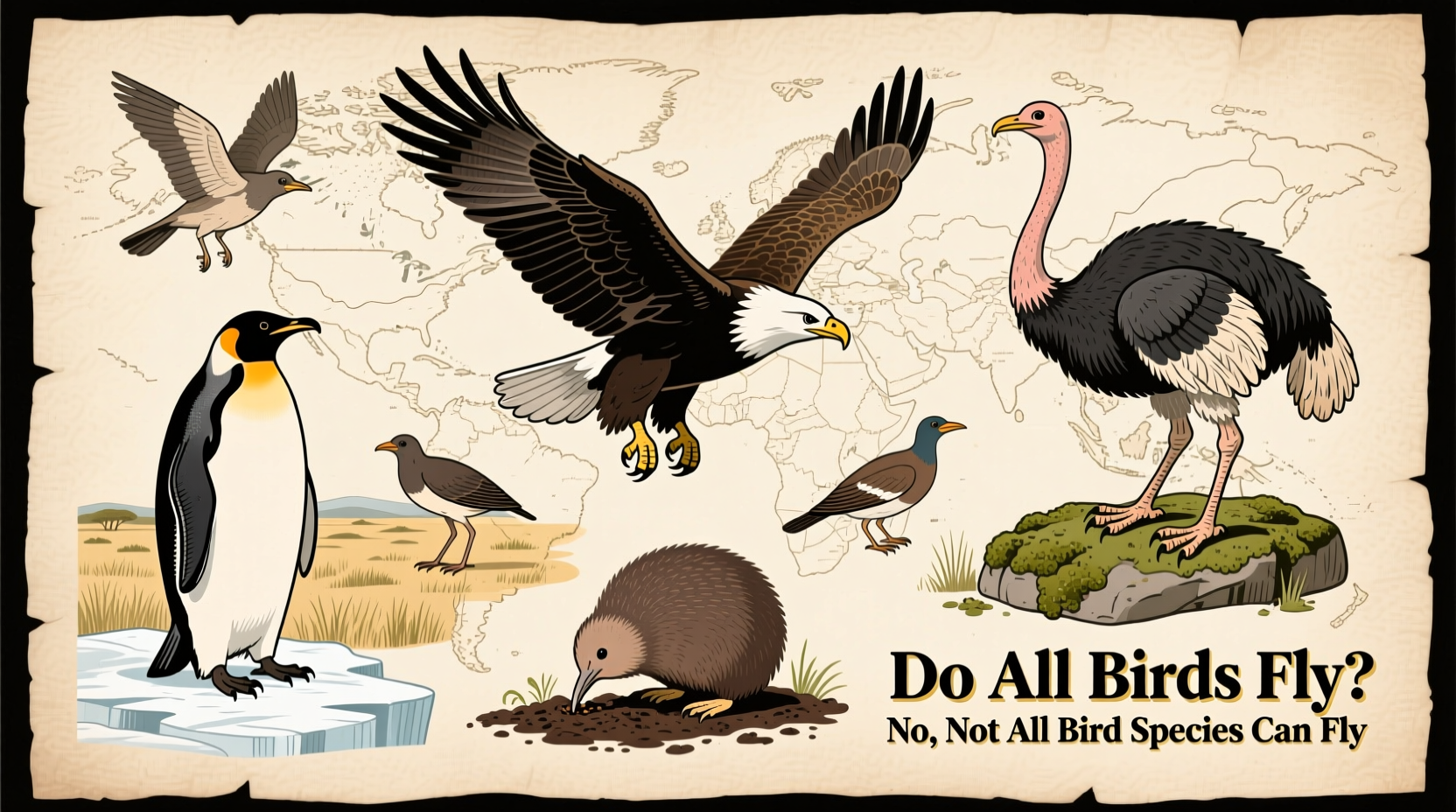

No, not all birds fly. While the majority of bird species are adapted for flight, a significant number have evolved to become flightless due to isolation, lack of predators, or specialized ecological niches. This variation in avian locomotion answers the common question: do all birds fly, and reveals a fascinating aspect of evolutionary biology. Flightlessness has independently emerged in multiple bird lineages across the globe, particularly on islands or in stable environments where flying was no longer necessary for survival. Understanding which birds can't flyâand whyâoffers insight into adaptation, conservation, and the diversity of life strategies among birds.

