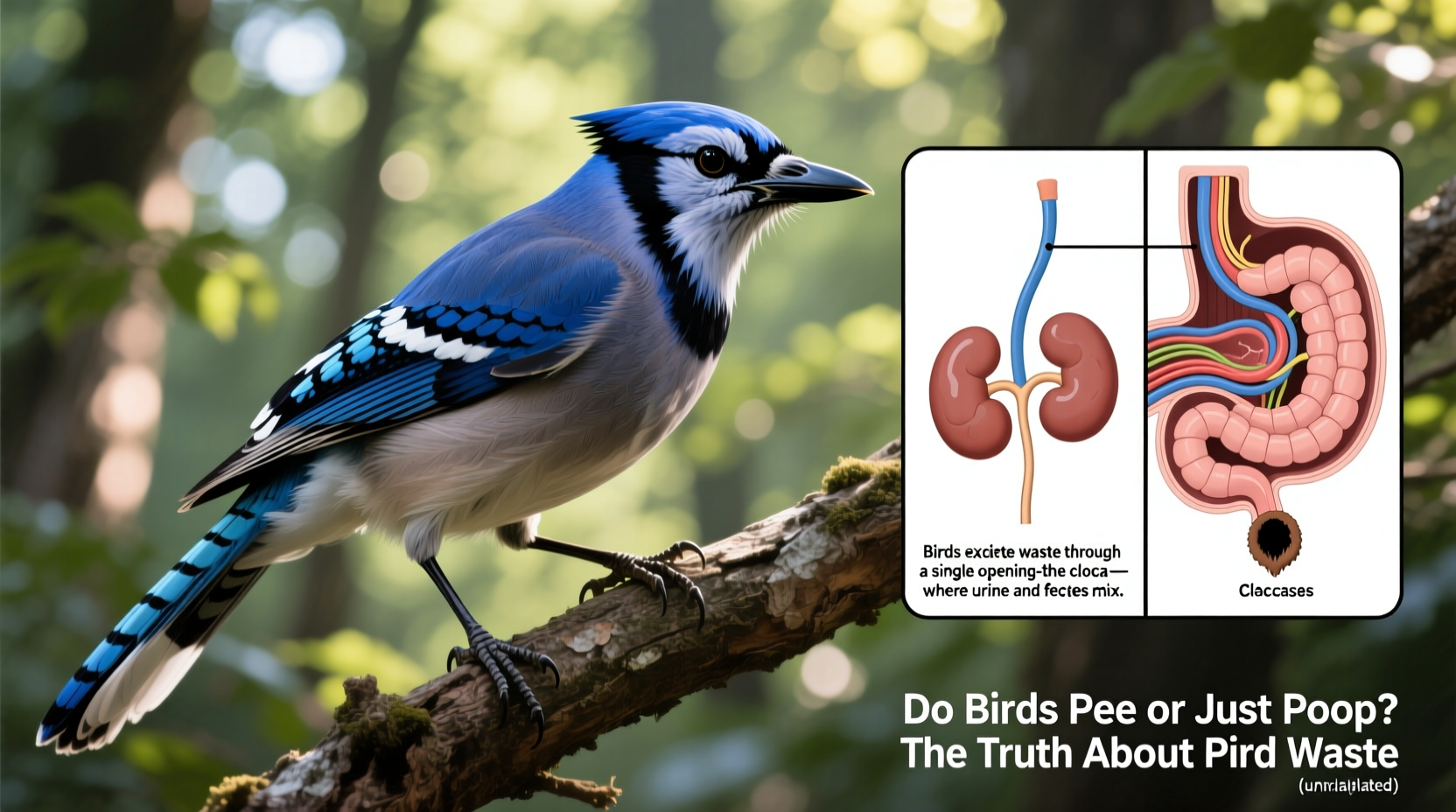

Birds do not pee like mammals; instead, they excrete waste in a combined form of urine and feces through their cloaca. This single white and dark dropping you often see on your car or sidewalk is actually both 'pee' and 'poop' together — a key adaptation that helps birds stay lightweight for flight. So, to answer the common question: do birds pee or just poop?, the biological truth is that birds don’t produce liquid urine like humans do, but they do eliminate nitrogenous waste — just in a different, more efficient way.

