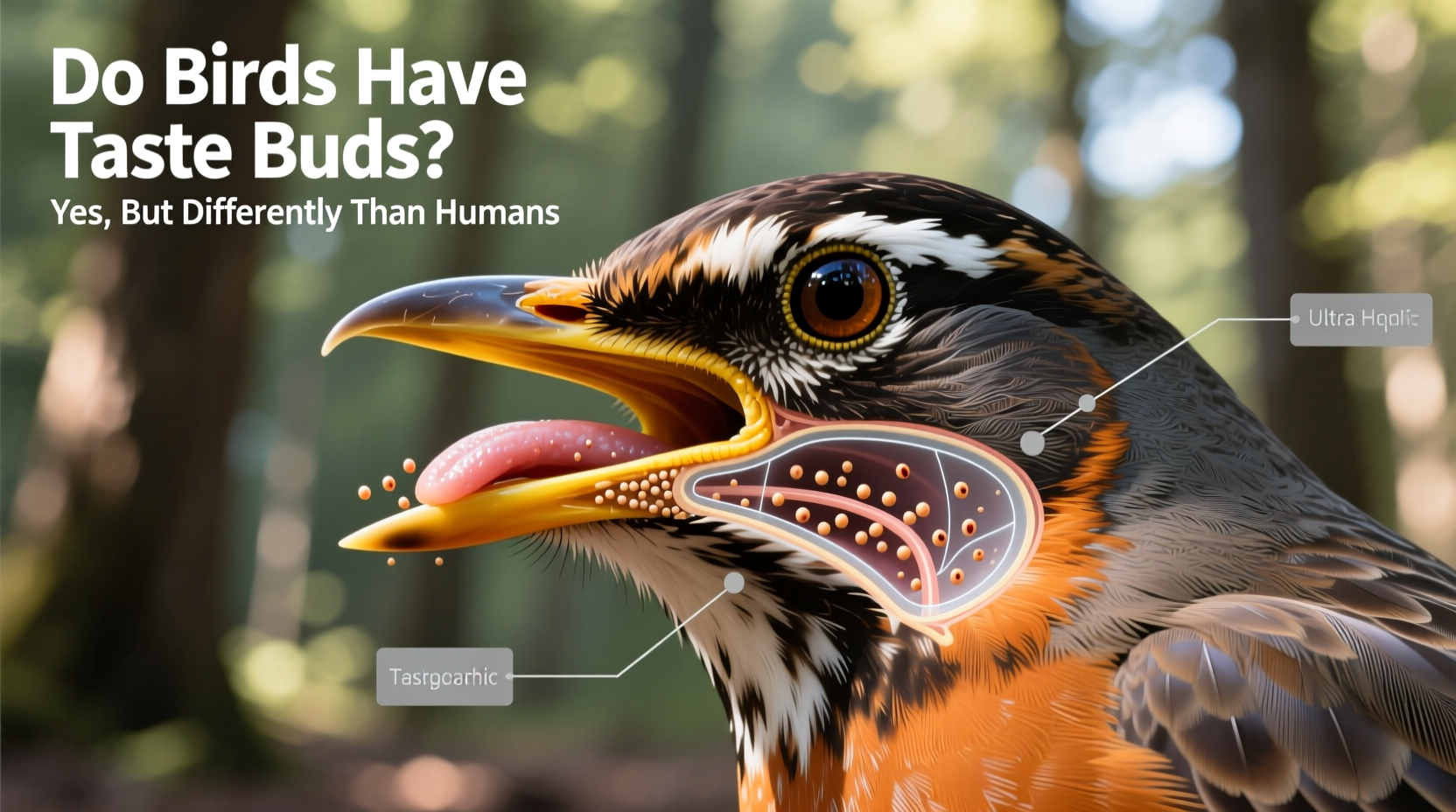

Yes, birds do have taste buds, though their sense of taste is markedly different from that of mammals. Contrary to the long-standing misconception that birds are tasteless creatures, scientific research confirms that do birds have taste buds—they absolutely do, but in far fewer numbers and with a unique anatomical arrangement compared to humans. Most birds possess between 24 and 500 taste buds, depending on the species, which is significantly less than the average human’s 8,000 to 10,000. These taste receptors are not located on the tongue in the same way as in mammals; instead, they are primarily found at the back of the oral cavity, on the roof of the mouth, and in the throat. This structural difference influences how birds detect flavors such as bitter, sour, salty, sweet, and umami, albeit with varying sensitivity across species.

