Do birds have belly buttons? The short answer is no—birds do not have belly buttons in the way mammals do. While the concept of a belly button or navel is familiar to most people as the scar left after the umbilical cord detaches at birth, this structure is unique to placental mammals. Since birds lay eggs and do not rely on a placenta or umbilical cord during embryonic development, they never form a true belly button. This fundamental difference in reproductive biology explains why you’ll never spot a navel on a robin, eagle, or hummingbird. So, when asking do birds have belly buttons, the biological reality points to a clear 'no.'

The Biology Behind Bird Development: Why No Belly Button?

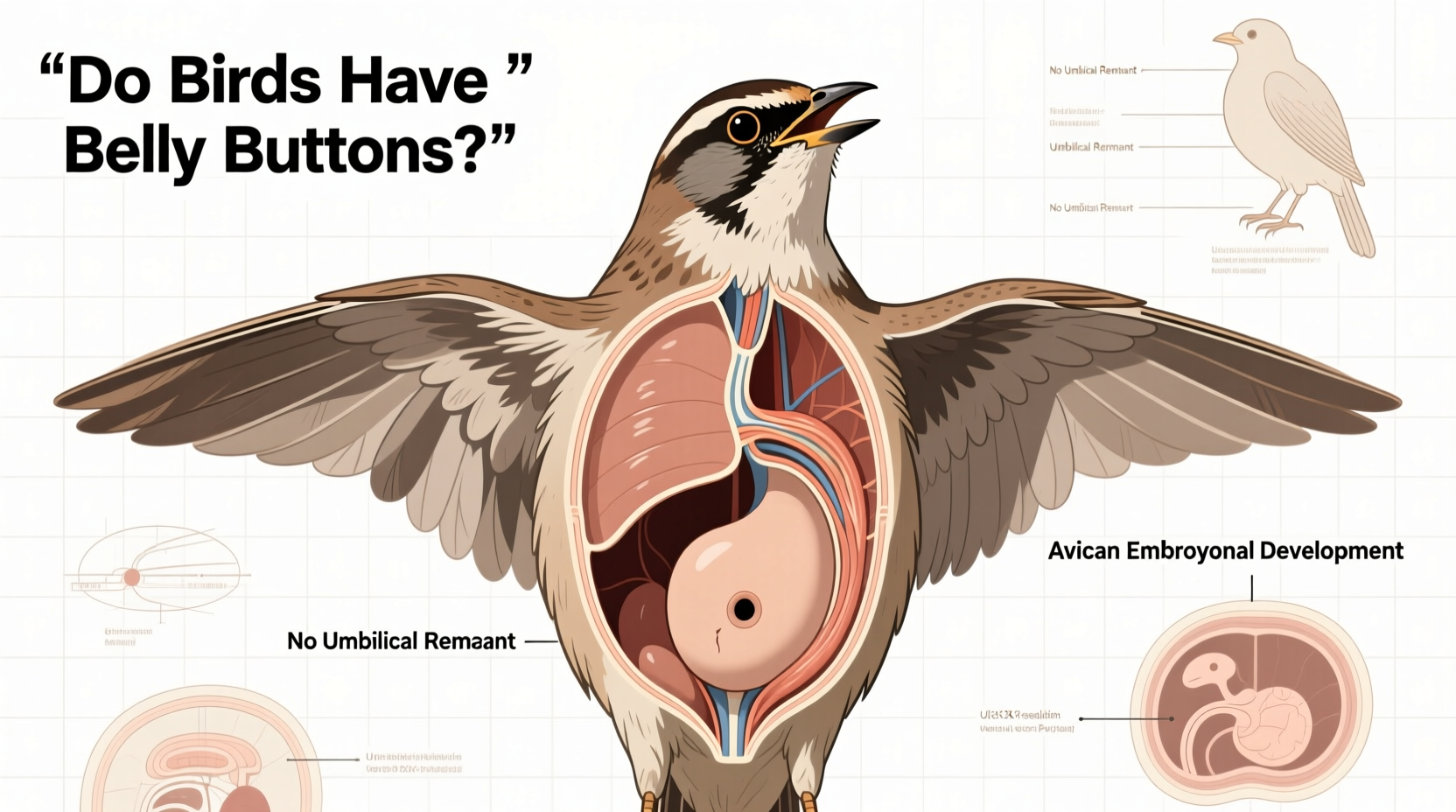

To fully understand why birds lack belly buttons, it’s essential to explore how bird embryos develop inside their eggs. Unlike mammals, which nourish their young through an umbilical cord connected to a placenta, birds rely on a self-contained life-support system within the eggshell.

Inside each bird egg are several key membranes: the amnion, allantois, yolk sac, and chorion. These structures perform functions similar to those of a mammalian placenta but without direct vascular connection to the mother. The yolk provides nutrients, while the albumen (egg white) cushions and hydrates the embryo. Oxygen enters and carbon dioxide exits through tiny pores in the shell, facilitated by the chorioallantoic membrane.

Crucially, there is no umbilical cord. Instead, blood vessels from the developing chick extend into the yolk sac and allantois to absorb nutrients and manage waste. When the chick is ready to hatch, these vessels naturally regress, and any remaining tissue is reabsorbed before hatching. Because there's no physical cord connecting the chick to its mother that needs to be severed, there's no need for a scar—the defining feature of a belly button.

Anatomical Evidence: What Happens at Hatching?

When a baby bird hatches, its abdominal wall closes seamlessly. The site where the yolk sac was once attached heals internally, leaving no external mark. In fact, newly hatched chicks often still have some residual yolk mass inside their body cavity, which continues to provide nutrition for the first few days of life. This internal absorption process is efficient and leaves no trace on the skin surface.

Some people might mistake small folds or slight discolorations near a hatchling’s abdomen as a potential “belly button,” but these are not scars from cord detachment. They are simply natural variations in feather growth patterns or temporary skin folds that disappear as the bird grows.