Understanding Flight in Birds: The Evolutionary Advantage

Flight is one of the defining characteristics of most birds. It allows them to escape predators, migrate long distances, access food sources, and find mates across vast territories. The anatomy of flying birds reflects this specialization: lightweight skeletons with hollow bones, powerful pectoral muscles, streamlined bodies, and asymmetrical flight feathers that generate lift and thrust.

Birds such as swallows, albatrosses, and hummingbirds showcase the extreme adaptations made possible by flight. For example, the Arctic tern migrates over 40,000 miles annually between breeding and wintering groundsâa feat entirely dependent on its ability to fly. These examples highlight how central flight is to the lifestyle of many avian species.

However, evolution does not always favor flight. When energy costs outweigh benefitsâsuch as in predator-free environments or where food is abundant and stationaryânatural selection may favor individuals who invest less energy in maintaining flight muscles and more in reproduction or size. Over generations, these pressures lead to flightlessness.

Flightless Birds: Examples and Characteristics

Approximately 60 extant bird species are flightless, belonging to diverse taxonomic groups. Some of the most well-known include:

- Ostrich (Africa)

- Emu (Australia) \li>Cassowary (New Guinea and northeastern Australia)

- Kiwi (New Zealand)

- Penguin (Southern Hemisphere, especially Antarctica)

- Takahe (New Zealand)

- Weka (New Zealand)

- Rhea (South America)

- Kakapo (New Zealand)

These birds share certain anatomical traits: reduced keel on the sternum (where flight muscles attach), smaller wing structures relative to body size, and heavier overall body mass. Penguins, though flightless in air, have evolved wings modified into flippers for efficient underwater 'flight' while swimming.

Why Can't Some Birds Fly? Evolutionary and Ecological Reasons

The loss of flight typically occurs under specific ecological conditions:

- Absence of terrestrial predators: On isolated islands like New Zealand or Madagascar, native birds evolved without mammalian predators. Without pressure to flee quickly, flight became expendable.

- Energy conservation: Maintaining flight muscles consumes significant metabolic resources. In stable environments, redirecting energy toward growth, reproduction, or fat storage offers survival advantages.

- Niche specialization: Some birds evolved to fill ground-based roles similar to mammalsâgrazing, digging, or running fastâmaking flight unnecessary.

For instance, the kiwi bird of New Zealand forages at night using an acute sense of smell, a trait rare among birds but useful for probing soil for insects. Its small wings are vestigial, hidden beneath hair-like feathers, showing how form follows function in evolution.

Geographic Distribution of Flightless Birds

Flightless birds are disproportionately found on islands, especially those in the Southern Hemisphere. New Zealand stands out as a hotspot, historically home to moas (now extinct), takahes, kiwis, and the kakapoâall flightless. Similarly, Madagascar once hosted elephant birds, and Hawaii had flightless geese before human arrival.

Continental regions also host flightless species. The ostrich of Africa is the largest living bird and can run up to 45 mphâits primary defense mechanism. Rheas in South America and cassowaries in New Guinea serve similar ecological roles as large, fast-running herbivores and omnivores.

This distribution pattern underscores the role of geographic isolation in enabling flightlessness to evolve safely, away from invasive predators.

Are Flightless Birds at Greater Risk?

Unfortunately, yes. Many flightless birds are endangered or extinct due to human activity. Their inability to fly makes them vulnerable to introduced predators such as rats, cats, dogs, and stoats. Additionally, habitat destruction and hunting have severely impacted populations.

Examples include:

- Moa: A group of giant flightless birds in New Zealand hunted to extinction by MÄori settlers within centuries of human arrival (~1300â1400 CE).

- Dodo: Native to Mauritius, this flightless pigeon was driven extinct by sailors and invasive species by the late 17th century.

- Kakapo: Critically endangered; only around 250 individuals remain, all managed under intensive conservation programs in predator-free sanctuaries.

Conservation efforts often involve relocating flightless birds to offshore islands cleared of predators or implementing strict biosecurity measures. Captive breeding and genetic monitoring play key roles in preserving these unique species.

Can Flightless Birds Ever Regain Flight?

In evolutionary terms, regaining complex traits like flight after losing them is extremely unlikely. Once the genetic and morphological pathways for flight degrade over millions of years, reversing that process would require immense selective pressure and timeâfar beyond typical ecological timescales.

