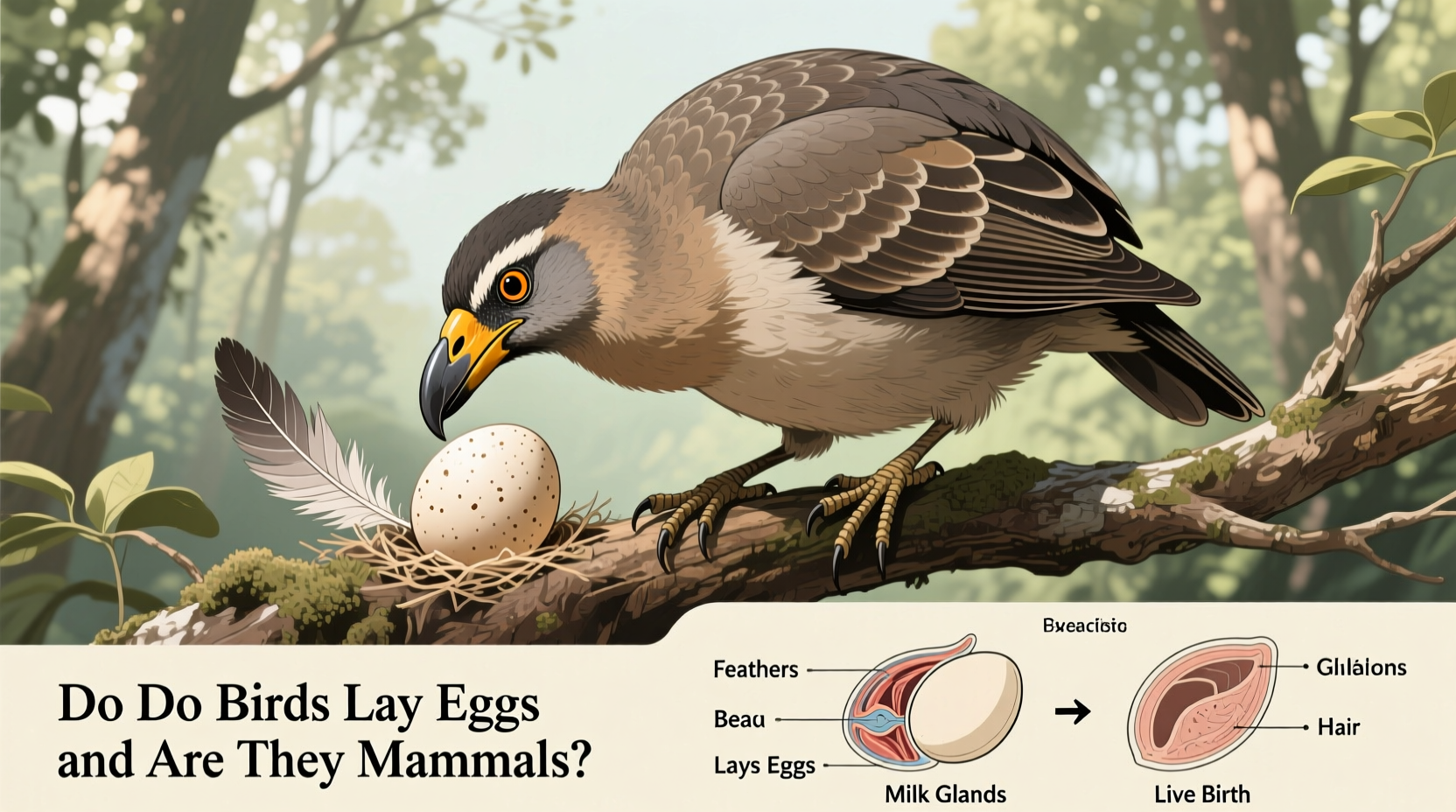

Birds are not mammals; they are a distinct class of vertebrate animals known as Aves. One of the most frequently asked questions in ornithology and general biology is do do birds share characteristics with mammals? While both birds and mammals are warm-blooded, they differ significantly in reproduction, anatomy, and evolutionary lineage. Birds lay eggs, have feathers, and possess beaks—none of which are defining traits of mammals. This fundamental distinction helps clarify a common misconception rooted in superficial similarities, such as endothermy and parental care behaviors.