The Biology of Avian Taste Perception

Birds evolved from reptilian ancestors, and their sensory systems reflect adaptations to ecological niches rather than direct parallels to mammalian biology. While early studies assumed birds had little to no sense of taste due to the lack of obvious taste papillae on their tongues, modern histological and genetic analyses have revealed functional taste buds in nearly all avian species examined. The number and distribution of these taste buds vary widely. For example, chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) have around 24 to 36 taste buds, while ducks and geese—waterfowl that often forage in murky environments—can have up to 400. This suggests an evolutionary advantage in detecting chemical cues in food when visual identification is limited.

Genetic studies have also identified taste receptor genes in birds. They possess receptors for bitter, sour, salty, and umami tastes, but interestingly, most bird species lack the T1R2 gene responsible for sweet taste perception. This absence explains why many birds show little interest in sugary substances. However, hummingbirds—an exception among birds—are known to consume nectar rich in sucrose. Research published in Science in 2014 revealed that hummingbirds repurposed their umami receptor (T1R1-T1R3) to detect sweetness, a remarkable example of molecular evolution enabling dietary specialization.

How Bird Taste Buds Influence Feeding Behavior

Understanding whether do birds have taste buds isn’t just academic—it has practical implications for bird feeding, conservation, and poultry farming. Wild birds rely heavily on vision and smell when selecting food, but taste plays a critical role in rejecting harmful or toxic items. For instance, birds can detect bitter compounds associated with plant alkaloids, which often signal toxicity. This ability helps them avoid ingesting poisonous berries or insects laced with defensive chemicals.

In backyard bird feeding, this knowledge informs best practices. Offering fresh, uncontaminated food is essential because spoiled seeds or moldy suet may produce off-flavors birds can detect. Species like finches and sparrows may abandon feeders if the seed becomes rancid, not due to spoilage visible to humans, but because of subtle taste changes only perceptible through their sensitive chemoreception.

Poultry farmers also benefit from understanding avian taste. Chickens avoid bitter-tasting feeds, so masking unpleasant flavors in medicated rations improves compliance. Conversely, enhancing palatability through sodium or amino acid additives can increase feed intake and growth rates. Studies show that broiler chickens prefer slightly salty water over plain, indicating functional salt taste receptors.

Species-Specific Variations in Taste Sensitivity

Not all birds experience taste the same way. The variation in taste bud count and receptor expression reflects dietary specialization:

- Raptors (e.g., eagles, hawks): Have relatively few taste buds, relying more on keen eyesight and instinct than flavor when consuming prey. Their taste system likely serves mainly to reject spoiled meat.

- Granivores (seed-eaters like sparrows and pigeons): Show moderate taste sensitivity, particularly to bitterness, helping them avoid toxic seeds.

- Nectarivores (hummingbirds, lorikeets): Possess adapted taste mechanisms for sugar detection despite lacking traditional sweet receptors.

- Waterfowl (ducks, swans): High taste bud counts correlate with foraging in low-visibility aquatic environments where chemical sensing compensates for reduced sight.

- Scavengers (vultures): Can tolerate strong odors and potentially foul-tasting carrion, suggesting either high tolerance or reduced sensitivity to certain aversive tastes.

| Bird Group | Average Taste Bud Count | Primary Taste Sensitivities | Dietary Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chickens | 24–36 | Bitter, salty, umami | Avoids bitter feeds; prefers sodium-enriched water |

| Ducks | ~400 | Broad spectrum | Forages underwater using chemical cues |

| Hummingbirds | ~50 | Sweet (via modified umami receptor) | Specialized nectar feeding |

| Hawks | ~50 | Limited; mainly detects spoilage | Carnivorous diet with minimal taste reliance |

| Pigeons | ~37 | Bitter, salty | Selects against toxic seeds |

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Taste

Beyond biology, the question of whether do birds have taste buds intersects with cultural narratives about avian intelligence and sensory experience. In many mythologies, birds are seen as messengers between realms, valued for their flight and song—but rarely for gustatory discernment. Yet indigenous knowledge systems often recognize birds’ refined food selection behaviors. For example, some Native American traditions observe jays avoiding certain acorns, attributing wisdom to their choices—an intuitive understanding of detoxification and taste-based avoidance now validated by science.

