Yes, birds have exceptionally good eyesight, often far surpassing human visual capabilities in clarity, color perception, and motion detection. This advanced vision is essential for survival, enabling birds to spot prey from great distances, navigate complex environments during high-speed flight, and identify mates through subtle plumage signals. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'do birds have better eyesight than humans' reflects widespread curiosity about avian visual superiority—and the answer is a resounding yes in many key aspects.

The Biological Basis of Avian Vision

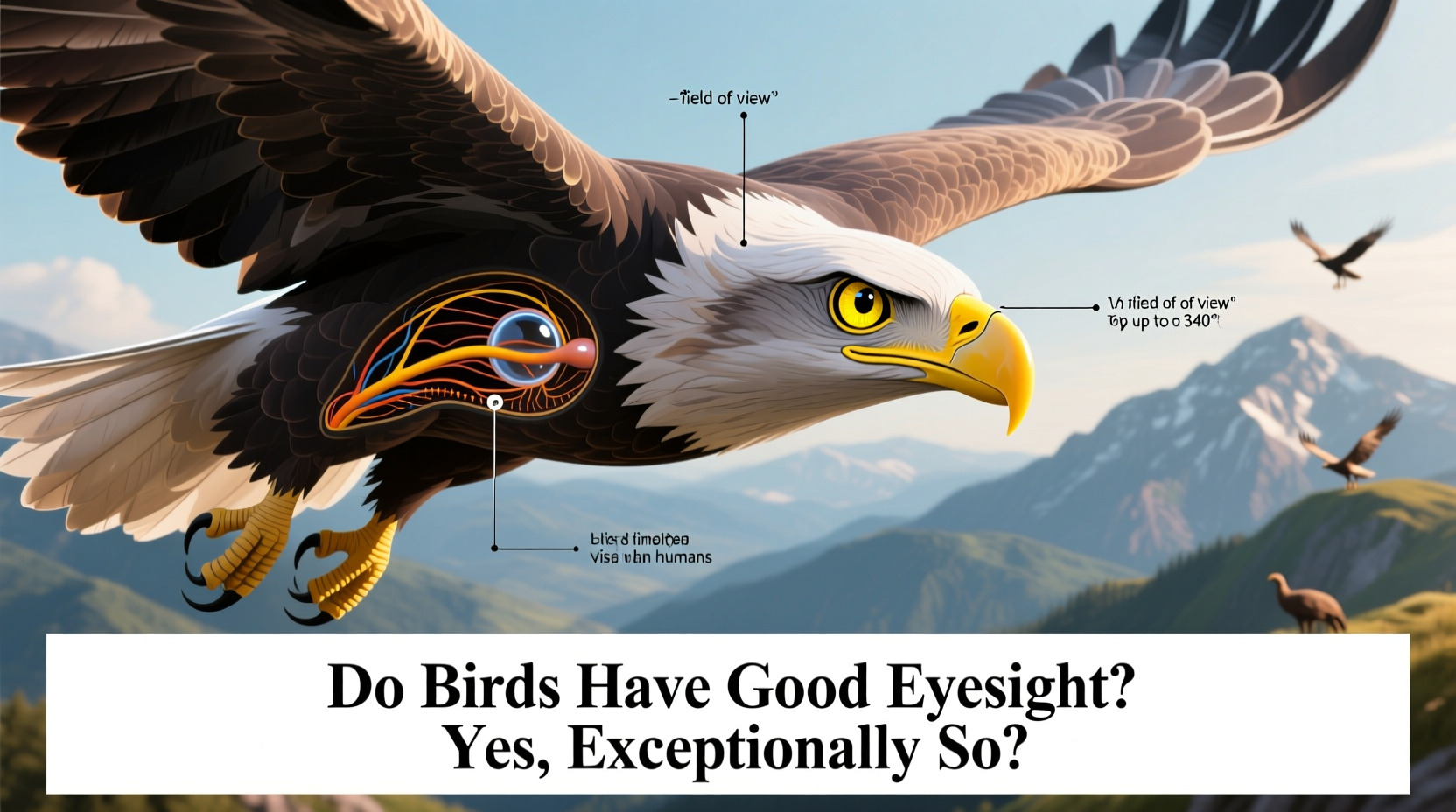

Birds possess highly evolved eyes that are proportionally larger than those of most mammals relative to their body size. These large eyes allow more light to enter, enhancing visual acuity and low-light performance. Unlike humans, whose eyes are relatively small in proportion to the skull, many birds—especially raptors like eagles and hawks—have eyes so large they can't move them within their sockets. Instead, they rely on flexible necks with up to 14 vertebrae (compared to seven in humans) to scan their surroundings.

The structure of the bird eye also contributes to superior vision. The retina contains a high density of photoreceptor cells—both rods for low-light sensitivity and cones for color vision. Many birds have two foveae (central pits in the retina with the highest concentration of cones), one for forward vision and one for lateral scanning. This dual-fovea system allows birds like the American kestrel to simultaneously focus on distant prey while monitoring their flanks for predators.

Color Perception: Seeing Beyond the Rainbow

One of the most fascinating aspects of bird eyesight is their ability to perceive ultraviolet (UV) light—a spectrum invisible to humans. Most birds are tetrachromatic, meaning they have four types of cone cells in their retinas, sensitive to red, green, blue, and ultraviolet wavelengths. This expanded color range plays a crucial role in mate selection, foraging, and navigation.

For example, many bird species use UV reflectance in their feathers to signal health and genetic fitness during courtship. What appears dull to us may be brilliantly patterned under UV light. Similarly, some fruits and berries reflect UV light, making them easier for birds to locate. Insectivorous birds may also detect UV patterns on insects or spider silk, aiding in hunting efficiency.

| Visual Feature | Birds | Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Cone Types | 4 (including UV) | 3 (red, green, blue) |