In contrast, human and other mammalian newborns have a visible stump after the umbilical cord is cut, which eventually dries up and falls off, leaving the navel. Since birds bypass this entire mechanism, the anatomical prerequisite for a belly button simply doesn’t exist.

Comparative Anatomy: Do Any Non-Mammals Have Belly Buttons?

Birds aren't the only animals without belly buttons—most non-placental species share this trait. Reptiles, amphibians, fish, and monotremes (like the platypus and echidna, which are egg-laying mammals) also lack traditional navels.

Even among mammals, only placental mammals (Eutherians) have true belly buttons. Marsupials like kangaroos and opossums give birth to highly underdeveloped young that complete development in a pouch. Although they have a brief umbilical connection, it typically breaks early and heals without forming a noticeable scar.

The platypus, despite being a mammal, lays eggs and thus lacks a conventional navel. This reinforces the rule: if an animal develops outside the mother’s body in an egg with no sustained umbilical link, it won’t have a belly button.

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Origins

While the scientific answer to do birds have belly buttons is rooted in embryology, the question often arises from deeper curiosity about origins and identity. Across cultures, birds symbolize freedom, transcendence, and spiritual rebirth. Their emergence from eggs has long been associated with creation myths and cycles of renewal.

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the cosmic egg represented the origin of life, from which the sun god emerged. Similarly, in Hindu cosmology, the universe is said to originate from a golden egg, or Hiranyagarbha. These symbolic associations highlight how the mystery of beginnings—akin to wondering where birds come from or if they have belly buttons—has fascinated humans for millennia.

So while birds don’t have physical navels, they carry symbolic ones in cultural narratives. Just as a belly button marks personal origin for humans, the egg serves as a universal symbol of avian genesis.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Anatomy

One widespread misconception is that all animals must have some kind of birth-related scar. This assumption stems from anthropomorphism—the tendency to project human traits onto animals. People may look at a fluffy hatchling and assume it went through a process similar to human birth, complete with cord-cutting and scarring.

