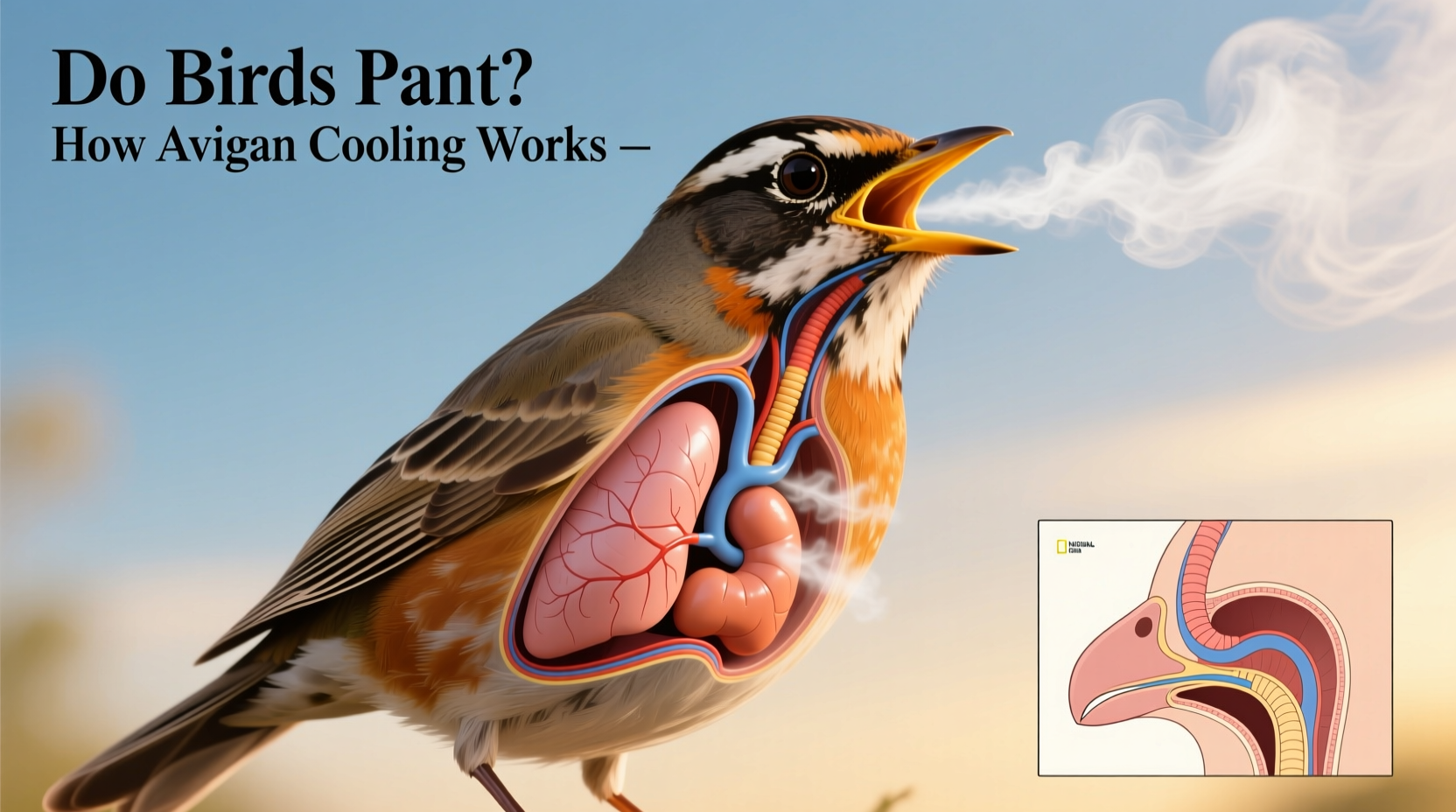

Yes, birds do pantâthough not in the same way mammals do. Bird panting is a vital thermoregulatory behavior used primarily to cool down when temperatures rise. Unlike dogs or humans, who rely heavily on evaporative cooling through rapid breathing, birds have a highly efficient respiratory system that limits traditional panting. Instead, they use a process often referred to as gular fluttering or rapid beak-opening behaviors to dissipate heat. This adaptation answers the frequently searched query: do birds pant to cool down, and reveals how avian physiology differs dramatically from mammalian counterparts.

