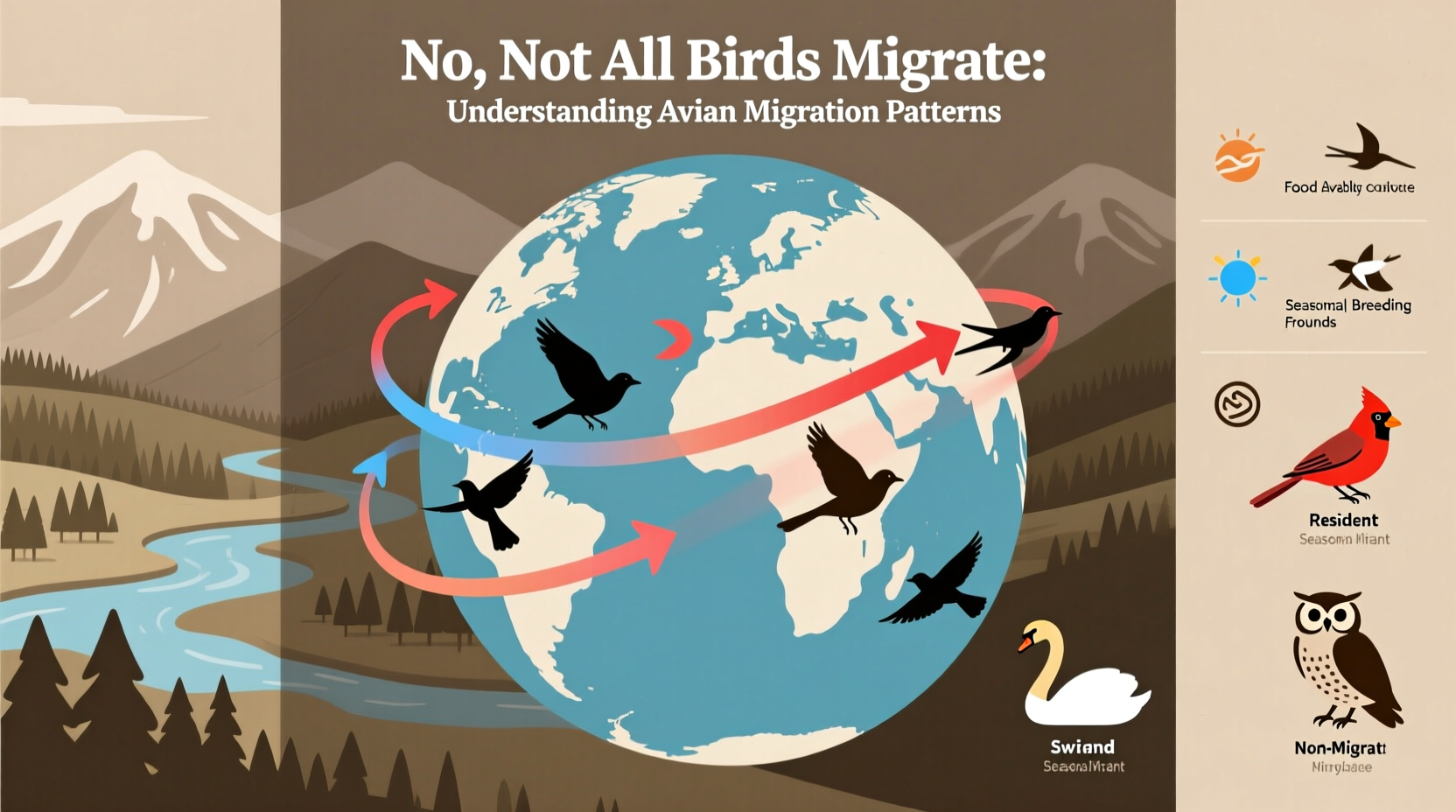

Not all birds migrate; in fact, only about 40% of bird species worldwide engage in seasonal migration. This means that while many birds do undertake long-distance journeys between breeding and wintering grounds each year—a behavior often referred to as seasonal bird migration patterns—a significant majority remain in the same region year-round. Whether a bird migrates depends on factors such as species, geographic location, food availability, and climate conditions. Understanding which birds migrate and why helps both amateur birdwatchers and conservationists better appreciate avian diversity and plan effective observation strategies.

