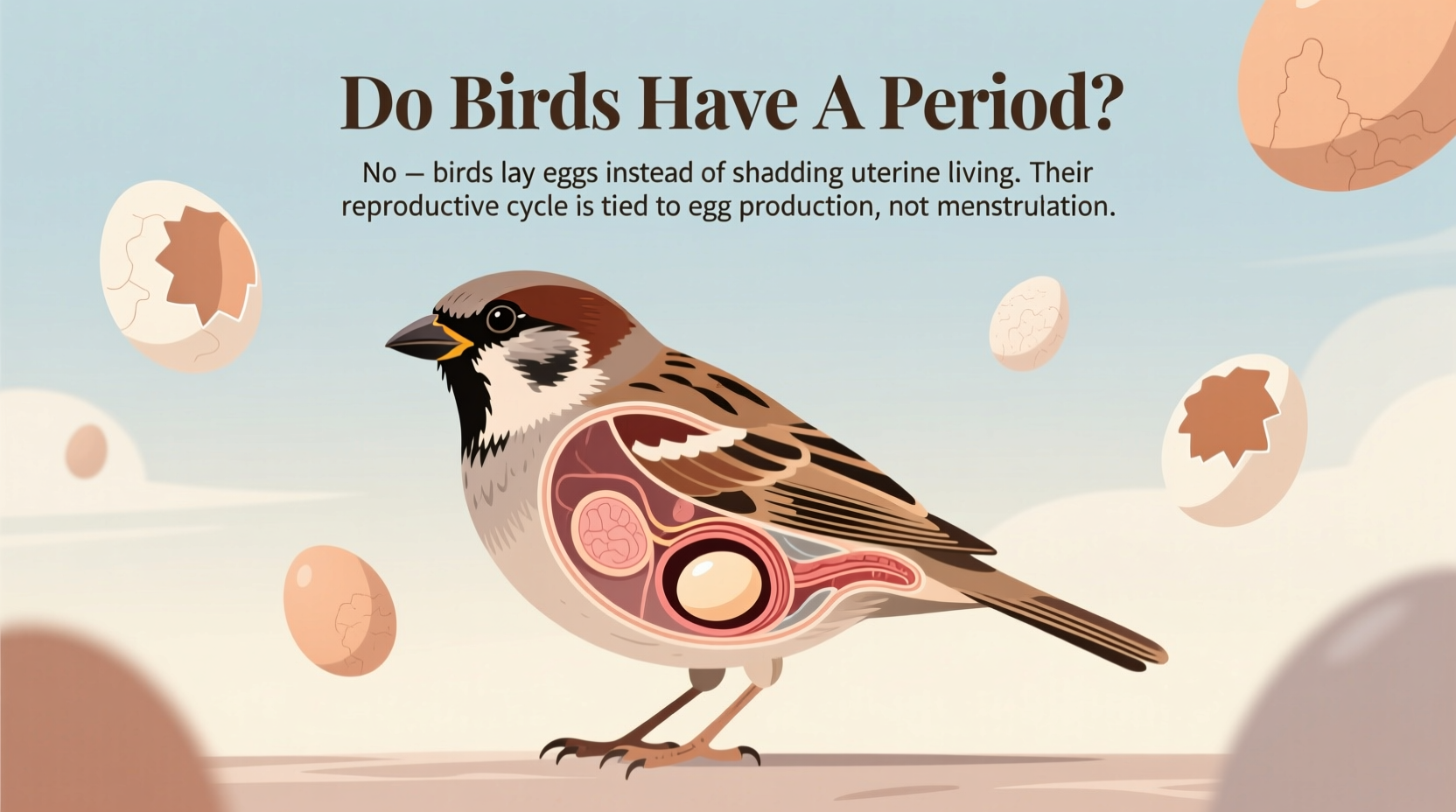

No, birds do not have a period. Unlike mammals, birds lack a uterus and do not undergo a menstrual cycle, which means there is no shedding of the uterine lining—commonly known as a period. This fundamental difference in reproductive biology answers the frequently asked question: do birds have a period? The short and definitive answer is no. Instead of menstruating, female birds ovulate and lay eggs, often seasonally, as part of their natural reproductive process. Understanding this distinction helps clarify common misconceptions about avian physiology and highlights the unique ways birds reproduce compared to mammals.