While some birds may regain limited gliding or flapping abilities under experimental models, there is no documented case of a fully flightless lineage re-evolving powered flight. Instead, these species adapt through other meansâspeed, camouflage, or behavioral changesâto survive.

Observing Flightless Birds: Tips for Birdwatchers

If you're interested in seeing flightless birds in the wild or captivity, here are practical tips:

- Visit protected reserves: In New Zealand, sanctuaries like Zealandia (near Wellington) offer guided tours to observe kiwis and takahes in semi-wild enclosures.

- Respect viewing distances: Cassowaries and ostriches can be aggressive if threatened. Always follow local guidelines when observing in national parks.

- Check zoo accreditation: Reputable zoos participate in Species Survival Plans (SSPs). Facilities like San Diego Zoo and Bronx Zoo house rheas, emus, and penguins with educational programming.

- Support conservation tourism: Eco-tours focused on native wildlife often fund preservation initiatives directly.

When planning trips, research seasonal behaviorsâsome flightless birds breed during specific months or are nocturnal (like the kiwi), requiring special night-viewing permits.

Common Misconceptions About Flightless Birds

Several myths persist about non-flying birds:

- Myth: Flightless birds are 'primitive' or evolutionary failures.

Reality: They are highly evolved for their environments. Losing flight is an adaptive success in safe ecosystems. - Myth: All penguins live in Antarctica.

Reality: While emperor and Adélie penguins inhabit Antarctica, others like the Galápagos penguin live near the equator. - Myth: If a bird has wings, it must be able to fly.

Reality: Wings serve various functionsâbalance, display, thermoregulation, swimmingâeven when flight is absent.

| Bird Species | Native Region | Flight Capability | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich | Africa | Flightless | Least Concern |

| Kiwi | New Zealand | Flightless | Vulnerable to Endangered (by species) |

| Penguin (Emperor) | Antarctica | Flightless (in air) | Least Concern |

| Rhea | South America | Flightless | Near Threatened |

| Kakapo | New Zealand | Flightless | Critically Endangered |

How to Identify Potential Flightlessness in Birds

Birdwatchers can look for physical clues indicating flightlessness:

- Wing-to-body ratio: Short, stubby wings relative to body size suggest flightlessness.

- Sternum structure: Though hard to see in live birds, a reduced or flat keel indicates underdeveloped flight muscles.

- Leg development: Strong, elongated legs adapted for running (e.g., ostriches) often correlate with loss of flight.

- Habitat: Ground-dwelling birds in isolated areas are more likely to be flightless.

Using field guides with anatomical diagrams and consulting databases like the IUCN Red List or eBird can help confirm identification and conservation status.

Final Thoughts: Diversity Beyond Flight

The answer to âdo all birds flyâ is clearly noâbut this limitation opens a window into the broader story of adaptation and biodiversity. Flightlessness is not a defect but a testament to natureâs flexibility. From the deep dives of penguins to the moonlit foraging of kiwis, flightless birds occupy vital ecological roles and inspire awe in their own right.

As global change threatens fragile island ecosystems, protecting these unique species becomes ever more urgent. Whether through scientific study, responsible ecotourism, or public education, understanding flightless birds enriches our appreciation of avian life in all its forms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can any flightless birds glide or jump?

No known flightless bird can glide effectively. However, some, like young rails or steamer ducks, may use partial wing-assisted leaps to escape danger, though they cannot sustain flight.

Why did the dodo lose the ability to fly?

The dodo evolved on Mauritius with no natural predators and abundant food. Over time, individuals that allocated fewer resources to flight muscles had higher reproductive success, leading to complete flight loss.

Are there any flightless birds in North America?

Currently, there are no naturally occurring flightless bird species native to mainland North America. However, some domesticated breeds like certain chickens or turkeys have limited flight capability due to selective breeding.

Do baby birds of flightless species attempt to fly?

No. Chicks of flightless birds show no instinct to flap for flight. Instead, they follow parental cues for running, hiding, or swimming depending on the species.

Could climate change affect flightless bird survival?

Yes. Rising sea levels threaten low-lying island habitats, while changing temperatures may alter food availability. Additionally, shifting weather patterns could facilitate the spread of invasive species into previously protected areas.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4