In literature and art, birds are seldom depicted engaging with flavor. However, contemporary environmental education increasingly emphasizes the complexity of avian senses, challenging anthropocentric views that equate intelligence with human-like perception. Recognizing that birds experience the world through different sensory priorities enriches our appreciation of their ecological roles.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Taste

Several myths persist about avian taste capabilities:

- Myth: Birds can’t taste anything because they don’t chew. Reality: Chewing is not required for taste. Taste buds respond to dissolved chemicals regardless of mastication.

- Myth: All birds love bread. Reality: Bread offers little nutritional value and may be consumed out of hunger, not preference. Many birds likely find it bland or unsatisfying.

- Myth: If a bird eats something, it must taste good. Reality: Survival drives override taste preferences. Starving birds may consume suboptimal or mildly aversive foods.

- Myth: Birds taste with their feet or feathers. Reality: No evidence supports extra-oral taste in birds. Chemoreception is confined to the oropharyngeal region.

Practical Tips for Observing and Supporting Healthy Bird Feeding Habits

If you're a birder or nature enthusiast wondering do birds have taste buds, here are actionable insights:

- Provide fresh food: Replace seed every 3–5 days to prevent mold and rancidity, both detectable via taste.

- Avoid artificial sweeteners: While birds may not taste sweetness like humans, some sugar substitutes could have unknown physiological effects.

- Offer variety: Different species prefer distinct textures and compositions. Mealworms appeal to insectivores; nyjer seed attracts finches.

- Use clean feeders: Residue buildup alters taste and promotes disease. Clean feeders weekly with mild bleach solution (1:9 bleach-to-water ratio).

- Observe behavior: If birds peck at food then discard it, they may dislike the taste or detect spoilage invisible to you.

Future Research and Technological Applications

Ongoing research into avian taste receptors holds promise for agriculture and conservation. Scientists are exploring ways to design bird-safe pesticides by exploiting bitter taste aversion—coating non-toxic repellents on crops to deter pest species without harming beneficial ones. Similarly, understanding taste-driven foraging can improve habitat restoration efforts by planting preferred native species that birds readily accept based on flavor profiles.

Advances in genomics allow researchers to map taste receptor expression across hundreds of bird species, potentially revealing evolutionary patterns linked to diet shifts. Projects like the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) initiative may soon uncover how taste genetics influence speciation and adaptation.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds taste spicy food?

- No, birds lack the TRPV1 receptor that makes capsaicin in chili peppers feel “hot” to mammals. This is why many birdseed blends include hot pepper to deter squirrels without affecting birds.

- Why do birds eat things that look gross or rotten?

- Some birds, especially scavengers like vultures, have highly acidic digestive systems capable of neutralizing pathogens. While they may detect off-flavors, their tolerance for spoilage exceeds that of humans.

- Do baby birds have taste buds?

- Yes, nestlings possess functional taste buds early in development, allowing them to reject unsuitable food brought by parents.

- Can birds distinguish between types of fat or oil in suet?

- Evidence suggests birds prefer rendered animal fats over vegetable oils, possibly due to flavor or energy density differences detectable through taste or post-ingestive feedback.

- Is there a difference in taste perception between wild and domesticated birds?

- Domestication may reduce selective pressure on taste sensitivity, but chickens and pigeons still exhibit strong aversions to bitter compounds, indicating preserved functionality.

In conclusion, the answer to do birds have taste buds is definitively yes—though their gustatory system operates under different principles than our own. From the hummingbird’s evolved sugar detection to the chicken’s rejection of bitter feed, taste plays a vital yet underappreciated role in avian life. By recognizing the sophistication of bird senses, we enhance our ability to coexist with, conserve, and appreciate these remarkable creatures.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4