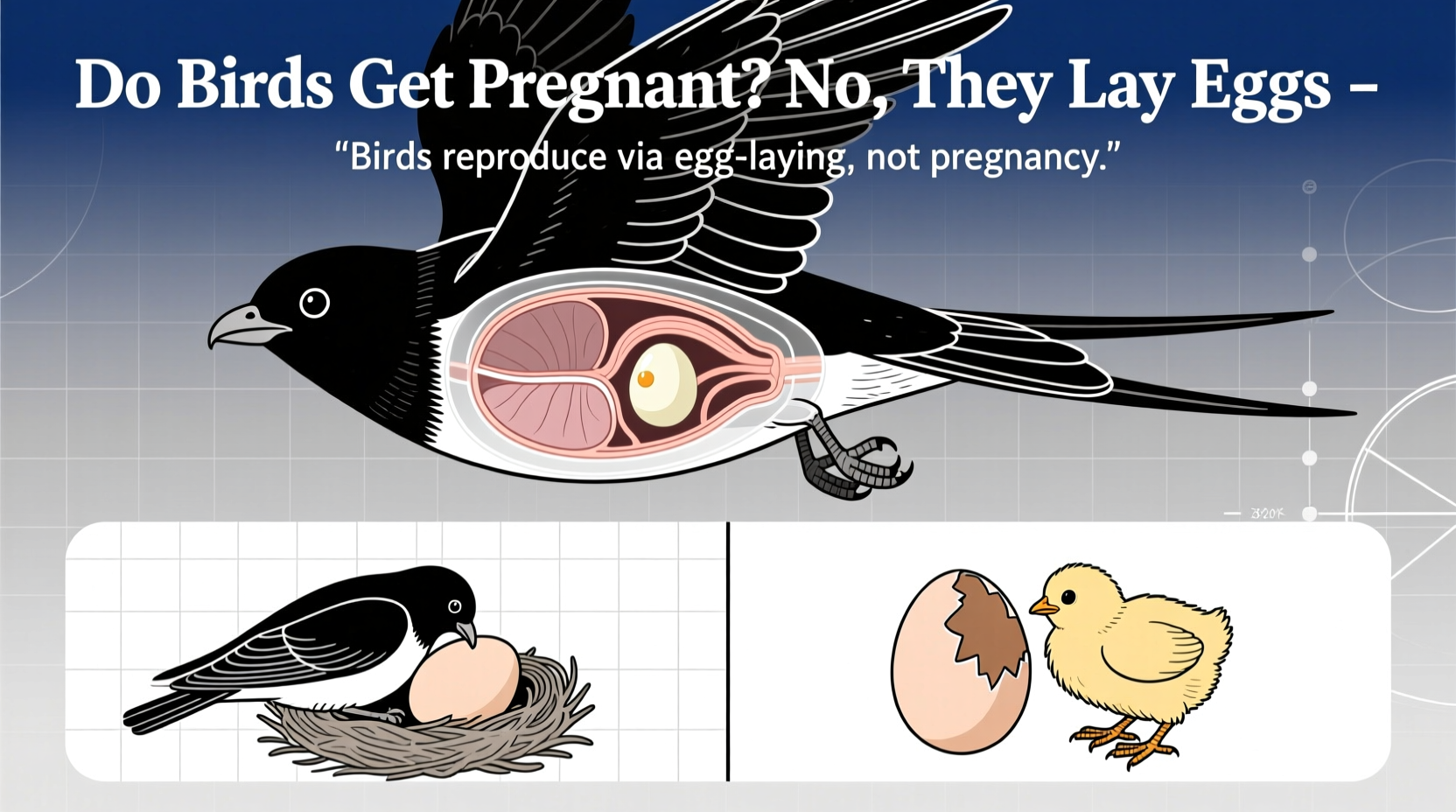

No, birds do not get pregnant in the way mammals do. While the phrase do birds get pregnant might seem logical when thinking about animal reproduction, the biological reality is quite different. Birds reproduce through egg-laying, a process that begins with internal fertilization but does not involve pregnancy as seen in humans or other mammals. This fundamental distinction reflects the evolutionary divergence between avian and mammalian species. Understanding this difference not only clarifies a common misconception but also opens the door to appreciating the unique reproductive strategies birds have developed over millions of years.

