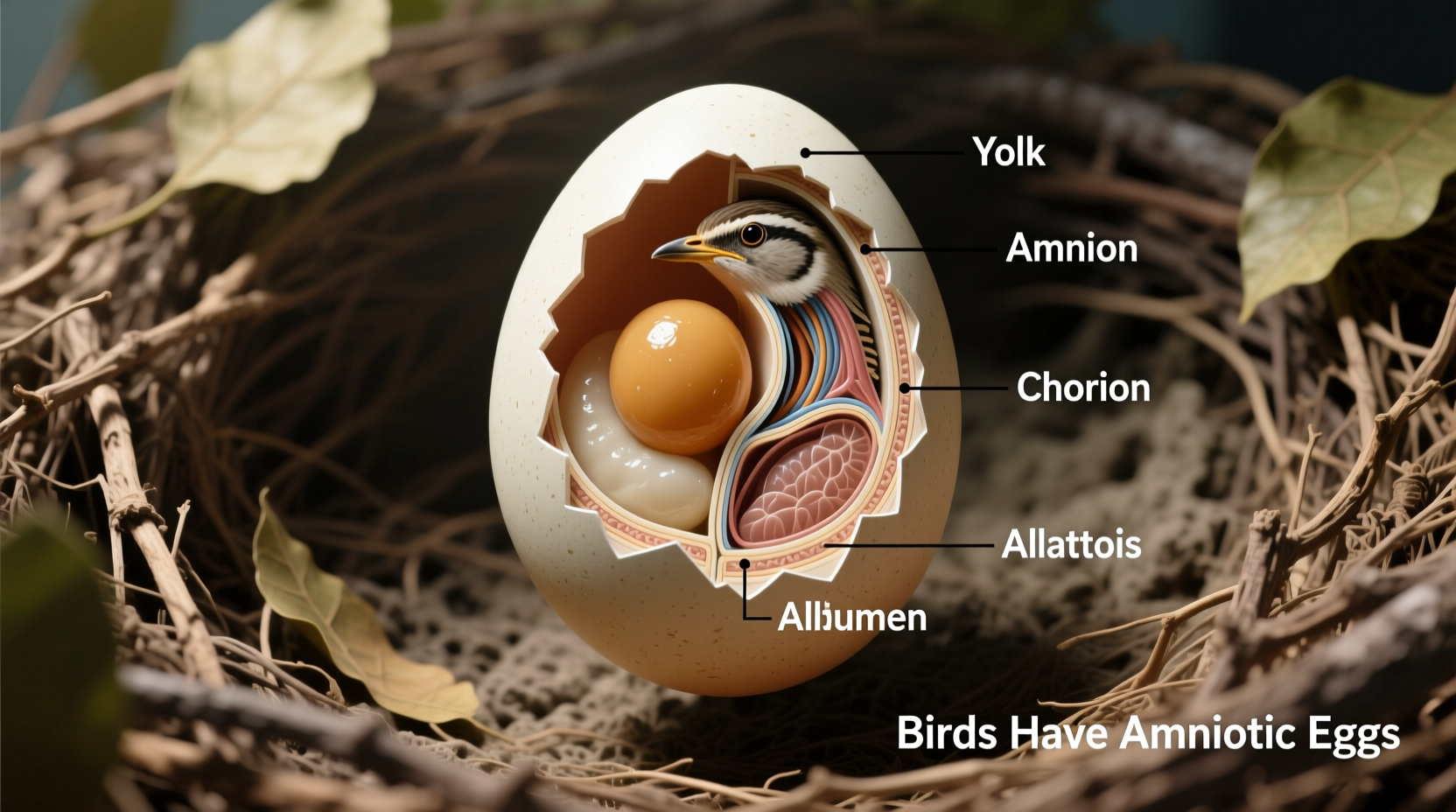

Yes, birds do have amniotic eggsâa defining feature that places them within the larger group of amniotes, which includes reptiles and mammals. This biological adaptation allows bird embryos to develop on land, protected by a series of specialized membranes, including the amnion, chorion, allantois, and yolk sac. The presence of amniotic eggs in birds is a key evolutionary milestone that enabled vertebrates to colonize terrestrial environments far from water sources. Understanding do birds have amniotic eggs not only clarifies their reproductive biology but also highlights their deep evolutionary ties to other land-dwelling vertebrates.

