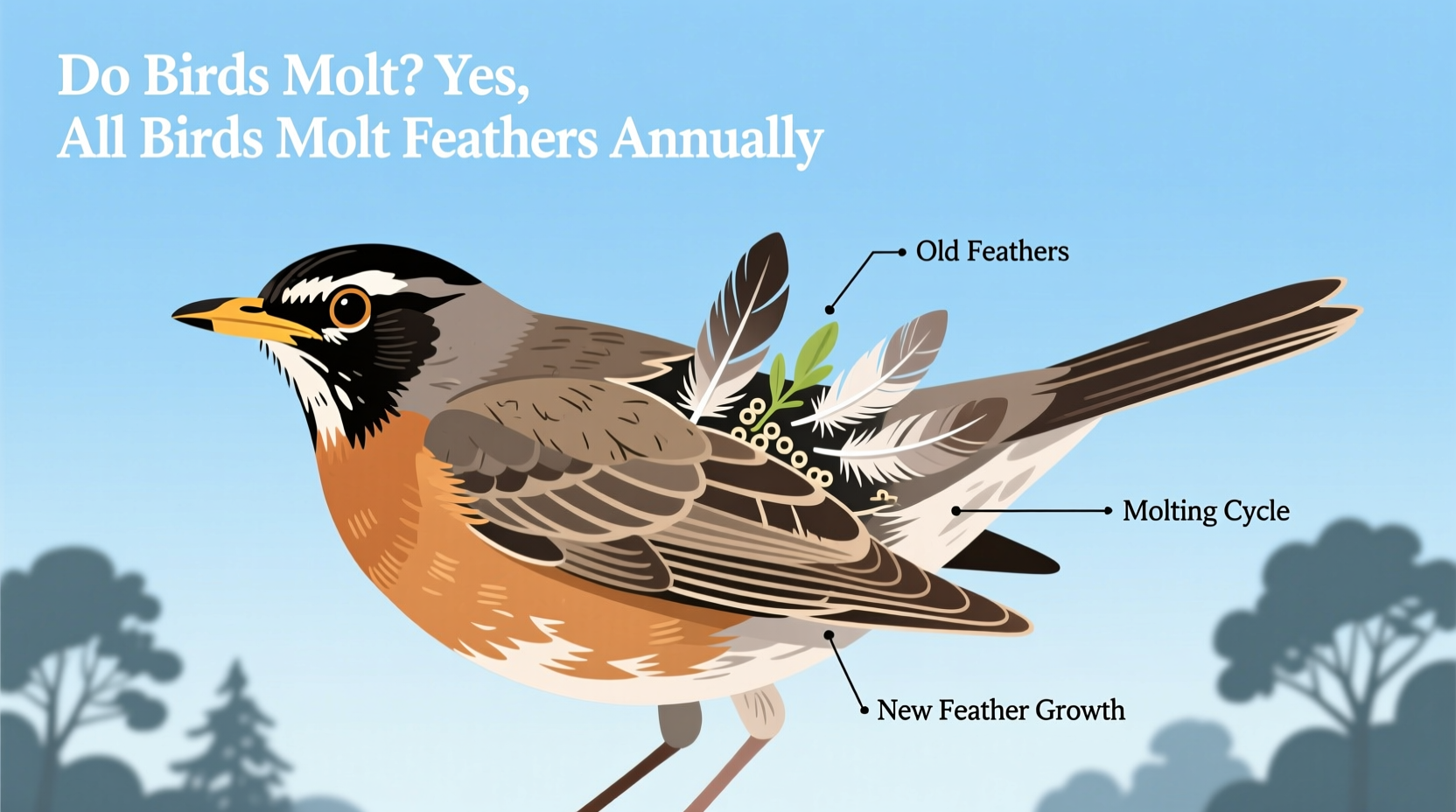

Yes, birds molt. In fact, all bird species undergo molting, the natural process of shedding old, worn feathers and growing new ones. This annual or semi-annual renewal is essential for flight, insulation, camouflage, and mating displays. A common longtail keyword variation like 'do wild birds lose feathers seasonally' reflects widespread curiosity about this biological phenomenon—and the answer is a definitive yes. Molting ensures birds maintain optimal feather condition, which directly impacts survival. Whether you're a backyard observer or a dedicated birder, understanding molting helps explain seasonal changes in plumage, behavior, and even birdwatching patterns.

