All birds, without exception, have feathers. This defining characteristic is what sets avian species apart from all other animals on Earth. The presence of feathers is not only a biological hallmark of birds but also central to their survival, flight, and thermoregulation. When exploring the question do all birds have feathers, the answer is a definitive yesâfeathers are universal among birds, from the tiniest hummingbird to the towering ostrich. While feather appearance, density, and function can vary dramatically across species, every bird alive today possesses some form of feathers at some stage in its life cycle.

The Biological Necessity of Feathers in Birds

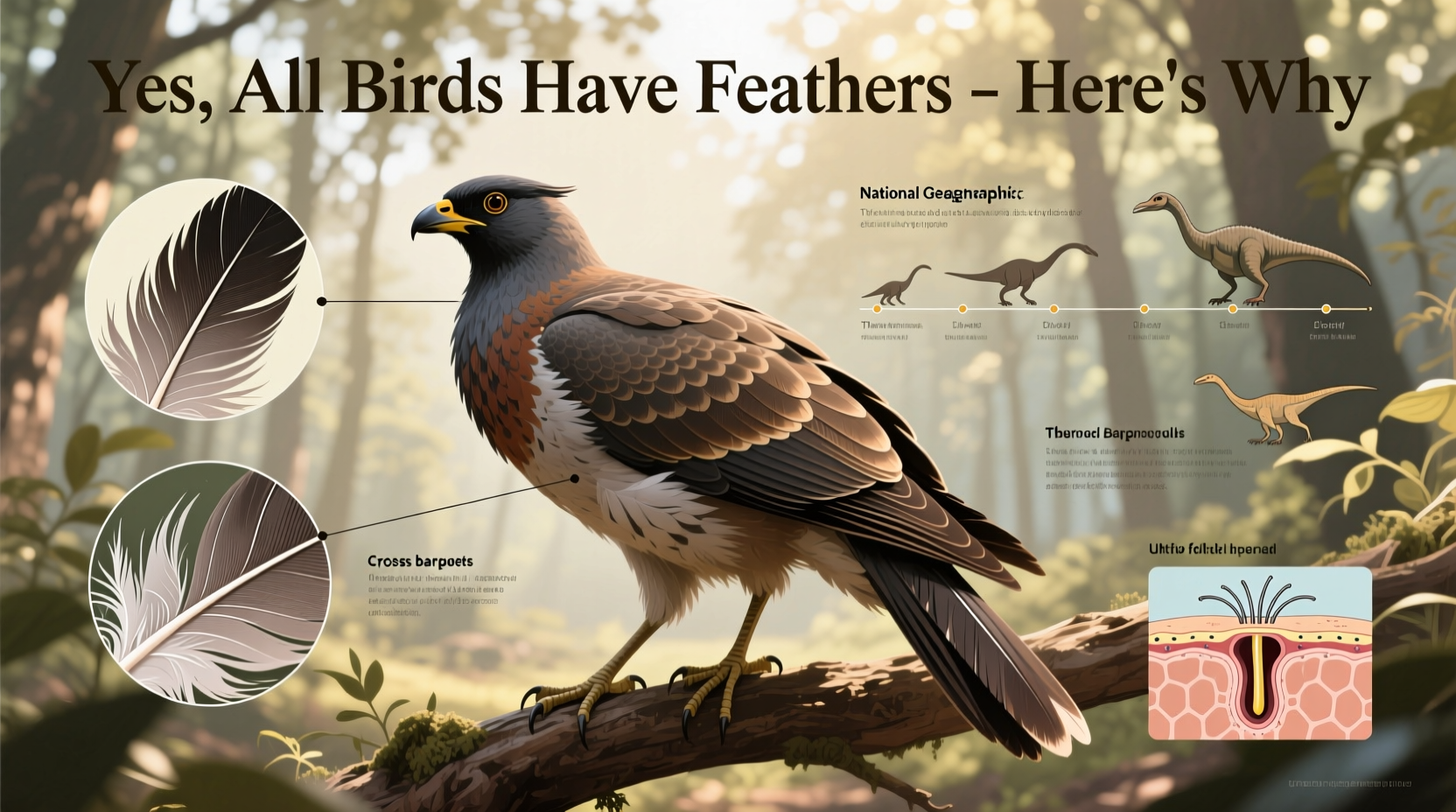

Feathers are complex structures made primarily of keratin, the same protein found in human hair and nails. They evolved from reptilian scales over millions of years and represent one of the most sophisticated adaptations in the animal kingdom. Unlike fur or hair, feathers serve multiple critical functions: enabling flight, providing insulation, aiding in camouflage, and playing roles in mating displays and communication.

There are several types of feathers, each serving a distinct purpose:

- Contour feathers: These give birds their streamlined shape and include flight feathers on wings and tails.

- Down feathers: Soft and fluffy, they trap air close to the body for warmth. \li>Flight feathers: Stiff and strong, located on wings (remiges) and tail (rectrices), essential for lift and steering.

- Semiplumes: Intermediate feathers that provide both insulation and shape.

- Bristles and filoplumes: Specialized feathers involved in sensory perception and display.

Even flightless birds like penguins and emus have feathersâthough adapted differently. Penguins have short, dense feathers that create a waterproof layer crucial for swimming in frigid waters. Emus possess double-shafted feathers that insulate against extreme temperatures in the Australian outback. These examples reinforce that while functionality may shift, the presence of feathers remains constant.

Evolutionary Origins of Feathers

Fossil evidence suggests that feathers predate modern birds by tens of millions of years. Discoveries of feathered dinosaurs such as Sinosauropteryx and Microraptor in China reveal that primitive feathers existed in non-avian theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period. These early feathers were likely used for insulation or display rather than flight, indicating that feathers evolved first for purposes other than aerial locomotion.