What Are Amniotic Eggs and Why Do They Matter?

Amniotic eggs are a critical innovation in vertebrate evolution. Unlike amphibians, which lay jelly-like eggs in water, animals with amniotic eggs can reproduce on dry land. These eggs contain several extraembryonic membranes that support the developing embryo:

- Amnion: A fluid-filled sac that cushions the embryo.

- Chorion: Surrounds the entire contents and aids in gas exchange. \li>Allantois: Manages waste storage and contributes to respiration.

- Yolk sac: Provides nutrition from stored yolk.

- Shell: A leathery or calcified outer layer that prevents desiccation while allowing oxygen and carbon dioxide to pass through.

In birds, the eggshell is typically hard and calcified, offering strong protection against physical damage and microbial invasion. This structure supports extended incubation periods, during which the chick develops fully before hatching.

Evolutionary Origins of Amniotic Eggs in Birds

Birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, a lineage that itself descended from early reptiles. Fossil evidence shows that amniotic reproduction predates birds by hundreds of millions of years. The first true amniotes appeared around 310â350 million years ago during the Carboniferous period, long before dinosaurs dominated the Earth.

The transition to amniotic eggs was pivotal because it freed reproduction from aquatic constraints. Early tetrapods like amphibians still require water for spawning, but amniotesâincluding birdsâcan lay eggs in arid environments. This adaptability contributed significantly to the global distribution of birds today.

Modern birds retain the fundamental amniotic egg structure seen in reptiles, though with modifications such as a more rigid shell and higher metabolic demands due to endothermy (warm-bloodedness). These traits reflect both shared ancestry and unique avian adaptations.

How Bird Eggs Differ from Other Amniotes

While birds, reptiles, and some mammals (like monotremes) all produce amniotic eggs, there are notable differences in structure and function:

| Feature | Birds | Reptiles | Monotreme Mammals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggshell Type | Hard, calcified | Leathery or flexible | Soft, parchment-like |

| Incubation Environment | Nests, often warmed by parents | Buried or hidden, environment-dependent | Incubated in pouch or nest |

| Yolk Size | Large (complete nutrition) | Moderate to large | Very large |

| Parental Care | High (brooding, feeding) | Limited to none | Moderate (milk provision after hatch) |

| Hatchling Development | Precocial or altricial | Generally independent at birth | Underdeveloped, requires care |

These variations illustrate how the basic amniotic plan has been fine-tuned across lineages. For example, birds invest heavily in parental care, which correlates with higher survival rates despite fewer offspring per clutch.

Biological Advantages of Amniotic Eggs in Avian Species

The amniotic egg provides birds with several reproductive advantages:

- Terrestrial Independence: No need for standing water to spawn, enabling nesting in trees, cliffs, deserts, and urban areas.

- Embryo Protection: The multi-layered membrane system shields against dehydration, pathogens, and mechanical shock.

- Efficient Gas Exchange: The porous shell allows oxygen in and carbon dioxide out without compromising moisture retention.

- Nutritional Self-Sufficiency: The yolk sustains the embryo throughout development, eliminating the need for external feeding.

These features make bird reproduction highly adaptable. From penguins incubating eggs on Antarctic ice to songbirds nesting in suburban backyards, the amniotic egg supports life in extreme and variable conditions.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bird Eggs

Beyond biology, bird eggs carry rich symbolic meanings across cultures. In many traditions, eggs represent renewal, fertility, and the potential for new life. The Easter egg, for instance, blends pre-Christian spring rituals with Christian symbolism of resurrection. Similarly, in Persian culture, decorated eggs are part of Nowruz celebrations marking the New Year and rebirth of nature.