Understanding Bird Reproduction: A Biological Overview

Birds are oviparous animals, meaning they reproduce by laying eggs that develop and hatch outside the mother’s body. This is in stark contrast to most mammals, which are viviparous—giving birth to live young after internal development. The absence of a menstrual cycle in birds stems from their evolutionary path, which diverged significantly from that of mammals millions of years ago.

In female mammals, including humans, the menstrual cycle prepares the body for potential pregnancy each month. If fertilization does not occur, the thickened uterine lining is shed through bleeding—what we call a period. Birds, however, do not build up such a lining. Instead, when a female bird is ready to reproduce, her ovary releases a yolk (the ovum), which then travels through the oviduct where layers such as albumen (egg white), membranes, and the shell are added over approximately 24 hours before being laid.

This process is regulated by hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, similar to those in mammals, but the outcome is entirely different. There is no cyclic shedding of tissue; instead, egg production is typically seasonal and triggered by environmental cues like daylight length, temperature, and food availability.

How Female Birds Prepare for Egg Laying

The reproductive system of a female bird is highly specialized. Most female birds have only one functional ovary—the left—and a single oviduct. During the breeding season, this ovary enlarges dramatically and begins producing yolks. Each yolk is essentially an unfertilized egg cell, and if mating has occurred, it may be fertilized in the infundibulum (the first section of the oviduct) shortly after ovulation.

As the yolk moves through the oviduct, it undergoes several transformations:

- Magnum: Egg white (albumen) is added.

- Isthmus: Inner and outer shell membranes form.

- Uterus (shell gland): The hard calcium carbonate shell is deposited over 18–20 hours.

- Vagina: The fully formed egg passes out of the body during oviposition.

This entire process takes about 24–26 hours in most bird species, which explains why many birds lay one egg per day during clutch formation. Once the full clutch is laid, incubation usually begins, either immediately or after the last egg, depending on the species.

Seasonality and Environmental Triggers

Birds are generally seasonal breeders, meaning their reproductive activity is closely tied to environmental conditions. Daylight length (photoperiod) is one of the most critical factors influencing hormonal changes that initiate ovulation. As days grow longer in spring, increased light stimulates the hypothalamus in the bird’s brain, triggering the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which in turn activates the pituitary gland to secrete follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

These hormones stimulate ovarian development and egg production. In wild birds, this ensures that chicks hatch during times of abundant food and favorable weather. Captive birds, especially pet parrots, can sometimes become reproductively active year-round due to artificial lighting, warmth, and consistent food supply—leading to health issues like chronic egg-laying.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Menstruation

One reason people ask do birds have a period is because they observe behaviors or physical signs that seem similar to menstruation. For example, some birds may exhibit blood-tinged droppings or vaginal bleeding during egg-laying, especially if there’s an injury or egg-binding. However, this is not a menstrual period—it’s a sign of trauma or pathology.

Another misconception arises from observing pet birds becoming broody or laying eggs without a mate. While this might resemble a “cycle,” it’s actually a hormonally driven behavior linked to environmental stimuli, not a monthly reproductive reset like in primates. Birds do not experience cyclical hormonal fluctuations in the same way humans do; their reproductive activity is more episodic and event-driven.

Additionally, since birds don’t have external genitalia like mammals, their reproductive processes are internal and less visible, contributing to confusion. But scientifically, the answer remains clear: birds do not menstruate.

