If you're asking, 'Do I have bird flu?' the short and clear answer is: it's highly unlikely unless you've had direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily affects birds — especially wild waterfowl and domestic poultry — and only rarely spreads to humans. The natural longtail keyword variation 'can humans get bird flu from backyard chickens' reflects a common concern among backyard bird keepers and rural residents. While human cases are uncommon, they can occur, particularly in individuals exposed to sick or dead birds, live bird markets, or unregulated poultry farms.

Understanding Avian Influenza: What It Is and How It Spreads

Bird flu is caused by strains of the influenza A virus, most commonly subtypes H5 and H7. These viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks, geese, and swans, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. However, when introduced into domestic poultry flocks — such as chickens, turkeys, and quails — the disease can spread rapidly and cause high mortality rates.

The transmission to humans typically happens through close and prolonged contact with infected birds or their droppings, saliva, or contaminated surfaces. There is currently no widespread human-to-human transmission of bird flu, which limits its pandemic potential. Still, public health officials monitor outbreaks closely because of the risk that the virus could mutate into a form more easily transmissible between people.

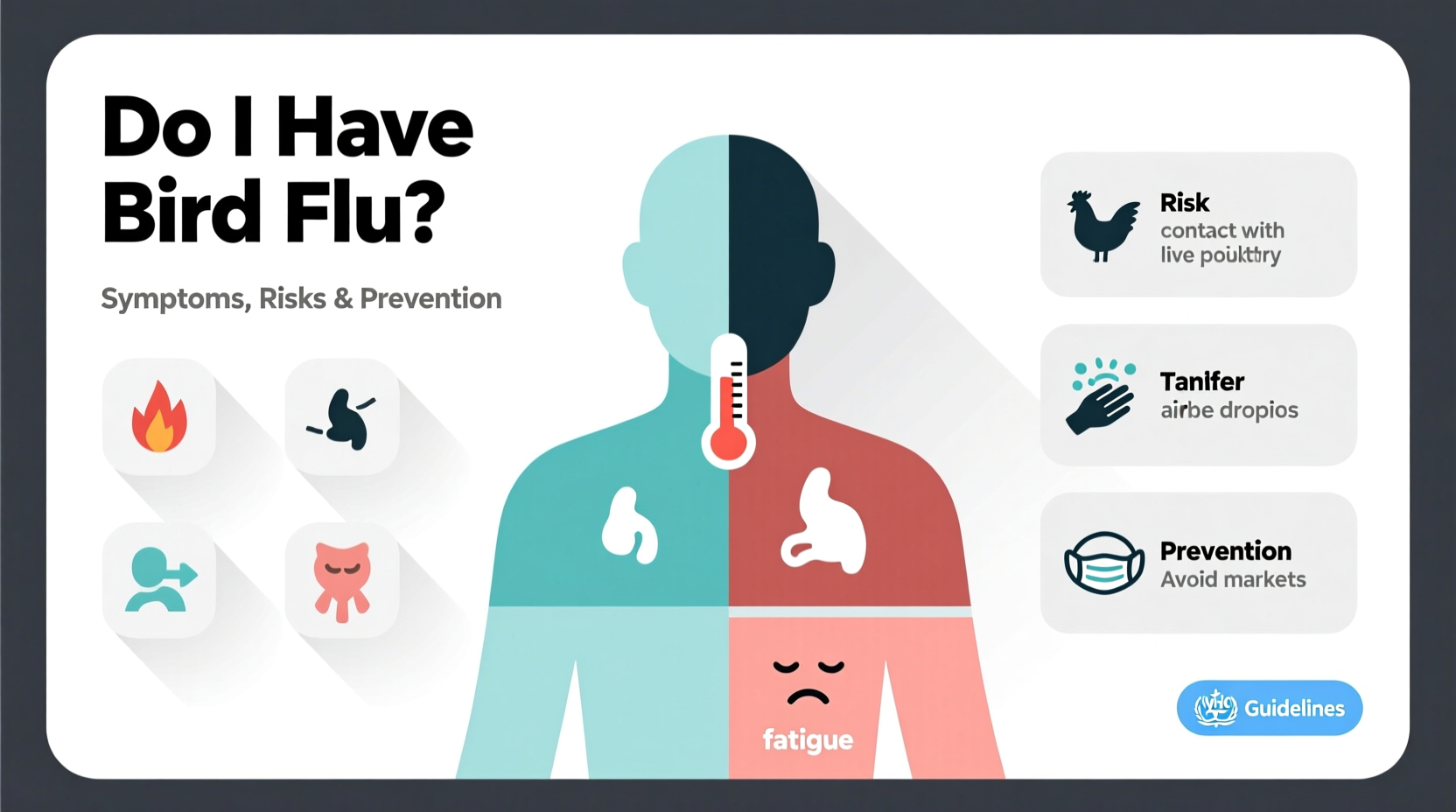

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Humans

While rare, human infections with avian influenza can lead to serious illness. Symptoms may appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure and can range from mild to severe. Common signs include:

- Fever (often high)

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Headache

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Conjunctivitis (pink eye), especially in some H7 strains

In severe cases, bird flu can progress to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and even death. Older adults and those with underlying health conditions are at higher risk for complications.

How to Know If You Have Bird Flu: Diagnosis and Testing

If you’ve been near sick or dead birds and begin experiencing flu-like symptoms, it’s important not to panic — but do seek medical attention promptly. Your healthcare provider will evaluate your symptoms and exposure history. Diagnostic testing usually involves collecting respiratory samples (such as nasal or throat swabs) within the first few days of symptom onset.

