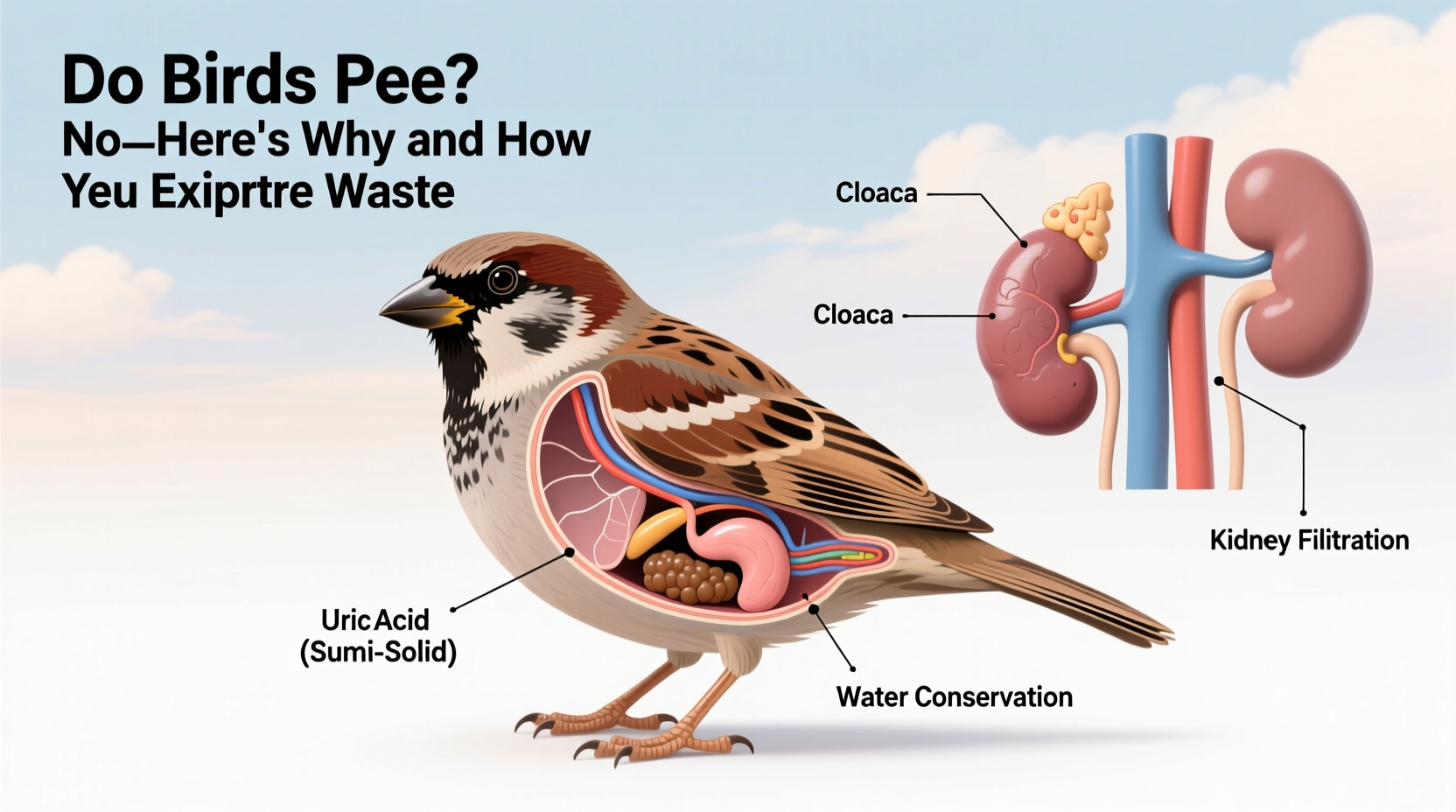

No, birds do not pee in the way mammals do. Instead of producing liquid urine, birds excrete nitrogenous waste in the form of uric acid, which appears as a white, paste-like substance often seen alongside their droppings. This unique adaptation answers the common question: does a bird pee, and reveals how avian physiology has evolved for flight efficiency and water conservation. Unlike mammals, which flush out urea through urine, birds combine metabolic waste with feces in a single exit—the cloaca—resulting in the familiar splats often found under roosts or nests.