The Biology of Bird Excretion: How Do Birds Get Rid of Waste?

Unlike mammals, which separate liquid urine and solid feces, birds have evolved a unique excretory system optimized for energy efficiency and weight reduction. This is crucial for flight, where every gram matters. Birds lack a bladder and do not produce urea-rich liquid urine. Instead, their kidneys filter waste from the bloodstream and convert nitrogenous byproducts into uric acid.

Uric acid is a semi-solid, white paste that requires minimal water to excrete. This contrasts sharply with mammals, which expel urea dissolved in large amounts of water as urine. Because birds obtain most of their water from food and conserve it aggressively, producing uric acid instead of urea is a major survival advantage, especially in arid environments or during long migratory flights.

The process works like this: after digestion, metabolic wastes are filtered by the kidneys. Nitrogenous waste (mainly from protein breakdown) is converted into uric acid in the liver and then transported to the cloaca — a multi-purpose opening used for excretion, reproduction, and egg-laying. In the cloaca, uric acid mixes with digested solids (feces) before being expelled as a single dropping.

What Does Bird Poop Actually Consist Of?

If you’ve ever noticed the distinct appearance of bird droppings — a dark center surrounded by a white, chalky substance — you’re seeing both components of avian waste. The dark part is the actual fecal matter, composed of digested food remnants. The white portion is the crystallized uric acid, which serves the same detoxifying function as mammalian urine.

This combination means that when a bird 'poops,' it’s technically eliminating both solid and liquid waste simultaneously. There is no separate peeing process. So while it may look like birds only poop, they are, in fact, doing both — just in one compact package.

The consistency of bird droppings can vary depending on species, diet, hydration levels, and health. For example, seed-eating birds like pigeons or sparrows tend to produce drier, more crumbly droppings, while fruit-eating birds such as toucans or orioles may leave slightly wetter deposits due to higher water intake from their food.

Why Don’t Birds Have a Urethra or Bladder?

Evolution has shaped birds to prioritize lightness and efficiency. Having a bladder would add unnecessary weight and require additional muscular control, neither of which benefit flight performance. Additionally, storing liquid urine would increase water loss through evaporation and create osmotic challenges, particularly in flying species that already face dehydration risks at high altitudes.

Instead, birds rely on their highly efficient kidneys and the cloacal system to manage waste without retaining fluids. The absence of a urethra further streamlines the excretory process. All waste — whether solid, liquid, or reproductive — exits via the cloaca, making it one of the most versatile organs in the animal kingdom.

Differences Among Bird Species

While all birds share the basic mechanism of excreting uric acid along with feces, there are subtle differences across species based on lifestyle and habitat:

- Seabirds (e.g., gulls, albatrosses): Often consume salty diets and possess specialized salt glands near their eyes that excrete excess sodium. Their droppings may appear saltier or more concentrated.

- Raptors (e.g., eagles, hawks): Carnivorous diets result in darker, more compact fecal cores due to bone and tissue digestion. Pellets of indigestible material (like fur and feathers) are regurgitated separately.

- Poultry (e.g., chickens, ducks): Domesticated birds show similar excretion patterns but may have altered droppings due to commercial feed, medications, or disease.

- Migratory birds: During long flights, they reduce gut mass and excrete less frequently, sometimes holding waste until landing.

| Bird Type | Diet | Waste Characteristics | Special Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon | Seeds, grains | Dry, white-and-black droppings | Efficient water conservation |

| Bald Eagle | Fish, small animals | Large, white-splattered droppings | Regurgitates indigestible parts as pellets |

| Hummingbird | Nectar, insects | Tiny, nearly invisible droppings | High metabolism, frequent excretion |

| Emu | Plants, insects | Loose, green-tinged droppings | Ground-dwelling, less flight pressure |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Waste

Several myths persist about bird excretion, often stemming from misunderstanding their anatomy:

- Myth: Birds don’t pee because they don’t drink water.

Fact: Most birds do drink water, though many get sufficient moisture from food. They still produce metabolic waste that must be eliminated. - Myth: The white part of bird poop is feces.