How Do Birds Reproduce If They Don’t Get Pregnant?

Bird reproduction centers around the production and laying of eggs rather than gestation inside the mother’s body. After mating, sperm from the male fertilizes the egg inside the female’s reproductive tract. Once fertilized, the egg is encased in a protective shell made primarily of calcium carbonate before being laid. Unlike mammals, where embryos develop internally and receive nutrients directly from the mother via the placenta, bird embryos develop outside the body, relying on the yolk and albumen within the egg for nourishment.

This method of reproduction—oviparity—is shared by all bird species, from hummingbirds to ostriches. The entire process, from ovulation to laying, can take anywhere from 24 hours in small songbirds to several days in larger birds like eagles or albatrosses. Most birds lay one egg per day until their clutch is complete, although some species may skip days depending on environmental conditions or energy availability.

The Biological Process Behind Bird Egg Formation

To fully understand why birds don’t get pregnant, it helps to examine the avian reproductive system. Female birds typically have only one functional ovary (usually the left), which releases yolks into the oviduct. As the yolk travels down the oviduct, layers are added: first the albumen (egg white), then membranes, and finally the hard outer shell in the uterus (also called the shell gland).

Fertilization occurs at the top of the oviduct if sperm is present. However, females can store sperm for days or even weeks, allowing them to fertilize multiple eggs from a single mating event. After the shell forms, the egg moves to the cloaca and is laid. There is no prolonged developmental phase inside the mother’s body, which means there is no pregnancy in the mammalian sense.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Oviparous (egg-laying) | Viviparous (live birth) |

| Internal Fertilization | Yes | Yes |

| Embryo Development Location | Outside body (in egg) | Inside uterus |

| Nutrient Source for Embryo | Yolk and albumen | Placenta |

| Pregnancy Period | None | Varies by species (e.g., 9 months in humans) |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Pregnancy

One reason people ask do birds get pregnant is because they observe female birds appearing larger before laying eggs. This temporary swelling is due to the development of yolks and the formation of the eggshell, not fetal growth. Similarly, nesting behavior—such as gathering materials or guarding a site—can be mistaken for signs of pregnancy, much like human nesting instincts before childbirth.

Another source of confusion comes from pets like parrots or backyard chickens. Owners may notice behavioral changes or physical bloating and assume their bird is “pregnant.” In reality, these symptoms often indicate an impending egg-lay or, in some cases, health issues such as egg binding, a potentially life-threatening condition where an egg becomes stuck in the oviduct.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Bird Eggs and Reproduction

Beyond biology, bird reproduction holds deep symbolic meaning across cultures. Eggs are nearly universal symbols of new life, renewal, and potential. In many traditions, especially during spring festivals like Easter, decorated eggs represent resurrection and rebirth—concepts closely tied to avian hatching cycles.

In mythology, birds themselves often serve as messengers between worlds. The phoenix rising from ashes echoes the idea of regeneration, while storks delivering babies reflect cultural narratives linking birds to human fertility. Though biologically inaccurate, these stories persist because they tap into observable patterns: birds return with the seasons, build nests, lay eggs, and nurture young—all visible markers of cyclical creation.

Indigenous belief systems also emphasize harmony with nature, viewing bird nesting and egg-laying as part of ecological balance. For example, some Native American tribes see the robin’s arrival as a sign that the earth is ready to support new life, blending seasonal observation with spiritual interpretation.

Observing Bird Reproduction in the Wild: A Guide for Birdwatchers

For amateur and experienced birders alike, witnessing avian reproduction offers a rewarding glimpse into natural behaviors. Knowing what to look for—and when—can enhance your观鸟 experience (birdwatching). Here are practical tips:

- Timing matters: Most temperate-zone birds breed in spring and early summer when food is abundant. Start watching for courtship displays as early as late winter.

- Look for nest-building: Species like robins, swallows, and cardinals construct distinctive nests. Robins use mud and grass in trees or ledges; barn swallows create cup-shaped nests from saliva and mud under eaves.

- Listen for changes in song: Male birds sing more frequently during mating season to attract mates and defend territory.