In art and mythology, bird eggs often symbolize creation. Ancient Egyptian cosmology described the world emerging from a âcosmic egg,â sometimes laid by a celestial bird. In Chinese folklore, the primordial giant Pangu is said to have formed from an egg floating in chaos.

Even in modern psychology, Carl Jung interpreted the egg as an archetype of wholeness and transformation. Thus, understanding do birds have amniotic eggs connects not just to science but to enduring human narratives about origin and possibility.

Observing Amniotic Eggs in Nature: Tips for Birdwatchers

For bird enthusiasts, studying eggs offers insight into species behavior, ecology, and conservation status. However, observing nests requires responsibility and legal awareness:

- Never disturb active nests: In many countries, including the U.S. under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, it's illegal to touch or remove bird eggs without a permit.

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Observe from a distance to avoid stressing parent birds or attracting predators.

- Record details ethically: Note egg color, size, shape, and nesting locationâbut donât publicize sensitive locations online.

- Join citizen science projects: Programs like NestWatch (run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology) allow contributors to submit data while following strict ethical guidelines.

Learning to identify eggs by species can deepen your appreciation of avian diversity. For example, robins lay distinctive blue eggs, while barn owls produce pure white ones. Egg shape also varies: shorebirds often have conical eggs that resist rolling off cliffs, whereas cavity-nesters tend to have more spherical eggs.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Reproduction

Several myths persist about bird eggs and reproduction:

- Myth: All birds lay eggs with hard shells. While most do, some species (like certain kiwis) have thinner, more flexible shells relative to body size.

- Myth: If you touch an egg, the parents will reject it. Most birds have a poor sense of smell and wonât abandon eggs simply because theyâve been handledâthough handling should still be avoided to prevent disease or predator scent transfer.

- Myth: Birds only lay eggs in spring. While breeding seasons peak in spring in temperate zones, tropical birds may breed year-round, and some species (like doves) can nest multiple times annually.

- Myth: Amniotic eggs mean live birth is impossible. Actually, some amniotes (like most mammals) have evolved viviparity. But birds universally rely on external egg-laying (oviparity).

Clarifying these points helps ensure accurate public understanding of avian biology.

How Climate and Environment Affect Egg Development

Although amniotic eggs are well-protected, environmental factors still influence hatching success:

- Temperature: Most bird eggs require consistent warmth (typically 95â100°F) for proper development. Too cold slows metabolism; too hot can be lethal.

- Humidity: Low humidity increases water loss through the shell, potentially causing dehydration. High humidity may promote mold growth.

- Pollution: Contaminants like DDT historically caused eggshell thinning in raptors, leading to population declines. Though banned in many regions, similar chemicals remain a concern.

- Nest Placement: Birds choose microhabitats carefullyâtree cavities, dense shrubs, or shaded ground sitesâto buffer eggs from temperature extremes.

Climate change now poses new challenges. Shifts in seasonal timing can desynchronize egg-laying with food availability, reducing chick survival. Researchers monitor these trends closely through long-term studies.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds lay amniotic eggs?

- Yes, all bird species produce amniotic eggs. This is a universal trait among avians and reflects their evolutionary heritage as amniotes.

- Are bird eggs the same as reptile eggs?

- They share core structures (amnion, chorion, etc.), but bird eggs typically have harder, calcified shells compared to the leathery shells of most reptile eggs.

- Can amniotic eggs survive outside the body?

- Yes, one of the key features of amniotic eggs is their ability to develop externally in terrestrial environments, thanks to protective membranes and shells.

- Do any mammals lay amniotic eggs?

- Yesâmonotremes like the platypus and echidna lay amniotic eggs, making them unique among mammals.

- Why donât birds give live birth?

- Evolutionarily, birds retained oviparity (egg-laying) as it reduces maternal energy burden during gestation and allows safer embryonic development in a controlled external environment.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4