The Biology Behind Bird Panting: More Than Just Breathing Fast

Birds lack sweat glands, which means they cannot cool themselves through perspiration like humans. Instead, they depend on respiratory evaporation and behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature. When ambient temperatures climb above their thermal neutral zone (typically between 77°F and 104°F, depending on species), birds begin exhibiting signs of heat stress mitigationâincluding what many observers describe as âpanting.â

This bird panting mechanism involves rapid opening and closing of the beak, sometimes accompanied by slight throat vibrations known as gular flutteringâespecially common in pigeons, doves, and herons. Gular fluttering increases airflow across moist surfaces in the mouth and upper respiratory tract, enhancing evaporative cooling without disrupting normal respiration patterns required for flight metabolism.

Itâs important to clarify a common misconception: while dog panting involves heavy abdominal movement and open-mouthed exhalation, birds maintain a much subtler technique. Their rigid ribcage and air-sac-based respiratory system make deep, labored breaths inefficient and potentially dangerous. Therefore, true âpantingâ in birds isnât about increasing oxygen intakeâit's strictly about releasing excess heat.

How Bird Respiration Differs From Mammals

To fully understand whether birds pant, one must first grasp how their respiratory system works. Birds possess one of the most efficient respiratory systems in the animal kingdomâa unidirectional airflow design supported by nine interconnected air sacs. Air moves continuously through rigid lungs during both inhalation and exhalation, allowing for maximal oxygen extraction even at high altitudes.

This efficiency comes at a cost: limited flexibility in breathing rate modulation. While mammals can rapidly increase respiratory rates during exertion or heat exposure, birds face physiological constraints due to their need for precise ventilation-to-perfusion matching. Excessive hyperventilation could lead to respiratory alkalosisâan imbalance caused by blowing off too much carbon dioxideâwhich makes uncontrolled panting risky.

Instead of widespread panting across all species, birds evolved targeted cooling strategies:

- Gular fluttering: Rapid vibration of the thin skin in the throat area (e.g., mourning doves)

- Wing drooping: Holding wings slightly away from the body to expose featherless areas (axillae)

- Perching in shade: Behavioral avoidance of direct sunlight

- Urohidrosis: Some birds, like vultures, defecate on their legs to cool via evaporation

Species That Exhibit Bird Panting Behaviors

Not all birds pant equallyâor visibly. The likelihood of observing panting depends on species, habitat, and environmental conditions. Below is a table highlighting key examples:

| Bird Species | Cooling Method | When Observed | Habitat Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mourning Dove | Gular fluttering | Midday summer heat | Urban/suburban areas |

| Great Blue Heron | Beak gaping + neck extension | After sunbathing or fishing | Wetlands |

| Pigeon (Rock Dove) | Rapid beak opening | In cities with heat islands | High-density urban |

| Turkey Vulture | Urohidrosis + minimal panting | During soaring in hot climates | Open country |

| Canary | Subtle beak movements | In overheated cages | Indoor captivity |

These variations underscore an essential truth: do birds pant is not a yes-or-no question but a spectrum influenced by evolutionary adaptation and ecological niche.

Environmental Triggers That Cause Birds to Pant

Heat is the primary trigger for bird panting, but other factors amplify the need for cooling:

- Ambient temperature: Above 90°F (32°C), many temperate-zone birds initiate cooling behaviors.

- Solar radiation: Direct sun exposure significantly raises surface temperature, especially in dark-plumaged birds.

- Humidity: High humidity reduces evaporative efficiency, forcing longer or more intense panting sessions.

- Activity level: Post-flight recovery often includes brief panting episodes to shed metabolic heat.

- Dehydration: Lack of water impairs evaporative cooling, making panting less effective and more prolonged.

In extreme cases, such as heatwaves in urban environments, birds may exhibit distress signals beyond panting: lethargy, inability to fly, or lying prone with wings spread. These are emergency signs requiring immediate intervention if the bird is accessible and safe to assist.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Panting

While modern science explains bird panting as a biological necessity, various cultures throughout history have interpreted such behaviors symbolically. In Native American traditions, particularly among Pueblo tribes, birds displaying unusual breathing patterns were seen as messengers from spirit realms, signaling shifts in weather or spiritual unrest.

