Birds are not mammals; they are a distinct class of vertebrate animals known as Aves. This fundamental distinction is central to understanding the question: do do bird classifications align with mammalian traits? The answer is no—birds differ from mammals in key biological ways, including reproduction, anatomy, and physiology. While both birds and mammals are warm-blooded and have highly developed brains, birds lay eggs, possess feathers, and have lightweight skeletons adapted for flight, none of which are defining characteristics of mammals. These differences place birds in their own evolutionary lineage, separate from mammals, despite some shared features due to convergent evolution. Understanding whether birds are mammals helps clarify common misconceptions and deepens appreciation for avian biology and diversity.

Biological Classification: Why Birds Are Not Mammals

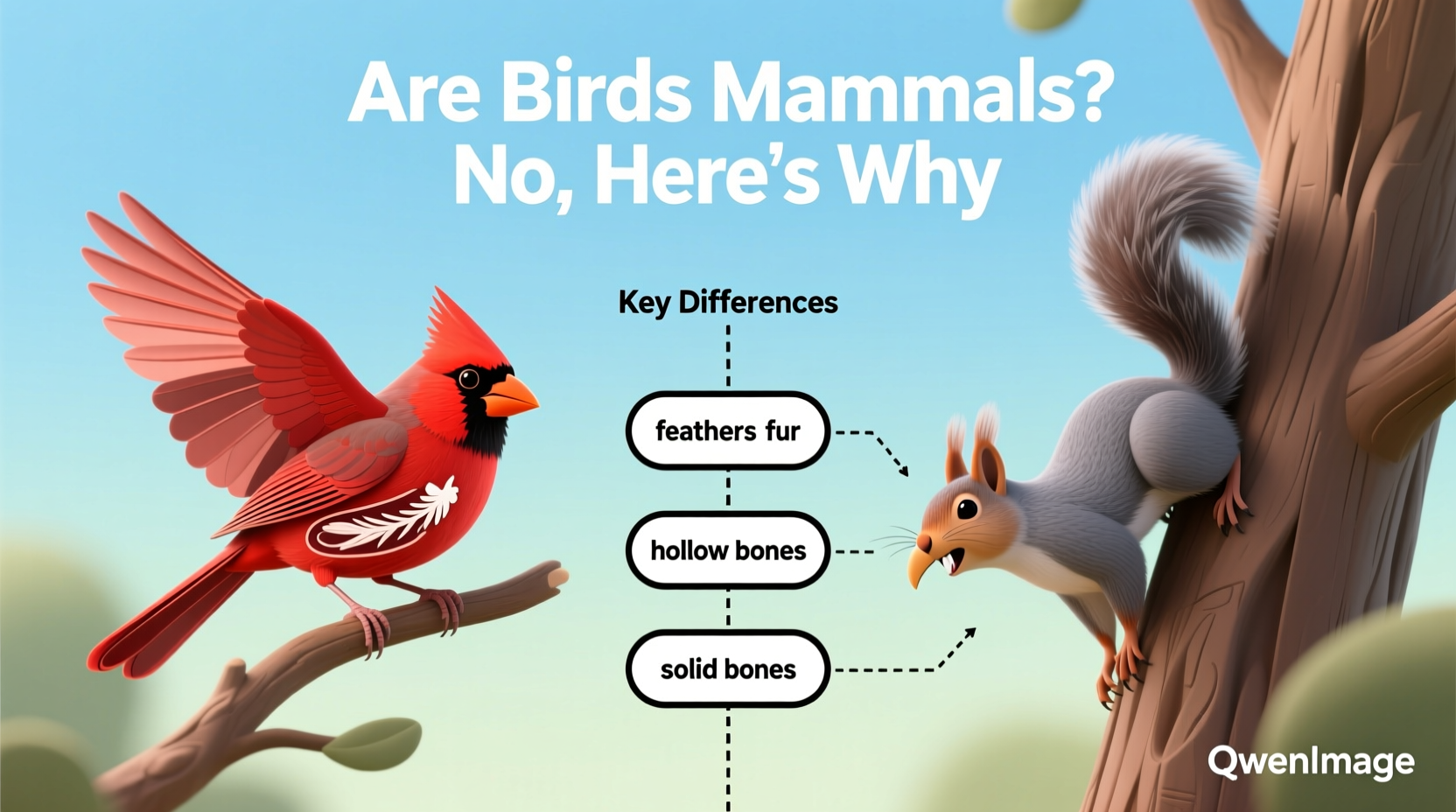

The confusion over whether birds are mammals often stems from superficial similarities, such as being warm-blooded (endothermic) and caring for their young. However, taxonomically, birds belong to the class Aves, while mammals belong to Mammalia. One of the most definitive distinctions lies in reproduction: mammals typically give birth to live young and nurse them with milk produced by mammary glands—a trait unique to mammals. In contrast, all birds reproduce by laying hard-shelled eggs and lack mammary glands entirely.

Another critical difference is integumentary structure. Birds are uniquely characterized by feathers, which serve functions in flight, insulation, and display. No other animal group possesses true feathers. Mammals, on the other hand, are defined by the presence of hair or fur at some stage of life. Additionally, birds have beaks without teeth (in modern species), whereas mammals have jaws with differentiated teeth.

Skeletal adaptations further distinguish birds. Their bones are hollow and fused in certain areas, reducing weight for flight. They also have a highly efficient respiratory system with air sacs that allow continuous airflow through the lungs—an advantage for high metabolic demands during flight. Mammals lack this one-way airflow system and generally have denser bones suited for terrestrial locomotion rather than aerial mobility.

Evolutionary Origins: Birds and Dinosaurs

One of the most fascinating aspects of avian biology is that birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Fossil evidence, especially from species like Archaeopteryx and numerous feathered dinosaurs discovered in China, supports the scientific consensus that birds evolved from small, carnivorous dinosaurs around 150 million years ago. This makes birds the only living representatives of the dinosaur lineage.