Another myth is that feathers hide a bird’s belly button. However, even in featherless areas—such as the legs or around the cloaca—there is no navel-like structure. Close examination of bird anatomy, including dissections and veterinary studies, confirms the absence of such a feature.

Additionally, some confuse the uropygial gland (preen gland) near the base of the tail with a possible navel. But this gland produces oil for feather maintenance and has no connection to embryonic development.

Implications for Bird Watching and Avian Research

For bird watchers and ornithologists, understanding avian reproduction enhances appreciation of nesting behaviors and chick development. Observing nestlings grow from helpless hatchlings to fledglings can offer insights into evolutionary adaptations.

If you're observing baby birds in the wild, keep in mind that their rapid growth is fueled by either stored yolk reserves (in altricial species) or frequent feeding by parents. Knowing that they developed entirely within an egg helps explain their vulnerability during early stages and underscores the importance of undisturbed nesting environments.

Researchers studying avian embryology use advanced imaging techniques to observe blood vessel networks in eggs. These studies confirm that nutrient transfer occurs via diffusion and vascularization across membranes—not through a centralized cord. This knowledge supports conservation efforts, captive breeding programs, and poultry science.

How to Observe Bird Development Safely and Ethically

If you’re interested in witnessing bird development firsthand, consider the following ethical guidelines:

- Avoid disturbing active nests: Many bird species are protected by law. Tampering with nests, eggs, or chicks can result in fines and harm to wildlife.

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Maintain a safe distance to prevent stress or abandonment.

- Support educational farms or nature centers: Some facilities allow observation of chicken or waterfowl hatching under controlled conditions.

- Participate in citizen science projects: Programs like NestWatch encourage responsible monitoring and data collection.

By respecting natural processes, enthusiasts can deepen their understanding of avian life cycles without interfering.

Regional and Species Variations in Egg Development

While all birds share the same basic method of development—inside calcified eggs—there are fascinating variations across species and regions. For example:

| Species | Egg Incubation Period | Yolk Absorption Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| House Sparrow | 10–14 days | 1–2 days post-hatch | Altricial; born blind and naked |

| Chicken | 21 days | 3–5 days post-hatch | Residual yolk supports early growth |

| Barn Owl | 29–34 days | 2–3 days post-hatch | Develops down feathers quickly |

| Emu | 56 days | Up to 7 days post-hatch | High yolk content for desert survival |

These differences reflect adaptations to environment, predation pressure, and parental care strategies. Yet despite these variations, none involve a belly button formation.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do any birds have something similar to a belly button?

- No known bird species has a structure equivalent to a mammalian belly button. The yolk sac attachment site heals internally with no external scar.

- Can you see a scar on a newly hatched bird?

- No. Any remnants of internal connections are fully reabsorbed before or shortly after hatching. There is no external wound or scab.

- Why do people think birds might have belly buttons?

- Because humans and many pets have navels, people often assume all animals do. This reflects a common cognitive bias to generalize human biology to other species.

- Do baby birds have umbilical cords?

- No. Birds do not have umbilical cords. Nutrients are transferred via blood vessels extending into the yolk sac and allantois, not through a cord.

- Is the lack of a belly button unique to birds?

- No. Most non-placental animals—including reptiles, amphibians, and fish—also lack belly buttons. Only placental mammals develop them.

Final Thoughts: Understanding Nature on Its Own Terms

The question do birds have belly buttons may seem whimsical at first, but it opens a window into broader themes of biological diversity and human perception. By exploring avian development, we gain insight into how evolution shapes different solutions to the challenge of bringing new life into the world.

Birds’ independence from umbilical cords and placentas highlights the elegance of egg-based reproduction. Their seamless abdominal closure after hatching is not a flaw or missing feature—it’s an adaptation refined over millions of years.

Next time you watch a sparrow hop out of a nest or hear a chick peeping in a barnyard, remember: while it doesn’t have a belly button, it carries within it a story of ancient design and perfect efficiency. And perhaps, in that sense, every bird carries its own quiet mark of origin—not on its skin, but in the miracle of its existence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4