Understanding the Classification of Birds

The biological classification of living organisms places birds in the class Aves, separate from mammals, which belong to the class Mammalia. Both groups fall under the phylum Chordata due to their possession of a notochord at some stage in development. However, their divergence becomes clear when examining key physiological and reproductive traits.

One natural longtail keyword variant that reflects user search intent is do do birds lay eggs and how does that differentiate them from mammals? The answer lies in reproductive strategy: nearly all birds reproduce by laying hard-shelled eggs, whereas most mammals give birth to live young (with exceptions like the platypus). Additionally, birds lack mammary glands—the defining feature of mammals—and instead feed their chicks through regurgitation or direct provisioning of food.

Anatomical Differences Between Birds and Mammals

Beyond reproduction, several anatomical features distinguish birds from mammals:

- Feathers vs. Hair: Feathers are unique to birds and serve functions including flight, insulation, and display. Mammals, on the other hand, are characterized by hair or fur.

- Skeleton and Flight Adaptations: Birds have lightweight, hollow bones and a fused skeletal structure optimized for flight. Most mammals have denser bones adapted for terrestrial locomotion.

- Respiratory System: Birds possess a highly efficient one-way airflow respiratory system with air sacs, allowing continuous oxygen uptake during both inhalation and exhalation—a significant advantage over the tidal breathing system of mammals.

- Heart Structure: Both birds and mammals have four-chambered hearts, contributing to their high metabolic rates. However, this similarity evolved independently through convergent evolution rather than shared ancestry.

These differences underscore why, despite both being warm-blooded vertebrates, birds are not classified as mammals. Understanding these distinctions helps address queries like do do birds have sweat glands?—they do not. Instead, birds regulate body temperature through panting, gular fluttering, and behavioral adaptations such as seeking shade.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds hold profound symbolic meaning across cultures, often representing freedom, transcendence, or spiritual messengers. In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird—a precursor to the Greek phoenix—symbolized rebirth and the sun. Native American traditions frequently view eagles as sacred beings connecting earth and sky. Similarly, in Christianity, the dove represents the Holy Spirit, peace, and purity.

The question do do birds carry messages between worlds? resonates deeply in mythological contexts. For example, ravens appear in Norse mythology as Odin’s spies, bringing knowledge from distant realms. In Celtic lore, cranes were believed to carry souls to the afterlife. These narratives reflect humanity's enduring fascination with avian flight as a metaphor for liberation and higher consciousness.

This cultural symbolism influences modern language and psychology. Phrases like “free as a bird” or “bird’s-eye view” derive from observations of avian behavior. Even in dreams, birds often symbolize aspirations, clarity, or emotional release. Recognizing these layers enriches our understanding beyond mere taxonomy.

Evolutionary Origins: How Birds Descended from Dinosaurs

A pivotal discovery in paleontology confirms that birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Fossils such as Archaeopteryx, dating back approximately 150 million years, exhibit both reptilian and avian traits—teeth, long bony tails, and feathered wings. More recent finds like Microraptor and Anchiornis further solidify the dinosaur-bird link.

Key evolutionary developments include:

- The gradual modification of forelimbs into wings.

- The loss of teeth and development of beaks.

- The refinement of feathers from simple filaments used for insulation to complex structures enabling powered flight.

This evolutionary journey answers another variation of the core query: do do birds come from dinosaurs? Yes—they are considered living dinosaurs by many scientists, specifically members of the clade Maniraptora. This reclassification has transformed public perception and scientific education about bird origins.

Practical Guide to Birdwatching: Tips for Observers

For those interested in observing birds firsthand, birdwatching offers an accessible way to engage with nature. Whether you're exploring urban parks or remote wetlands, here are essential tips to enhance your experience:

- Use Binoculars: A good pair with 8x42 magnification provides optimal balance between field of view and detail.