This evolutionary heritage explains many avian traits. Feathers, once thought to have evolved solely for flight, likely originated for insulation or display in non-avian dinosaurs. Over time, natural selection favored modifications that enabled gliding and eventually powered flight. Thus, when asking 'do do bird ancestors resemble reptiles more than mammals?', the answer is a resounding yes—birds share a closer common ancestor with crocodiles than with any mammal.

Physiological Differences Between Birds and Mammals

Beyond structural differences, birds exhibit unique physiological processes. For example, their metabolic rate is significantly higher than that of most mammals, supporting sustained flight and thermoregulation in diverse climates. To meet these energy demands, birds have rapid heart rates and consume large amounts of food relative to body size.

Birds also possess a four-chambered heart like mammals, allowing complete separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. However, their circulatory system operates under higher pressure to support intense aerobic activity. Moreover, birds excrete nitrogenous waste primarily as uric acid rather than urea, which reduces water loss—an adaptation crucial for flight and survival in arid environments.

Respiration in birds is another area of stark contrast. Unlike mammals, where air moves in and out of the lungs in a tidal fashion, birds have a unidirectional flow facilitated by air sacs distributed throughout their body cavity. This allows fresh oxygen to enter the lungs even during exhalation, making their respiratory system among the most efficient in the animal kingdom.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds Across Civilizations

Birds have held profound symbolic meanings across cultures and historical periods. In ancient Egypt, the Ba—depicted as a human-headed bird—represented the soul’s ability to travel between worlds after death. Similarly, in Greek mythology, doves were associated with Aphrodite, goddess of love, symbolizing peace and devotion.

In Native American traditions, eagles are revered as messengers between humans and the divine, embodying courage, wisdom, and spiritual insight. The bald eagle, now a national symbol of the United States, reflects this enduring reverence. Meanwhile, ravens feature prominently in Norse and Indigenous Pacific Northwest folklore as tricksters and creators, highlighting their intelligence and adaptability.