The transition from dinosaur to bird is best exemplified by Archaeopteryx, a creature dating back approximately 150 million years. It had fully formed flight feathers and skeletal features intermediate between reptiles and modern birds. This fossil provides compelling evidence that feathers were already well-developed before powered flight emerged.

Modern birds belong to the class Aves, which evolved from small, feathered dinosaurs after the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. All living birds share a common ancestor that possessed feathers, which explains why this trait is universally conserved across more than 10,000 known bird species today.

Feather Development Across Life Stages

While all birds have feathers, not all hatchlings are immediately covered in them. Altricial birdsâsuch as robins, hawks, and songbirdsâare born naked and blind, developing feathers over days or weeks. In contrast, precocial birdsâincluding ducks, chickens, and quailsâare born with a downy coat that allows them to regulate body temperature and move shortly after hatching.

Feather growth occurs through a process called molting, where old feathers are shed and replaced periodically. Most birds molt once or twice a year, though some species undergo partial or sequential molts depending on migration patterns, breeding cycles, and environmental conditions. Molting ensures that feathers remain functional and intact for flight, insulation, and protection.

Itâs important to note that even birds undergoing heavy molts retain some feathers at all times. There is no known stage in a bird's life when it becomes completely featherless under normal circumstances. Temporary loss due to stress, disease, or injury does not negate the fact that feathers are an intrinsic part of avian biology.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Feathers

Feathers have held deep symbolic meaning across human cultures throughout history. In many Indigenous traditions of North America, feathersâespecially eagle feathersâare sacred objects representing courage, wisdom, and spiritual connection. They are often awarded in ceremonies and worn with great respect.

In ancient Egypt, the goddess Maâat was depicted with an ostrich feather, symbolizing truth and justice. During judgment in the afterlife, a personâs heart was weighed against this feather; if balanced, the soul could proceed into the afterlife.

In European heraldry, feathers denoted nobility and rank. Plumes adorned helmets and coats of arms, signifying valor and lineage. Meanwhile, in Victorian-era fashion, exotic bird feathers became status symbols, leading to widespread plume hunting that decimated populations of egrets, birds of paradise, and other speciesâan ecological tragedy that eventually spurred early conservation movements.

