Birds do not pee in the way mammals do. Instead of producing liquid urine, birds excrete nitrogenous waste primarily in the form of uric acid, which appears as a white paste mixed with their feces. This efficient biological adaptation answers the common question: do birds pee and poop at the same time? Yes—they do, and this is due to their specialized excretory system that conserves water, a crucial advantage for flight and survival. Understanding how birds get rid of waste without peeing reveals fascinating insights into avian physiology, evolution, and adaptation.

The Avian Excretory System: No Bladder, No Liquid Urine

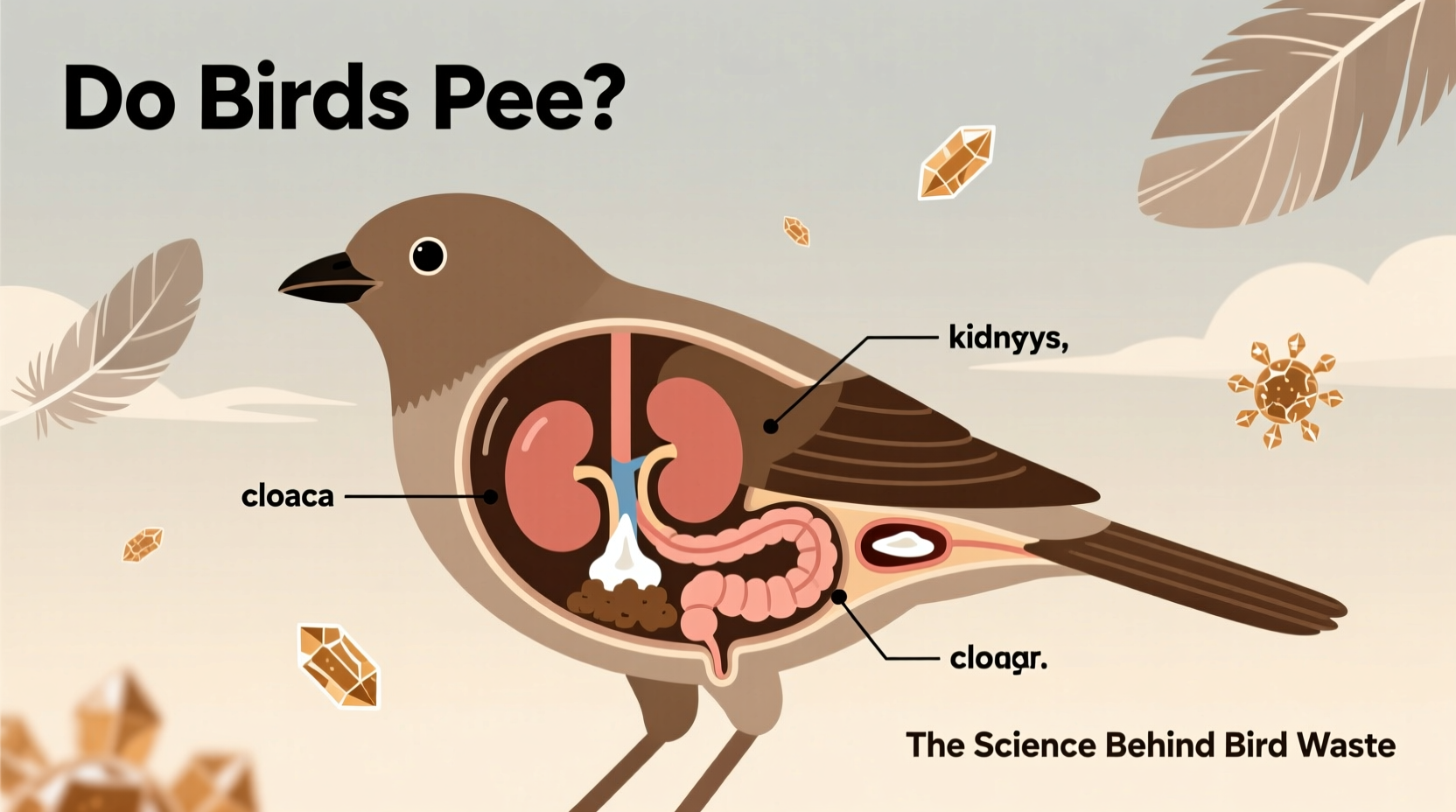

Unlike mammals, birds lack a urinary bladder and do not produce liquid urine. In humans and most mammals, the kidneys filter blood and produce urea, which dissolves in water to form urine stored in the bladder before excretion. Birds, however, convert nitrogenous waste into uric acid—a less toxic compound that requires minimal water to excrete. This process occurs in the kidneys, but instead of releasing it as liquid, the uric acid precipitates into a semi-solid, chalky white substance.