- Carry a Field Guide: Choose region-specific guides or use apps like Merlin Bird ID or eBird to identify species based on appearance, song, and habitat.

- Visit During Peak Activity Times: Early morning (dawn to mid-morning) and late afternoon offer the highest bird activity levels.

- Dress Appropriately: Wear muted colors to avoid startling birds and bring weather-appropriate clothing.

- Practice Ethical Observation: Maintain distance, avoid playback calls excessively, and never disturb nests.

Urban dwellers can still participate effectively. Common city-adapted species include pigeons (Columba livia), house sparrows (Passer domesticus), and American robins (Turdus migratorius). Learning their calls enhances detection even when visibility is low.

Regional Variations in Bird Diversity and Behavior

Bird distribution varies widely by geography, climate, and ecosystem. Tropical regions like the Amazon Basin host the greatest avian diversity, with over 1,300 species recorded. In contrast, polar areas support fewer species adapted to extreme cold, such as snow petrels and emperor penguins.

Migratory patterns also differ regionally. North American warblers travel thousands of miles between breeding grounds in Canada and wintering sites in Central and South America. Meanwhile, European swallows migrate from Scandinavia to sub-Saharan Africa.

To understand local patterns, consult resources like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology or national wildlife agencies. Ask yourself: do do birds migrate in my area and when? Migration timing depends on latitude, altitude, and seasonal changes in food availability. Spring migrations typically occur March–May in the Northern Hemisphere; fall migrations span August–November.

| Region | Notable Species | Migratory Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Bald Eagle, Northern Cardinal | Seasonal north-south migration |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | African Grey Parrot, Ostrich | Largely resident, some altitudinal movement |

| Southeast Asia | Hornbills, Pittas | Partial migration, monsoon-driven |

| Australia | Kookaburra, Emu | Mainly non-migratory |

Common Misconceptions About Birds

Several myths persist about bird biology and behavior:

- Misconception: All birds can fly.

Reality: Over 60 extant species are flightless, including ostriches, kiwis, and penguins—each adapted to specific ecological niches. - Misconception: Birds abandon chicks if touched by humans.

Reality: Most birds have a poor sense of smell and will not reject offspring due to human scent. However, unnecessary handling should still be avoided to prevent stress. - Misconception: Birds are simple-minded.

Reality: Many species demonstrate advanced cognition. Crows, parrots, and jays exhibit tool use, problem-solving, and memory skills rivaling primates.

Addressing these misunderstandings improves public appreciation and conservation efforts. Another relevant longtail query is do do birds feel emotions? Evidence suggests birds experience fear, pleasure, and social bonding, particularly in species with complex social structures.

Conservation Challenges Facing Birds Today

Bird populations face growing threats from habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and invasive species. According to the IUCN Red List, over 1,400 bird species are threatened with extinction. Iconic examples include the critically endangered Kakapo of New Zealand and the Philippine Eagle.

Effective conservation strategies include:

- Protecting critical habitats through national parks and wildlife refuges.

- Reducing pesticide use that harms insect-dependent birds.

- Installing bird-safe glass on buildings to prevent window collisions—an estimated cause of up to one billion bird deaths annually in the U.S.

- Supporting international agreements like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Individuals can contribute by participating in citizen science projects such as the Christmas Bird Count or Project FeederWatch, reporting sightings, and advocating for green policies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Are birds reptiles? Genetically and evolutionarily, birds are considered a subgroup of reptiles due to their descent from dinosaurs, though colloquially they are treated separately.

- Do birds sleep? Yes, birds sleep, often with one hemisphere of the brain awake (unihemispheric slow-wave sleep), especially during migration or in vulnerable environments.

- Can birds recognize humans? Some species, especially corvids and parrots, can recognize individual human faces and voices.

- Why don’t birds get electrocuted on power lines? They don’t complete an electrical circuit unless touching another wire or grounded object simultaneously.

- Is a bat a bird? No. Bats are mammals capable of true flight, distinguished by fur, live birth, and milk production.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4