| Foveae per Eye | 1–2 | 1 |

| Field of View (average) | 300° | 180° |

| Motion Detection Sensitivity | Extremely High | Moderate |

| Visual Acuity (in raptors) | 2–8× Human Vision | 1× (baseline) |

Raptor Vision: Nature's High-Powered Binoculars

No discussion of bird eyesight would be complete without highlighting raptors—eagles, hawks, falcons, and owls. These birds exhibit some of the most acute vision in the animal kingdom. A golden eagle, for instance, can spot a rabbit from over two miles away. Its visual acuity is estimated to be 2 to 8 times greater than that of a person with 20/20 vision.

This extraordinary ability stems from several adaptations: a deep central fovea that acts like a telephoto lens, an extremely high density of cones (up to 1 million per square millimeter in some species), and a transparent third eyelid called the nictitating membrane that protects and moistens the eye without obstructing vision during flight.

Falcon eyes, particularly those of the peregrine, are adapted for high-speed dives exceeding 200 mph. They maintain sharp focus despite rapid movement thanks to specialized muscles and a rigid lens structure. Their eyes also process images faster than human eyes—detecting flickers at rates above 100 Hz compared to our 60 Hz limit—allowing them to track fast-moving prey mid-dive.

Nocturnal Vision: Owls and Low-Light Mastery

While diurnal birds excel in daylight, nocturnal species like owls have evolved for exceptional night vision. Owls have tubular-shaped eyes packed with rod cells, which are highly sensitive to dim light. Though they cannot move their eyes, their wide facial discs act like satellite dishes, funneling sound and ambient light toward the eyes and ears.

Despite common belief, owls do not see in total darkness. However, they require only one-sixth the amount of light humans need to see clearly. Their large pupils and reflective layer behind the retina—the tapetum lucidum—enhance light capture, causing their eyes to glow in the dark. This adaptation is shared with cats and other night hunters but is especially refined in species like the barn owl.

Visual Fields and Depth Perception

Birds vary widely in how their eyes are positioned, which affects both field of view and depth perception. Prey species like pigeons and ducks have eyes on the sides of their heads, giving them nearly 360-degree vision to detect predators. However, this reduces binocular overlap and depth perception.