The Biological Basis of Bird Migration

Bird migration is a complex behavior driven by evolutionary adaptations to maximize survival and reproductive success. Migratory birds typically travel from temperate or polar regions, where summers offer abundant food and nesting opportunities, to warmer climates during winter when resources become scarce. These movements can span thousands of miles—some Arctic Terns fly over 40,000 miles annually between the Arctic and Antarctic.

Migration is primarily triggered by changes in daylight length (photoperiod), which influences hormonal activity. As days shorten in autumn, birds experience physiological changes: fat reserves increase, restlessness (known as Zugunruhe) sets in, and orientation systems activate. Many species use celestial cues, Earth's magnetic field, and even olfactory signals to navigate with astonishing precision.

However, not all birds need to migrate. Species living in tropical zones, where temperatures and food supplies remain relatively stable throughout the year, often show little to no migratory behavior. Similarly, some temperate-zone birds, like cardinals or chickadees, have adapted to survive cold winters by switching diets, caching food, or relying on human-provided feeders.

Types of Migration Patterns Among Birds

Bird migration isn't a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Ornithologists classify migration into several types based on distance, timing, and consistency:

- Complete Migration: All members of a population leave their breeding grounds for winter.

- Partial Migration: Only some individuals (often younger males or non-breeding birds) migrate, while others stay behind.

- Leapfrog Migration: Northern populations migrate farther south than southern ones, effectively 'leapfrogging' over them.

- Irruptive Migration: Irregular movements driven by food shortages rather than seasonality—seen in species like crossbills or snowy owls.

For example, American Robins exhibit partial migration: northern populations head south in winter, but many southern robins remain resident year-round. This variability underscores the importance of regional knowledge when observing local birdlife.

Why Don’t All Birds Migrate? Ecological and Evolutionary Factors

The decision to migrate involves a cost-benefit analysis shaped by evolution. Migration demands immense energy, exposes birds to predators and harsh weather, and increases mortality risk. For many species, staying put is safer and more efficient.

Non-migratory birds often possess traits that enhance winter survival:

- Diet flexibility (e.g., switching from insects to berries or seeds)

- Ability to store food (like nuthatches hiding nuts under bark)

- Thermoregulatory adaptations (fluffing feathers, entering torpor at night)

- Social behaviors (flocking for warmth and predator detection)

In urban environments, where food sources like bird feeders and waste are reliable, even traditionally migratory species may shorten or abandon migrations. European Blackbirds in cities, for instance, are increasingly sedentary compared to their rural counterparts.

Geographic and Regional Differences in Migration Behavior

Migration patterns vary significantly across continents and ecosystems. In North America, strong latitudinal gradients create clear seasonal contrasts, prompting extensive migrations among warblers, waterfowl, and raptors. By contrast, in equatorial regions, where seasons are less defined, most birds are non-migratory.

Here’s a breakdown of migration prevalence by region:

| Region | % Migratory Species | Examples of Migratory Birds | Common Resident Birds |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | ~60% | Barn Swallow, Canada Goose, Broad-winged Hawk | Northern Cardinal, Carolina Wren, Downy Woodpecker |

| Europe | ~50% | Swainson's Thrush, European Robin (some pop.), White Stork | Great Tit, Eurasian Jay, House Sparrow |

| Tropical Africa | ~20% | European Bee-eater, Abdim's Stork | African Grey Parrot, Superb Starling, Hornbill |

| Australia | ~30% | Freckled Duck, Swift Parrot | Kookaburra, Rainbow Lorikeet, Emu |

These differences highlight the importance of location-specific research and citizen science efforts like eBird in tracking movement trends.