In some African folklore, doves seen fluttering their throats rapidly were believed to be whispering prayers to ancestral spirits. Though unrelated to thermoregulation, these interpretations reflect humanityâs long-standing fascination with avian behavior. Today, birdwatchers might misinterpret gular fluttering as distress rather than normal coolingâhighlighting the importance of education in reducing unnecessary human interference.

Interestingly, the phrase âdo birds pant like dogsâ appears frequently in online forums, revealing a public tendency to anthropomorphize animal behaviors. Educators and conservationists emphasize distinguishing between mammalian panting and avian adaptations to prevent misconceptions about animal welfare.

Practical Tips for Observing and Supporting Birds During Heat Stress

If you're a birder, backyard feeder host, or wildlife observer, recognizing authentic bird panting versus signs of distress is crucial. Here are actionable steps:

- Provide fresh water sources: Birdbaths with shallow edges allow drinking and foot-dipping, aiding passive cooling.

- Shade native plants: Plant trees and shrubs that offer natural shelter during peak heat hours (10 AM â 4 PM).

- Avoid handling panting birds: Unless clearly injured or grounded, panting is likely normal. Interference can cause additional stress.

- Monitor captive birds closely: Pet birds like parakeets or cockatiels showing constant open-beak breathing may be overheating or illâconsult an avian vet immediately.

- Report distressed wildlife: If a bird is listless, unable to stand, or convulsing despite panting, contact local wildlife rehabilitation centers.

Additionally, timing matters. Early morning and late evening observations are best for spotting normal activity. Midday sightings of stationary, panting birds should prompt assessment of environmental conditions before assuming illness.

Common Misconceptions About Do Birds Pant

Despite growing awareness, several myths persist:

- Myth: All birds pant loudly like dogs.

Truth: Most bird cooling is silent and subtle, involving minimal sound or movement. - Myth: Panting always indicates sickness.

Truth: Itâs a normal response to heat; context determines if itâs concerning. \li>Myth: Birds sweat through their feathers. - Myth: Only large birds pant.

Truth: Even small songbirds use modified forms of respiratory cooling in hot conditions.

Truth: They have no sweat glandsâcooling occurs only through respiration and behavior.

Understanding these nuances helps promote accurate interpretation of avian behavior in both wild and domestic settings.

Regional Variations in Bird Panting Frequency

Geographic location plays a significant role in how often bird panting is observed. In arid regions like the Southwestern United States, species such as cactus wrens and roadrunners regularly employ panting and gular fluttering during summer months. Conversely, in cooler maritime climates like the Pacific Northwest, panting is rare and usually only seen during unseasonable heatwaves.

Urban heat islands also create microclimates where bird panting occurs more frequently. City-dwelling pigeons, for example, experience surface temperatures up to 20°F higher than rural counterparts due to asphalt and concrete absorption. This increases reliance on respiratory cooling methods year-round.

Climate change is further altering these dynamics. Rising global temperatures mean that historically cool regions now see more frequent instances of bird pantingâpotentially straining species not adapted to sustained heat exposure.

FAQs: Common Questions About Whether Birds Pant

- Do birds pant when they are stressed?

- Yes, birds may pant under thermal stress or anxiety, but itâs primarily linked to heat, not emotional states like in mammals.

- Is bird panting the same as dog panting?

- No. Dog panting uses abdominal muscles and heavy exhalation; birds use gular fluttering and beak movements without deep chest involvement.

- Can panting harm birds?

- Prolonged panting can lead to dehydration or respiratory imbalances, especially in enclosed spaces like cages or during heatwaves.

- What should I do if I see a bird panting?

- Observe first. If the bird is active and in shade, itâs likely fine. Offer nearby water. Only intervene if the bird shows signs of collapse or disorientation.

- Do baby birds pant?

- Nestlings rarely pant because parents regulate nest temperature. Fledglings may begin using panting techniques once out of the nest and exposed to sun.

In conclusion, the answer to âdo birds pantâ is nuanced but clear: birds do engage in panting-like behaviors, though these differ fundamentally from mammalian panting. Through specialized mechanisms like gular fluttering and strategic posturing, birds efficiently manage body heat within the constraints of their unique respiratory anatomy. For researchers, birders, and pet owners alike, understanding this behavior enhances both scientific literacy and compassionate stewardship of avian life.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4