people confuse birds with mammals? Because both are warm-blooded and care for their young, but reproductive and anatomical differences clearly separate them.

- Is a bat a bird? No, bats are mammals. They have fur, give live birth, and produce milk—despite being capable of flight.

- Do all birds fly? No, about 60 extant bird species are flightless, including ostriches, cassowaries, and several island-endemic rails.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4