In contrast, predatory birds have front-facing eyes with significant binocular vision—sometimes up to 70% overlap—providing precise depth judgment critical for striking prey. Humans have about 65% binocular overlap; thus, eagles and hawks outperform us in spatial accuracy when targeting moving objects.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bird Vision

Beyond biology, birds’ keen eyesight has inspired myth, metaphor, and symbolism across cultures. The eagle, revered in ancient Rome and modern America alike, symbolizes foresight, authority, and divine perspective. In Native American traditions, the eagle’s ability to soar high and see far represents spiritual insight and connection to the Creator.

Likewise, the phrase 'eagle-eyed' has entered everyday language to describe someone with sharp observation skills. This cultural recognition underscores humanity’s long-standing admiration for avian vision—not just as a biological marvel but as a metaphor for wisdom, vigilance, and clarity of purpose.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers

Understanding bird vision enhances the experience and effectiveness of birdwatching. Because birds see UV light and detect motion so well, certain practices can improve your chances of observation:

- Wear muted clothing: Bright colors and UV-reflective fabrics (common in laundry detergents) may alert birds from afar.

- Avoid sudden movements: Birds detect motion faster than humans; slow, deliberate actions reduce detection.

- Use optics wisely: High-quality binoculars with UV filtering can simulate aspects of avian vision and reveal plumage details invisible to the naked eye.

- Visit during optimal lighting: Early morning and late afternoon provide softer light, reducing glare and improving contrast for both birds and observers.

Additionally, placing feeders near natural cover gives birds a sense of safety, as their wide visual fields allow them to monitor threats while feeding. Understanding these behaviors leads to more ethical and rewarding birdwatching experiences.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Eyesight

Several myths persist about bird vision. One is that all birds see exactly like humans but sharper. In reality, their entire visual processing system differs—not just in resolution but in color range, flicker detection, and neural interpretation.

Another misconception is that birds cannot see glass. While it's true they don’t perceive transparent barriers well, this isn’t due to poor eyesight. Rather, they lack experience with artificial surfaces. Solutions like UV-reflective window decals—visible to birds but not humans—can prevent collisions by leveraging their enhanced color vision.

Regional and Species Variability

It's important to note that not all birds have equally powerful vision. Small songbirds like sparrows have good but not extraordinary eyesight compared to raptors. Seabirds like albatrosses have adaptations for spotting fish from high altitudes but may sacrifice some color discrimination for contrast sensitivity over open water.

Geographic location also influences visual demands. Tropical forest birds often rely more on vocalizations due to dense foliage, whereas open-habitat species depend heavily on long-distance sight. Urban birds may adapt to artificial lighting and reflective surfaces differently than rural populations—a growing area of research.

How to Support Bird Vision in Your Environment

You can help protect birds by minimizing hazards related to their visual strengths and limitations:

- Apply UV-patterned films to windows to reduce collisions.

- Avoid using pesticides that reduce insect populations, affecting food sources visible via UV cues.

- Install motion-sensor lights instead of constant illumination to prevent disorientation in nocturnal species.

- Participate in citizen science projects like eBird to contribute data on bird behavior and distribution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do birds see better than humans?

Yes, most birds see better than humans in terms of visual acuity, color range, and motion detection. Raptors, in particular, have significantly sharper vision.

Can birds see colors we can’t?

Yes, birds can see ultraviolet light, which is invisible to humans. This allows them to detect patterns on feathers, fruits, and flowers that we cannot perceive.

Why don’t birds collide with things if they have such good eyesight?

They usually don’t—but they frequently collide with glass because it reflects sky or vegetation, creating a false visual pathway. Their eyesight is excellent, but they don’t recognize artificial materials.

Are there birds with poor eyesight?

Some birds, like kiwis, have relatively poor eyesight and rely more on smell and touch. However, this is the exception rather than the rule.

How fast do birds process visual information?

Birds process visual stimuli faster than humans—some up to 100 times per second (Hz), compared to our maximum of around 60 Hz. This helps them track rapid movement during flight and hunting.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4