- Observe feeding behavior: Once chicks hatch, parents make repeated trips to feed them. Following an adult bird carrying insects may lead you to a hidden nest.

- Respect distance: Never approach or touch a nest. Disturbance can cause abandonment or attract predators.

Use binoculars or spotting scopes to observe without intrusion. Consider keeping a journal to record species, nesting locations, clutch sizes, and fledging dates. Over time, this data contributes to citizen science efforts like NestWatch, run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Differences Among Bird Species in Reproductive Strategies

While all birds lay eggs, their reproductive tactics vary widely. These adaptations reflect habitat, predation pressure, and resource availability.

Altricial vs. Precocial Chicks: Some birds, like songbirds, hatch blind and helpless (altricial), requiring intensive parental care. Others, such as ducks and quail, produce precocial young that can walk, swim, and feed themselves shortly after hatching.

Clutch Size: Smaller birds tend to lay more eggs per clutch. A house wren may lay 5–8 eggs, while large raptors like bald eagles usually lay only 1–3. Island-dwelling birds often have smaller clutches, possibly due to limited resources.

Breeding Frequency: Many songbirds raise multiple broods per year, whereas larger birds like albatrosses may breed only once every two years, investing heavily in each chick.

Nesting Locations: From cliff ledges to tree cavities to ground nests, birds exploit diverse environments. Cavity-nesters like woodpeckers and bluebirds rely on holes in trees or nest boxes, making them vulnerable to competition and habitat loss.

Human Impact on Bird Reproduction

Urbanization, climate change, and pesticide use all affect avian reproductive success. Light pollution can disrupt mating signals and migration timing. Pesticides like DDT historically caused thinning of eggshells, leading to widespread reproductive failure in raptors—a key factor in the decline of peregrine falcons and bald eagles in the mid-20th century.

Today, conservationists work to mitigate these threats. Installing nest boxes helps compensate for lost tree cavities. Protecting wetlands supports waterfowl breeding. Reducing plastic waste prevents ingestion and entanglement risks for chicks.

Climate shifts are altering breeding schedules. Some European migratory birds now arrive earlier in spring, but if insect emergence doesn’t match, chick survival drops. Citizen science projects help track these mismatches, informing policy and habitat management.

What Should You Do If You Find a Bird Egg?

Finding a lone egg can trigger curiosity or concern. However, the best course of action is usually to leave it undisturbed. Most wild bird eggs are protected by laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in the U.S., making it illegal to possess them without a permit.

If you suspect an egg has fallen from a nest, do not attempt to return it yourself. Handling can transfer human scent, increasing the risk of parental rejection. Additionally, improper placement may harm developing embryos. Instead, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator who can assess viability and determine appropriate steps.

For domesticated birds like chickens, unfertilized eggs are safe to eat. Fertilized eggs intended for hatching require incubation at consistent temperatures (around 99.5°F) and humidity levels for 21 days (for chickens) or longer for other species.

FAQs About Bird Reproduction

- Can you tell if a bird egg is fertilized?

- Yes, through candling—a technique using a bright light to view the interior. After a few days of incubation, a fertilized egg will show blood vessels and embryo development.

- Do male birds help incubate eggs?

- In many species, yes. Male emperor penguins incubate a single egg on their feet for months. In songbirds like robins, males may guard the territory while females sit on the nest.

- How long do bird eggs take to hatch?

- Hatching time varies: 12–14 days for small songbirds, 21 days for chickens, 35 days for mallards, and up to 80 days for large seabirds like albatrosses.

- Why don’t birds give live birth?

- Evolutionarily, egg-laying allows greater mobility during reproduction. Carrying developing young internally would add weight, impairing flight—an essential adaptation for most birds.

- Are there any birds that give birth to live young?

- No known bird species gives live birth. All extant birds are oviparous. Even flightless birds like kiwis and ostriches lay eggs.

In summary, the question do birds get pregnant stems from a desire to understand how birds bring new life into the world. The answer lies not in pregnancy, but in the intricate and elegant process of egg formation, laying, and incubation. By studying both the science and symbolism of avian reproduction, we gain deeper insight into the lives of these remarkable creatures and our shared connection to the rhythms of nature.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4