This white component often seen coating bird droppings is not fecal matter but the equivalent of 'urine' in birds. It exits the body through the cloaca—the single posterior opening used for excretion, reproduction, and egg-laying—simultaneously with digested waste. Therefore, when you observe a bird defecating, it is expelling both metabolic waste products at once. This leads many people to ask, why don’t birds pee like humans? The answer lies in evolutionary pressures favoring weight reduction and water conservation.

Why Don’t Birds Have a Bladder?

The absence of a urinary bladder in birds is an adaptation tied directly to flight efficiency. Carrying excess fluids would increase body mass, making sustained flight more energetically costly. By eliminating the need to store liquid urine, birds reduce weight and streamline internal anatomy. Additionally, most birds obtain limited access to fresh water, especially those living in arid environments or migrating over long distances. Excreting uric acid instead of urea allows them to conserve precious water resources.

Uricotelic animals (those that excrete uric acid) include reptiles and insects, placing birds within a broader evolutionary context. This trait likely originated in their reptilian ancestors, further supporting the close phylogenetic relationship between modern birds and dinosaurs. So while birds don’t pee like mammals, their method of waste removal reflects deep evolutionary roots and ecological specialization.

What Does Bird Poop Actually Consist Of?

A typical bird dropping consists of three components:

- Fecal portion: Dark, solid material composed of digested food remnants.

- Uric acid portion: The white, pasty coating that represents the excreted nitrogenous waste (avian 'urine').

- Mucus lining: A clear gel-like substance that may surround the dropping, aiding in passage through the cloaca.

The ratio of these components can vary depending on diet, hydration levels, and species. For example, seed-eating birds like pigeons tend to produce droppings with a higher proportion of white uric acid, while fruit-eating birds such as toucans may have darker, looser stools due to increased water intake.

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Feces | Solid, dark-colored waste from digestion | Eliminates undigested food particles |

| Uric Acid | White, creamy substance | Excretes nitrogen waste with minimal water loss |

| Mucus | Clear or translucent gel | Lubricates cloacal passage |

How Do Different Bird Species Handle Waste?

While all birds share the basic mechanism of uric acid excretion, there are variations across species based on habitat, diet, and behavior.

Marine birds, such as gulls and albatrosses, consume large amounts of saltwater. To manage osmotic balance, they possess specialized nasal salt glands that excrete excess sodium chloride through sneezing or nasal discharge. While this is separate from kidney function, it complements their low-water excretion strategy by reducing renal stress.

Raptors and scavengers, including eagles and vultures, often regurgitate indigestible materials like bones and fur in the form of pellets. However, their actual waste still follows the standard avian pattern—dark fecal matter coated in white uric acid. Observers sometimes mistake pellet casting for defecation, leading to confusion about how often birds actually poop.

Pelagic birds (those spending much of their lives at sea) have highly concentrated excretions, minimizing any unnecessary water loss. Conversely, tropical frugivores like parrots may defecate more frequently due to high water content in their diets, though they still avoid producing liquid urine.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Waste

Several myths persist about bird excretion, largely because their droppings differ so dramatically from mammalian waste. One widespread misconception is that birds don’t poop inside nests. While adult birds typically avoid defecating in the nest to maintain hygiene, nestlings eliminate waste in special sacs called fecal sacs, which parents remove and discard away from the nest. This behavior helps prevent odor buildup and reduces predation risk.

Another myth is that bird droppings are pure urine. As explained, the white part is uric acid—the functional equivalent of urine—but it is always combined with fecal matter during expulsion. There is no separate stream of liquid waste, so asking can birds control when they pee? misunderstands avian biology; they cannot separate urination from defecation.

Some also believe that birds never urinate at all. This is inaccurate. They do excrete urinary waste—it’s just in a different physical form. Saying birds don’t pee is a simplification that overlooks the complexity of their excretory process.