Comparative Anatomy: Birds vs. Mammals

To further clarify why birds don’t have periods, it helps to compare their anatomy with that of mammals. The table below outlines key differences:

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Strategy | Oviparous (lay eggs) | Viviparous (live birth) or oviparous (monotremes) |

| Menstrual Cycle | Absent | Present in most primates, some bats |

| Uterus | No true uterus; has a shell gland | Yes, with endometrial lining |

| Egg Development | External after laying | Internal (except monotremes) |

| Ovarian Function | Single functional ovary in most species | Two ovaries |

| Hormonal Regulation | Photoperiod-driven, seasonal | Cyclical, monthly in many species |

As shown, the structural and functional differences make menstruation biologically unnecessary and impossible in birds.

Implications for Bird Owners and Avian Health

For pet bird owners, understanding that birds do not have periods is crucial for recognizing abnormal symptoms. Any bleeding from the vent (the shared opening for digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts) should be considered a medical emergency. Possible causes include:

- Egg binding (a life-threatening condition where an egg gets stuck)

- Reproductive tract infection or tumor

- Trauma during mating or egg-laying

- Calcium deficiency leading to weak muscles and poor eggshell formation

Chronic egg-laying—a condition where a female bird lays excessive clutches without a mate—is another concern in captivity. It’s not a normal cycle but a behavioral and hormonal issue often triggered by environmental factors. Solutions include adjusting light exposure, removing nesting materials, and consulting an avian veterinarian for possible hormone therapy.

Observing Bird Reproduction in the Wild

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, understanding avian reproduction enhances field observations. During spring and early summer, you’re likely to see courtship displays, nest-building, feeding of young, and territorial behaviors—all signs of active breeding. Knowing that these events are tied to seasonal rhythms rather than monthly cycles helps interpret timing and frequency.

Some species, like albatrosses, breed only every other year, while others, such as house sparrows, may raise multiple broods annually. Observing egg-laying patterns, incubation duration, and fledging success offers insight into population health and ecological conditions.

If you find a bird egg outside a nest, it’s important not to assume it’s abandoned. Many birds lay one egg per day, so partial clutches are normal. Only intervene if the egg is cracked, cold, or clearly in danger—otherwise, leave it undisturbed.

Evolutionary Perspective: Why Don’t Birds Menstrate?

From an evolutionary standpoint, menstruation is rare in the animal kingdom. Only a few species—including humans, some primates, certain bats, and elephant shrews—experience true menstruation. Most mammals reabsorb the uterine lining if pregnancy doesn’t occur.

Birds evolved a completely different strategy. By investing energy into producing nutrient-rich eggs with protective shells, they maximize offspring survival in variable environments. The cost of building and laying an egg is high, so birds avoid wasting resources on non-viable embryos. Instead of preparing the body monthly for pregnancy, birds time reproduction precisely to environmental conditions, reducing energy expenditure and increasing reproductive efficiency.

FAQs About Birds and Reproduction

Q: Do female birds bleed when they lay eggs?

A: Not normally. Minor spotting can occur due to strain or minor tearing, but significant bleeding is a sign of illness or injury and requires veterinary attention.

Q: Can birds lay eggs without mating?

A: Yes. Unfertilized eggs are common in female birds, especially in captivity. These are analogous to chicken eggs sold for consumption.

Q: How often do birds lay eggs?

A: It depends on the species. Many wild birds lay one egg per day until the clutch is complete, then begin incubating. Some pet birds may lay eggs year-round if stimulated by environment.

Q: Do birds have periods like dogs or cats?

A: No. Dogs and cats do not menstruate like humans either. They have estrous cycles, where the uterine lining is reabsorbed if no pregnancy occurs. Birds do not have either a menstrual or estrous cycle.

Q: Is egg-laying painful for birds?

A: Egg-laying is a natural process and typically not painful, though complications like egg binding can cause severe distress. Signs of pain include lethargy, straining, fluffed feathers, and inability to perch.

In conclusion, the question do birds have a period reflects a common curiosity about animal biology. The answer lies in understanding the fundamental differences between avian and mammalian reproduction. Birds do not menstruate; instead, they lay eggs through a highly efficient, seasonally regulated process that has evolved to suit their ecological niches. Whether you're a bird owner, researcher, or enthusiast, appreciating these distinctions enriches your knowledge and promotes better care and conservation of these remarkable creatures.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4