The Science Behind Avian Waste: Why Birds Don’t Pee

Birds lack a bladder and do not produce liquid urine because their bodies convert ammonia—a toxic byproduct of protein metabolism—into uric acid instead of urea. This process is more energy-intensive than urea production but offers critical survival advantages. Uric acid is largely insoluble in water, allowing birds to excrete it with minimal fluid loss. This adaptation is essential for animals that fly, where carrying excess water weight would be inefficient.

The absence of a urinary bladder also reduces overall body mass, further supporting the demands of flight. In fact, most birds have only one ovary and a highly compact digestive system—all evolutionary trade-offs to remain lightweight and aerodynamic. The excretion process occurs in the kidneys, where nitrogenous waste is filtered from the blood. Rather than being dissolved in water and sent to a bladder, the uric acid crystallizes and travels through the ureters into the cloaca.

What You’re Seeing: Decoding Bird Droppings

If you’ve ever noticed white caps on bird droppings beneath a tree or on your car, that’s the uric acid portion—often mistaken for 'bird pee.' The typical bird dropping consists of three components:

- Fecal matter: The dark, solid portion derived from digested food.

- Uric acid: The chalky white or off-white paste that replaces liquid urine.

- Mucus: A clear gel-like coating that helps bind the waste together during expulsion.

This combined waste exits through the cloaca, a multi-purpose opening used for excretion, reproduction, and egg-laying. Because everything passes through the same channel, birds cannot separate urination from defecation—another reason why the concept of 'peeing' doesn’t apply to them.

| Component | Description | Function/Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Matter | Dark, solid core | Undigested food residue from intestines |

| Uric Acid Paste | White or creamy cap | Nitrogenous waste from kidneys; replaces urine |

| Mucus Layer | Transparent film | Lubricates waste for easier passage through cloaca |

Evolutionary Advantages of Not Peing

The avian method of waste elimination isn't just a biological curiosity—it's a finely tuned adaptation shaped by millions of years of evolution. Several key benefits arise from not peeing:

- Weight Reduction: Eliminating the need for a bladder and reducing water retention significantly cuts body mass, crucial for powered flight.

- Water Conservation: Birds, especially those in arid environments (like desert-dwelling larks or seabirds), must conserve every drop. Uricotelism (excreting uric acid) minimizes dehydration risk.

- Egg Safety: In developing embryos inside eggs, toxic ammonia could damage tissues. By converting nitrogen waste into inert uric acid crystals stored in the allantois, birds protect their young during incubation.

- Hygiene and Nest Maintenance: Producing dry, semi-solid waste allows parent birds to remove fecal sacs from nests easily, reducing odor and parasite buildup.

This system is so effective that it's shared among other uricotelic animals, including reptiles and insects, suggesting convergent evolution under similar environmental pressures.

Comparative Physiology: Birds vs. Mammals vs. Reptiles

To better understand whether a bird pees, it helps to compare excretory systems across animal classes:

- Mammals: Are ureotelic—they convert ammonia into urea, which dissolves in water to form liquid urine. Stored in the bladder and expelled periodically.

- Birds & Reptiles: Are uricotelic—produce uric acid paste with very little water loss. No bladder; waste moves directly from kidneys to cloaca.

- Aquatic Animals: Many fish are ammonotelic—excrete ammonia directly into surrounding water, which dilutes the toxin instantly.

This contrast highlights how habitat and physiology shape excretion strategies. For instance, a pigeon flying over a city doesn’t have access to constant water sources, making water-efficient waste processing vital for survival.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Waste

While scientifically unremarkable, bird droppings carry surprising cultural weight around the world. In several European countries, being 'blessed' by a bird is considered good luck—possibly because such events are rare and unpredictable, much like fortune itself. In Italy, people may joke about winning the lottery after a bird strike, while in parts of Asia, it’s seen as a sign of impending prosperity.

Conversely, in urban settings, bird waste is often viewed as a nuisance due to its corrosive effect on paint and building materials. Yet even here, there’s irony: the very adaptation that enables flight (uric acid excretion) leads to aesthetic challenges for humans sharing space with birds.