Fact: The white portion is uric acid — the equivalent of urine. The dark center is the true fecal matter. - Myth: If a bird doesn’t leave puddles, it isn’t peeing.

Fact: Liquid urine isn’t necessary for waste removal. Uric acid achieves the same goal with far less water. - Myth: Baby birds pee and poop inside the nest.

Fact: Nestlings often excrete in sealed fecal sacs that parents remove to keep nests clean and avoid attracting predators.

Implications for Bird Watching and Avian Health

For bird watchers and pet bird owners alike, understanding bird waste can provide valuable insights into health and behavior. Changes in droppings — such as color, consistency, frequency, or odor — can signal illness. For instance:

- Green droppings may indicate liver disease or dietary changes.

- Excessively watery droppings could suggest infection or kidney dysfunction.

- Red or black specks might point to internal bleeding.

- Lack of urates (white part) can be a sign of dehydration or renal failure.

In wild bird observation, noting where and how often birds defecate can also reveal feeding zones, roosting sites, and territorial behaviors. For example, colonial seabirds like gulls or cormorants often defecate over water to avoid fouling nesting cliffs, while urban pigeons leave droppings wherever they perch.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Bird Droppings

Beyond biology, bird droppings carry surprising cultural significance across societies. In many cultures, being hit by bird poop is considered good luck — a belief rooted in rarity and unpredictability. After all, the odds of being targeted are low, so if it happens, it must mean fortune is smiling upon you.

In Japan, some people view bird droppings as a symbol of unexpected windfalls. In parts of Eastern Europe, farmers historically saw bird droppings on crops as a sign of fertility and natural fertilization. Conversely, in urban settings, bird waste is often seen as a nuisance, prompting cities to install deterrents like spikes or netting on buildings.

Interestingly, guano (accumulated bird droppings, especially from seabirds) has played a major role in agriculture and history. In the 19th century, islands rich in guano were heavily mined and even sparked international conflicts due to its value as a potent natural fertilizer. Peru, for example, built an entire economy around guano exports before synthetic fertilizers became widespread.

Practical Tips for Observing and Managing Bird Waste

Whether you're a birder, pet owner, or city dweller, here are actionable tips related to bird excretion:

- For bird watchers: Use droppings to locate active roosts or feeding areas. Look for accumulations under trees, power lines, or bridges.

- For pet bird owners: Monitor droppings daily. Sudden changes warrant a vet visit. Provide fresh water and a balanced diet to support kidney health.

- For homeowners: Clean bird droppings promptly using gloves and disinfectant. Uric acid is mildly corrosive and can damage paint or stone over time.

- For travelers: Wear hats in areas with large flocks (e.g., seaside towns). Many locals sell "bird umbrella" souvenirs for comic relief.

- For educators: Use bird waste as a teaching tool to explain evolutionary adaptations, nitrogen cycles, and ecosystem roles.

FAQs About Bird Excretion

- Do birds pee and poop from the same hole?

- Yes, birds excrete both urine (as uric acid) and feces through the cloaca, a single opening used for digestion, reproduction, and waste elimination.

- Why is bird poop white?

- The white part is uric acid, the bird’s version of urine. It’s a paste-like waste product that conserves water and is less toxic than urea.

- Can bird droppings make you sick?

- Yes, in rare cases. Accumulated droppings can harbor fungi like Histoplasma capsulatum, which causes respiratory illness if inhaled. Always wear protection when cleaning large accumulations.

- Do baby birds pee and poop?

- Yes, but nestlings often excrete in fecal sacs — mucous-covered packets that parents remove to keep the nest clean and reduce predation risk.

- Is bird poop good for plants?

- In moderation, yes. Guano is rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. However, excessive buildup can burn plants or introduce pathogens.

In summary, the answer to do birds pee or just poop lies in understanding their unique physiology. Birds don’t pee in the mammalian sense, but they do excrete liquid waste — transformed into a dry, white paste called uric acid — mixed with their feces. This efficient system supports their high-energy lifestyles and flight capabilities. From backyard feeders to remote oceanic islands, bird droppings tell stories of biology, ecology, and even human history. So next time you see a splatter on your windshield, remember: it’s not just mess — it’s evolution in action.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4