Climate Change and Shifting Migration Patterns

One of the most pressing issues in modern ornithology is how climate change affects bird migration. Warmer winters and altered food availability are causing shifts in timing (phenology) and range. Some species now migrate later in fall or return earlier in spring. Others, like the Mourning Dove, are expanding their ranges northward and becoming permanent residents in areas where they once only appeared seasonally.

While these changes may benefit certain birds in the short term, they also pose risks. Early arrivals may face unseasonal cold snaps, and mismatches between hatching times and peak insect abundance can reduce chick survival. Long-term monitoring is essential to understand these dynamics.

How to Observe Migration: Practical Tips for Birdwatchers

If you're interested in witnessing bird migration firsthand, here are actionable steps to enhance your experience:

- Know When Peak Migration Occurs: In North America, spring migration runs March–May, with April being prime time. Fall migration spans August–November, peaking in September–October.

- Visit Key Stopover Sites: Coastal wetlands, lakeshores, and mountain ridges concentrate migrating birds. Places like Cape May (NJ), Point Pelee (ON), and Monterey Bay (CA) are renowned hotspots.

- Use Technology: Apps like Merlin Bird ID and eBird provide real-time sightings and migration forecasts. The Cornell Lab’s Barometer of Spring tracks first sightings of key species.

- Watch at Dawn: Most songbirds migrate at night and land at sunrise. Early morning walks yield the highest diversity.

- Listen for Nocturnal Flight Calls: Using a parabolic microphone or even a smartphone app, you can detect high-altitude calls of migrating thrushes and warblers after dark.

Even if you live in an area without large-scale migrations, noting subtle changes in your backyard feeder visitors throughout the year can reveal local movement patterns.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About Bird Migration

Several myths persist about bird migration that can mislead both casual observers and educators:

- Misconception: All small birds must migrate because they can’t survive cold.

Truth: Chickadees and kinglets endure subzero temperatures using metabolic and behavioral adaptations. - Misconception: Birds migrate because it gets cold.

Truth: It’s mainly about food scarcity, not temperature. Hummingbirds leave before frost arrives, following nectar and insect declines. - Misconception: Migration is always southward.

Truth: In the Southern Hemisphere, birds migrate northward. Some species move altitudinally—down mountains in winter—without changing latitude. - Misconception: Once a bird leaves, it won’t return until next year.

Truth: Some species make multiple trips or partial returns mid-winter if conditions improve.

Conservation Implications of Migration Knowledge

Understanding which birds migrate—and which don’t—is crucial for habitat protection. Migratory species require safe passage across international borders, making coordinated conservation vital. Threats like light pollution (which disorients nocturnal migrants), wind turbines, and habitat loss along flyways endanger millions of birds annually.

Organizations like Partners in Flight and GCBO (Gulf Coast Bird Observatory) work to protect critical stopover habitats. Individuals can help by turning off lights during peak migration nights (Lights Out programs), keeping cats indoors, and planting native vegetation that supports both resident and transient species.

Conclusion: A Diverse World of Avian Movement

To reiterate: no, not all birds migrate. Migration is just one survival strategy among many. From the globe-trotting Arctic Tern to the steadfast Northern Cardinal singing in a snowy backyard, birds exemplify nature’s adaptability. Recognizing this diversity enriches our understanding of ecology and deepens our connection to the natural world. Whether you’re tracking swallows heading south or enjoying year-round chickadee visits, every observation contributes to a broader picture of avian life.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds fly south for the winter?

No. Only migratory species do, and even then, “south” depends on hemisphere. Many birds stay in place year-round. - What percentage of birds actually migrate?

About 40% of the world’s ~10,000 bird species are migratory, though rates vary by region. - Can a bird decide not to migrate one year?

Yes, especially in mild winters or areas with reliable food sources like feeders or urban waste. - Are there birds that migrate east or west instead of north-south?

Most migrations are latitudinal, but some seabirds and island species move longitudinally based on oceanic productivity. - How can I tell if a bird in my yard is migratory?

Check seasonal occurrence data via eBird or field guides. Sudden appearances in spring/fall or absence in certain months suggest migration.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4