From an ecological standpoint, bird droppings play important roles. Guano—accumulated seabird excrement—is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, historically mined as fertilizer. Islands like Ichaboe off Namibia or coastal cliffs in Peru host massive colonies whose collective waste supports entire ecosystems and agriculture.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Pet Owners

Understanding how birds eliminate waste can enhance both field observation and avian care at home. For birdwatchers, droppings offer clues about species presence, diet, and roosting patterns. A concentration of white-capped splats beneath a tree might indicate regular owl perching, while streaked deposits on rocks near shorelines suggest gull activity.

For pet bird owners—especially those keeping parrots, canaries, or finches—monitoring droppings is essential for health assessment. Normal droppings should have a consistent ratio of dark feces to white urate. Changes such as:

- Excessively watery discharge (polyuria)

- Discolored urates (yellow, green, or brown)

- Lack of solid fecal component

...can signal illness, including liver disease, infection, or kidney dysfunction. Unlike in mammals, increased fluid intake doesn’t lead to more 'peeing'—so any apparent increase in moisture likely reflects pathology, not hydration.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Peeing

Several myths persist about avian excretion, fueled by casual observation and linguistic imprecision:

- Myth: The white part of bird poop is urine.

Truth: While functionally analogous to urine, it’s chemically distinct—uric acid, not liquid urea solution. - Myth: Baby birds pee and poop separately.

Truth: Nestlings produce fecal sacs—mucous-coated packages containing both feces and urates—for parents to remove cleanly. - Myth: Birds drink less because they don’t pee.

Truth: Birds do drink water, but their efficient kidneys reabsorb most of it. Hummingbirds, for example, consume nectar daily but still maintain low water turnover in waste.

Regional and Species Variations in Waste Output

While all birds follow the same basic excretory model, variations exist based on diet and environment:

- Carnivorous birds (e.g., hawks, owls): Produce thicker, whiter urate deposits due to high protein intake and thus higher nitrogen load.

- Herbivorous birds (e.g., geese, pigeons): Have bulkier, greener fecal matter with slightly less prominent urates.

- Seabirds (e.g., albatrosses, gulls): Possess salt glands above the eyes that excrete excess sodium chloride, expelled via sneezing. This is separate from kidney function but complements water balance.

In extreme climates, these differences become more pronounced. Desert quails may produce almost crystalline uric acid, while rainforest toucans—with greater water availability—have slightly moister droppings, though never truly liquid urine.

How to Observe and Record Avian Waste Patterns Ethically

Birdwatchers interested in behavior or population studies can use droppings as non-invasive indicators. To do so responsibly:

- Wear gloves when handling or collecting samples to avoid pathogens like histoplasmosis or salmonella.

- Photograph droppings in situ with a scale reference (e.g., ruler or coin) for later analysis.

- Note location, substrate, and frequency—repeated markings on power lines or statues may reveal territorial habits.

- Never disturb nesting sites to examine waste; observe from a distance.

- Report unusual findings (e.g., bloody droppings, mass die-offs) to local wildlife authorities.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do baby birds pee?

- No, hatchlings excrete waste in fecal sacs, which contain both feces and uric acid. Parents remove these sacs to keep nests clean.

- Why is bird poop white?

- The white part is uric acid, the bird’s version of urine. It’s a paste formed from nitrogenous waste and conserves water.

- Can birds get urinary tract infections?

- Birds don’t have urinary tracts like mammals, but they can suffer kidney disease, which affects urate production and appearance.

- Is bird poop harmful to humans?

- Fresh droppings pose low risk, but dried guano can harbor fungi causing respiratory illnesses. Always wash hands after outdoor contact.

- Do all birds excrete the same way?

- Yes, all modern birds use the cloaca and excrete uric acid. Differences lie in volume, color, and consistency based on diet and species.

In conclusion, the answer to does a bird pee is definitively no—not in the mammalian sense. Instead, birds have evolved a sophisticated, water-efficient system that merges waste elimination with the demands of flight and survival. Whether you're a curious observer, a backyard birder, or a dedicated ornithologist, recognizing this distinction deepens appreciation for avian biology and the remarkable adaptations hidden in plain sight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4