Today, feathers continue to inspire art, literature, and spirituality. Their association with flight makes them metaphors for freedom, transcendence, and aspiration. Understanding that do all birds have feathers underscores how deeply intertwined these structures are with both natural science and human culture.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Feathers

Despite scientific consensus, several myths persist about birds and feathering. One common misconception is that flightless birds do not have feathers. As previously explained, this is false. Ostriches, cassowaries, kiwis, and penguins all have feathersâalbeit modified for ground running, swimming, or insulation.

Another myth is that baby birds are âborn without skinâ or ânaked like mice.â While altricial chicks lack mature contour feathers at birth, they still develop feather follicles early in embryonic development. Down feathers emerge within hours or days, confirming that feathering is genetically programmed from conception.

A third misunderstanding involves featherless-looking birds seen in urban areasâoften pigeons or grackles suffering from feather mites or nutritional deficiencies. These individuals are exceptions caused by illness, not representative of the species as a whole. Such cases should not be mistaken as evidence that some birds naturally lack feathers.

Observing Feathers in the Wild: Tips for Birdwatchers

For amateur and experienced birdwatchers alike, understanding feather structure enhances field observation. Here are practical tips for identifying birds based on their plumage:

- Use binoculars with high resolution: Look for fine details in wing bars, tail patterns, and crown feathers that help distinguish similar species.

- Observe seasonal changes: Many birds molt into brighter breeding plumage in spring. Knowing when these transitions occur improves identification accuracy.

- Note feather wear and condition: Worn or ragged flight feathers may indicate recent migration or poor health.

- Photograph feathers on the ground: Finding molted feathers can offer clues about local species presenceâeven when birds themselves are hidden.

When documenting sightings, consider using apps like eBird or Merlin Bird ID, which allow users to upload photos and receive automated suggestions based on feather coloration and pattern. Always follow ethical guidelines: avoid disturbing nesting birds or collecting feathers from protected species, especially eagles and other raptors, which are legally protected under laws like the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Regional Variations and Feather Adaptations

Birds in different climates exhibit remarkable feather adaptations. Arctic species like the snowy owl have densely packed down beneath outer feathers to survive subzero temperatures. Desert-dwelling birds such as roadrunners have sparser feather coverage to prevent overheating, relying instead on behavioral thermoregulation like sunbathing or shade-seeking.

In tropical rainforests, birds like toucans and parrots boast vibrant feathers used in mate attraction and social signaling. Iridescence in hummingbirds results from microscopic feather structures that refract light, creating dazzling visual effects without pigmentation.

Coastal seabirds like puffins and gannets have tightly interlocking feathers coated with oils from the uropygial gland, forming a waterproof barrier essential for diving and swimming. These regional differences highlight how feather function evolves in response to environmental pressures, yet never disappears entirely.

| Bird Type | Feather Characteristics | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hummingbird | Iridescent, rapid-molt cycle | Display, flight agility |

| Penguin | Short, stiff, overlapping | Waterproofing, insulation |

| Ostrich | Soft, fluffy, double-shafted | Thermoregulation, display |

| Barn Owl | Silent-flight remiges | Stealth hunting |

| Peacock | Elongated train with eye spots | Mate attraction |

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds have feathers, including newborns?

- Yes, all birds have feathers at some point in their lives. While some hatchlings are born without visible feathers, they quickly develop down and later grow adult plumage.

- Are there any birds without feathers?

- No. Even flightless and aquatic birds have feathers. Temporary feather loss due to disease or stress does not change the biological rule that all birds possess feathers.

- Can feathers indicate a birdâs health?

- Absolutely. Dull coloration, broken shafts, or patchy molting can signal malnutrition, parasites, or environmental toxins. Healthy feathers are smooth, aligned, and vibrant.

- Why do some birds look bald?

- Some vultures and storks have bare heads as an adaptation to scavengingâthey reduce bacterial buildup when feeding inside carcasses. However, their bodies are fully feathered.

- Is it legal to collect bird feathers?

- Laws vary by country. In the United States, collecting feathers from native migratory birds, especially raptors, is prohibited without a permit under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4