What Is Molting and Why Do Birds Need It?

Molting refers to the controlled loss and regrowth of feathers in birds. Unlike mammals that continuously shed hair, birds replace their feathers in organized cycles. Feathers, though strong, degrade over time due to sun exposure, physical wear, parasites, and environmental stress. Since feathers are made of keratin—a dead protein structure—they cannot repair themselves. Therefore, periodic replacement through molting is crucial.

The primary purposes of molting include:

- Flight efficiency: Damaged or asymmetrical feathers impair aerodynamics.

- Thermal regulation: Worn down contour and down feathers reduce insulation.

- Camouflage and signaling: Bright breeding plumage often emerges after a pre-breeding molt.

- Disease prevention: Shedding feathers can help remove lice and mites.

Molting is energetically expensive. Growing new feathers demands significant protein and metabolic resources. As a result, most birds avoid overlapping molting with other high-energy activities like migration or breeding.

When Do Birds Molt? Timing Across Species and Regions

Birds typically molt once or twice per year, depending on species, climate, and life cycle. The most common pattern is a complete post-breeding (or post-nuptial) molt in late summer or early fall. For example, many North American songbirds such as warblers, sparrows, and finches begin molting in July and finish by September.

Some species exhibit two molts annually:

- A partial pre-breeding molt in late winter or spring, often involving brighter body feathers but not flight feathers.

- A complete post-breeding molt after nesting ends.

Ducks, gulls, and some seabirds undergo a rapid, simultaneous wing molt, rendering them flightless for a short period. This usually occurs right after breeding when food is still abundant and predation risk may be lower.

Geographic location also influences timing. Tropical birds may have less synchronized molting due to stable climates and extended breeding seasons. In contrast, temperate-zone birds show tightly timed molts aligned with seasonal resource availability.

How Does the Molting Process Work Biologically?

Feather growth begins in follicles embedded in the skin. During molting, old feathers loosen and fall out as new pin feathers emerge. These developing feathers are encased in a waxy sheath and supplied with blood via a vascular core. As they mature, the blood supply recedes, the sheath flakes off, and the feather unfurls into its functional form.

Molting follows specific sequences to preserve flight capability. Most passerines molt flight feathers (primaries and secondaries) in a gradual, symmetrical pattern from inner to outer wing. Tail feathers are often replaced from the center outward.

The process is hormonally regulated. Decreasing day length after summer solstice triggers hormonal shifts that initiate molt in many species. Thyroid and prolactin hormones play key roles in coordinating feather regeneration.

| Bird Group | Molt Frequency | Flightless Period? | Typical Molt Season |

|---|---|---|---|

| Songbirds (e.g., robins, sparrows) | Once yearly (complete) | No | July–September |

| Dabbling Ducks (e.g., mallards) | Twice yearly | Yes (after breeding) | Summer & Winter |

| Raptors (e.g., hawks) | Once yearly | No | Spring–Fall (gradual) |

| Hummingbirds | Once yearly | No | Late summer |

| Seabirds (e.g., albatrosses) | Irregular/slow | No | Varies by species |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Molting in Human Societies

Beyond biology, molting holds symbolic significance across cultures. Many indigenous traditions interpret feather shedding as a metaphor for personal transformation, renewal, and spiritual rebirth. In Native American symbolism, seeing molted feathers is often considered a sign of change or divine message.

In literature and art, molting represents letting go of the old to embrace growth—similar to snakes shedding skin. The phrase "a bird in molt" has historically described someone appearing disheveled or undergoing internal transition.

In modern mindfulness practices, molting is used as an analogy for emotional or psychological renewal. Just as birds invest energy into regrowing feathers during quiet periods, humans are encouraged to rest and rebuild before entering new phases of life.