These samples are tested using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays that can detect avian influenza RNA. In some cases, blood tests may be used to confirm infection retrospectively. Rapid flu tests available in clinics typically do not distinguish bird flu from seasonal influenza, so specific lab-based testing is required for confirmation.

Who Is at Risk of Contracting Bird Flu?

Most people are not at significant risk of contracting bird flu. However, certain groups face higher exposure due to their occupations or activities:

- Poultry farmers and farm workers

- Veterinarians and animal health technicians

- Wildlife biologists and bird researchers

- People involved in culling operations during outbreaks

- Travelers visiting areas with active bird flu outbreaks, especially live bird markets

Backyard chicken owners should also remain vigilant, especially if wild birds frequent their property. Practices such as wearing gloves and masks while cleaning coops, avoiding contact with wild birds, and reporting sick or dead poultry to local authorities can reduce risk significantly.

Prevention: How to Protect Yourself From Bird Flu

There is currently no commercially available vaccine for the general public to prevent bird flu, although candidate vaccines are developed and stockpiled for potential pandemic use. The best protection lies in preventive measures, especially for those in high-risk settings.

Key prevention strategies include:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds, especially in regions reporting outbreaks.

- Wear protective clothing (gloves, masks, goggles) when handling birds or cleaning enclosures.

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after any bird contact.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly — the virus is destroyed at normal cooking temperatures (165°F or 74°C).

- Report clusters of dead wild birds to local wildlife or agricultural agencies.

- Stay informed about bird flu activity in your region via public health advisories.

Bird Flu Outbreaks: Geographic and Seasonal Trends

Bird flu outbreaks occur globally and tend to follow migratory bird patterns. In North America, increased cases are often reported in late fall and winter, coinciding with waterfowl migration. Europe, Asia, and Africa also experience seasonal surges, particularly in countries where backyard poultry farming is common and biosecurity measures may be limited.

In recent years, the H5N1 strain has spread widely among wild birds and poultry across dozens of countries. As of 2024, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) continue to track outbreaks in commercial and backyard flocks. Some states have imposed temporary restrictions on bird gatherings, such as poultry shows and swap meets, to limit transmission.

| Region | Common Strains | Peak Season | Human Cases (2020–2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | H5N1, H7N8 | October–March | 5 confirmed |

| Europe | H5N1, H5N8 | November–April | 12 confirmed |

| Asia | H5N1, H7N9 | Year-round, peaks in winter | Over 200 (mostly China, prior to 2023) |

| Africa | H5N1 | Variable | 8 confirmed |

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza that can lead to unnecessary fear or poor decision-making:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized egg products are safe. The virus is killed by heat. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily from person to person.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented. - Myth: All dead birds are a sign of bird flu.

Fact: Many factors — including poisoning, trauma, or other diseases — can kill birds. Always report findings to authorities rather than assuming cause. - Myth: There’s nothing you can do to protect your flock.

Fact: Biosecurity measures like fencing, limiting visitors, and isolating new birds can greatly reduce risk.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu Exposure

If you believe you’ve been exposed to bird flu — for example, after handling a sick bird without protection — take these steps immediately:

- Contact your healthcare provider and describe your exposure.

- Monitor yourself for fever, cough, or breathing difficulties for up to 10 days.

- Avoid close contact with others, especially vulnerable individuals.

- Follow public health guidance regarding quarantine or antiviral treatment.

- Report sick or dead birds to your state’s department of agriculture or wildlife agency.

In some cases, doctors may prescribe antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) as a preventive measure, especially for high-risk exposures. Early treatment improves outcomes if infection does occur.

Differences Between Bird Flu and Seasonal Flu

It’s easy to confuse bird flu with regular seasonal influenza, but there are key differences:

- Origin: Bird flu originates in birds; seasonal flu circulates among humans.

- Transmission: Bird flu requires animal contact; seasonal flu spreads person-to-person.

- Vaccination: Annual flu shots protect against seasonal strains but not avian influenza.

- Severity: Bird flu tends to cause more severe respiratory illness compared to typical flu.

If you’re experiencing flu symptoms during bird flu outbreak periods, your doctor may consider both possibilities based on your travel and exposure history.

Global Surveillance and Public Health Response

Organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and WOAH maintain global surveillance systems to detect and respond to avian influenza outbreaks. These networks help identify emerging strains, assess pandemic risk, and guide control measures such as poultry vaccination, movement restrictions, and public education.

In the U.S., the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) leads outbreak response, including testing, depopulation of affected flocks, and compensation programs for farmers. Transparency and rapid reporting are essential to contain spread and maintain consumer confidence in poultry products.

FAQs About Bird Flu and Human Health

- Can I get bird flu from watching birds in my backyard?

- No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected birds or their secretions.

- Is there a bird flu vaccine for humans?

- There is no routine vaccine for the public, but experimental vaccines are stored for emergency use in case of a pandemic.

- Are pet birds at risk of getting bird flu?

- Yes, especially if housed outdoors and exposed to wild birds. Indoor housing and strict hygiene reduce risk.

- Has bird flu ever caused a pandemic?

- No, despite several outbreaks, bird flu has not achieved sustained human-to-human spread needed for a pandemic.

- Should I stop feeding wild birds to avoid bird flu?

- Not necessarily, but clean feeders regularly with a 10% bleach solution and discontinue feeding if sick or dead birds are seen nearby.

In summary, while the question 'do I have bird flu' may arise during outbreaks or after bird contact, actual human cases remain extremely rare. Awareness, proper hygiene, and timely medical consultation are your best defenses. By understanding the facts, dispelling myths, and following recommended precautions, you can safely enjoy bird-related activities without undue fear.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4