In Eastern philosophies, cranes symbolize longevity and good fortune in Chinese and Japanese cultures. Their graceful movements inspire martial arts forms and appear frequently in classical paintings and poetry. Conversely, owls represent wisdom in Western traditions but are sometimes seen as omens of death in African and Middle Eastern folklore, illustrating how cultural context shapes avian symbolism.

| Feature | Birds (Aves) | Mammals (Mammalia) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Covering | Feathers | Hair/Fur |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying (oviparous) | Live birth (viviparous), except monotremes |

| Feeding Young | No milk; regurgitation or direct feeding | Milk from mammary glands |

| Metabolism | High metabolic rate | Moderate to high |

| Respiratory System | Unidirectional airflow with air sacs | Tidal breathing (in-out lung flow) |

| Skeleton | Lightweight, pneumatic bones | Denser, solid bones |

Practical Guide to Birdwatching: Tips for Observing Avian Life

For those interested in observing birds firsthand, birdwatching (or birding) offers an accessible way to engage with nature. Whether you're exploring urban parks or remote wilderness areas, understanding basic bird behavior enhances the experience. Start by investing in a quality pair of binoculars (8x42 magnification is ideal for beginners) and a regional field guide or mobile app like Merlin Bird ID or eBird.

The best times for birdwatching are early morning and late afternoon, when birds are most active in feeding and vocalizing. Spring and fall migrations present exceptional opportunities to see a wide variety of species. Look for habitat clues: woodpeckers prefer mature forests, shorebirds gather along wetlands, and raptors soar above open fields.

To attract birds to your yard, provide native plants, clean water sources, and appropriate feeders. Avoid pesticides, which reduce insect populations essential for many songbirds. Keep cats indoors to protect local bird populations—domestic cats are a leading cause of bird mortality in residential areas.

Common Misconceptions About Birds

Several myths persist about birds, often blurring the line between fact and fiction. One widespread belief is that mother birds will reject their chicks if touched by humans. In reality, most birds have a poor sense of smell and will not abandon offspring due to human scent. However, unnecessary handling should still be avoided to prevent stress or injury.

Another misconception is that all birds migrate. While many species do undertake long-distance journeys, others remain in the same region year-round. Resident birds like cardinals, chickadees, and pigeons have adapted to survive cold winters with sufficient food and shelter.

Some people assume flightless birds like ostriches or penguins aren’t ‘true’ birds. But despite losing the ability to fly, these species retain all defining avian traits—feathers, egg-laying, and skeletal features—confirming their classification within Aves.

How to Verify Avian Information Reliably

With abundant misinformation online, it's essential to consult authoritative sources when learning about birds. Reputable organizations such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Audubon Society, and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) provide scientifically validated data on bird species, behaviors, and conservation status.

When researching specific questions—such as whether certain birds are endangered or where to spot rare species—cross-reference multiple peer-reviewed sources. Citizen science platforms like eBird allow users to contribute observations while accessing real-time distribution maps based on verified sightings.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are bats birds?

- No, bats are mammals. Although they can fly, they give birth to live young, have fur, and produce milk—all mammalian traits. Birds, in contrast, lay eggs and have feathers.

- Do any birds give milk?

- No bird produces milk like mammals. However, some birds like pigeons and flamingos secrete a nutritious substance called 'crop milk' from their digestive tract to feed chicks. It is not true milk and lacks the composition of mammalian milk.

- Can birds think and learn?

- Yes, many birds—especially corvids (crows, ravens) and parrots—demonstrate advanced cognitive abilities, including problem-solving, tool use, and social learning, rivaling primates in some tests.

- Why do people confuse birds with mammals?

- The confusion arises because both groups are warm-blooded and care for their young. However, reproductive methods, body coverings, and skeletal structures clearly differentiate them.

- Is a penguin a bird or a mammal?

- Penguins are birds. They have feathers, lay eggs, and are classified under Aves. Despite being flightless and living in aquatic environments, they share all key avian characteristics.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4