How Molting Affects Birdwatching: Identification Challenges and Tips

For birders, molting poses both challenges and opportunities. A bird in transition may display a patchy appearance, making field identification difficult. For instance, a male American Goldfinch molting into non-breeding plumage loses its bright yellow feathers gradually, appearing dull greenish-brown with irregular patches.

Here are practical tips for identifying molting birds:

- Look at wing and tail feathers: These are often retained longer and show more consistent patterns.

- Note symmetry: Natural molt is symmetrical; asymmetry may indicate injury or disease.

- Check behavior: Molting birds may appear lethargic and spend more time hidden, conserving energy.

- Use seasonal context: Knowing typical molt windows helps narrow possibilities.

Birders should also understand that molt limits affect age determination. Juveniles often have a distinct preformative molt, different from adults. Field guides increasingly include molt charts to aid accurate aging and sexing.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Molting

Several myths persist about molting. One widespread belief is that finding a pile of feathers means a predator attacked a bird. While predation does leave feather clusters, healthy molting birds also naturally shed multiple feathers at once, especially during heavy body feather replacement.

Another misconception is that bald cardinals or blue jays are diseased. In reality, some individuals experience synchronous head feather loss during late summer molt, resulting in temporary baldness. New feathers regrow within 1–2 weeks.

People often confuse molting with feather plucking due to stress or illness. True pathological plucking is usually asymmetrical, accompanied by skin damage, and occurs outside normal molt seasons.

Supporting Birds During Molting: Practical Care Tips

If you maintain a backyard habitat, supporting birds during molt can improve their health and survival. Because feather production requires extra protein, offering high-protein foods is beneficial:

- Unsalted peanuts

- Mealworms (live or dried)

- Suet cakes with insect content

- Crushed eggshells (for calcium)

Ensure clean water is available for preening and hydration. Avoid using pesticides, as insects are a vital natural protein source during this period.

Limit disturbances near nesting and cover areas where birds may hide while molting. Patience is key—molting birds may visit feeders less frequently as they conserve energy.

Regional Variations and Climate Change Impacts on Molting

Molting schedules vary regionally. In southern U.S. states, molting may start earlier due to warmer springs and earlier breeding. Alaskan birds, by contrast, have compressed timelines, completing breeding and molt within a narrow window.

Emerging research suggests climate change is altering molt patterns. Warmer temperatures and shifting food availability may cause mismatches between molt timing and optimal conditions. For example, if insects peak earlier due to warming, but birds delay molt based on photoperiod cues, nutritional stress could increase.

Birders can contribute data by noting unusual plumage conditions or out-of-season molting through citizen science platforms like eBird or Project FeederWatch.

How to Verify Molting Information for Your Area

Because molt timing varies by species and location, it’s wise to consult regional resources:

- Local Audubon chapters often publish seasonal bird activity calendars.

- University extension programs provide phenology reports.

- eBird’s bar charts show expected presence and plumage codes by month.

- Specialized guides like Birding by Ear or Helm Identification Guides detail molt-related vocal and visual changes.

Always cross-reference observations with trusted sources. When uncertain, photograph the bird and consult online forums like iNaturalist or the ABA Birders’ Exchange.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bird Molting

- Do all birds molt at the same time?

- No. Molt timing depends on species, geography, and individual condition. Most temperate birds molt after breeding, but tropical species may molt asynchronously throughout the year.

- Can molting birds fly?

- Most can. Songbirds and raptors retain flight during gradual molt. However, waterfowl like ducks become temporarily flightless during their simultaneous wing feather replacement.

- How long does molting last?

- Duration varies: small songbirds take 6–8 weeks; larger birds like eagles may molt over several months. Some seabirds spread molt over multiple years.

- Is it normal to see bald birds?

- Yes. Some cardinals, blue jays, and grackles lose all head feathers simultaneously in late summer. New feathers grow back quickly and completely.

- Should I worry if I find many feathers under a tree?

- Not necessarily. Healthy birds regularly drop feathers during molt. Only concern arises if you observe injured birds, blood, or signs of distress nearby.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4