Observational Tips for Birdwatchers

Understanding bird waste can enhance your observational skills in the field. Here are practical tips for interpreting droppings during birdwatching:

- Identify species by droppings: Large raptors leave sizable droppings with prominent white caps, while small songbirds produce tiny specks. Waterfowl droppings near ponds may appear more diluted due to aquatic feeding habits.

- Track feeding activity: Accumulated droppings under trees or roosting sites indicate regular use by certain species. The presence of berry seeds in fecal matter can reveal dietary preferences.

- Assess health: Abnormal droppings—such as completely watery, greenish, or blood-tinged excrement—may signal illness. Healthy bird waste should be firm with a distinct white uric acid cap.

- Avoid contamination: Always wash hands after handling bird feeders or cleaning areas with accumulated droppings. Bird waste can carry pathogens like Salmonella or Chlamydia psittaci, especially in urban settings.

Implications for Aviculture and Pet Birds

If you own a pet bird—such as a parakeet, cockatiel, or macaw—monitoring droppings is essential for assessing health. Changes in frequency, color, or consistency can be early warning signs. For instance:

- Increased urination-like appearance: If the white portion becomes runny or excessive, it could indicate kidney issues or dehydration.

- Green feces: Often linked to liver disease or diet changes (e.g., eating lots of leafy greens).

- Reddish tinge: May suggest blood in the droppings, requiring immediate veterinary attention.

Since pet birds cannot hold their pee (because they don’t produce liquid urine), owners should expect frequent elimination—sometimes every 10–15 minutes in small species. Training birds to go on command is possible using positive reinforcement, though it involves controlling defecation timing rather than urination.

Environmental and Cultural Perspectives

Bird droppings, known as guano, have played significant roles throughout human history. In pre-Columbian South America, Andean civilizations harvested seabird guano from coastal islands as a potent agricultural fertilizer. Its high nitrogen and phosphate content made it extremely valuable, leading to international trade conflicts in the 19th century—the so-called “Guano Wars” between Peru, Chile, and Bolivia.

Culturally, being hit by bird poop is considered lucky in many societies, symbolizing unexpected fortune. Conversely, in urban environments, bird waste poses maintenance challenges for buildings, vehicles, and public spaces. Understanding that birds don’t pee separately from pooping explains why cleanup requires removing both organic and mineral deposits.

Scientific Research and Ongoing Studies

Modern ornithologists continue studying avian excretion to understand metabolic rates, hydration status, and environmental adaptation. Non-invasive sampling of droppings allows researchers to analyze hormones, DNA, parasites, and diet composition without capturing or harming birds. These techniques are particularly useful in conservation biology, where monitoring endangered species must be as unobtrusive as possible.

Recent studies have explored how climate change affects water retention strategies in desert-dwelling birds. As temperatures rise and water sources diminish, species relying on uric acid excretion may face new physiological limits. Researchers are investigating whether some birds can adjust uric acid production under extreme heat stress.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do birds pee and poop out of the same hole?

- Yes, birds excrete both feces and uric acid through the cloaca, a multi-purpose opening used for digestion, reproduction, and waste elimination.

- Why is bird poop white?

- The white part is uric acid, the avian equivalent of urine. It forms a paste instead of liquid to conserve water.

- Can birds hold their pee?

- No, because birds don’t produce liquid urine. They continuously process waste, and elimination happens quickly after digestion.

- Is bird poop harmful to humans?

- Fresh bird droppings can carry bacteria, fungi, and viruses. While rare, diseases like histoplasmosis or psittacosis can be transmitted, so proper hygiene is important.

- Do baby birds pee?

- Nestlings excrete waste in fecal sacs, which parents remove. These sacs contain both fecal matter and uric acid, so yes—they eliminate waste, but not through separate peeing.

In conclusion, the question does birds pee has a nuanced answer rooted in comparative anatomy and evolutionary biology. Birds do not pee like mammals, but they do excrete urinary waste in the form of uric acid, which combines with feces and exits via the cloaca. This adaptation supports flight, conserves water, and reflects millions of years of evolution. Whether you're a casual observer, a dedicated birder, or a pet owner, understanding this unique system enhances appreciation for avian life and informs better care and observation practices.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4