Bird eggs are fertilized internally when a female bird mates with a male, allowing sperm to unite with an egg cell in her reproductive tract—a process known as internal fertilization. This key stage in avian reproduction typically occurs before the shell forms around the egg. Understanding how bird eggs are fertilized reveals not only the biological intricacies of bird reproduction but also offers insight into nesting behaviors, breeding seasons, and successful chick development. Unlike mammals, birds do not give birth to live young; instead, they lay eggs that have been fertilized inside the body and then incubated externally.

The Biology of Bird Reproduction

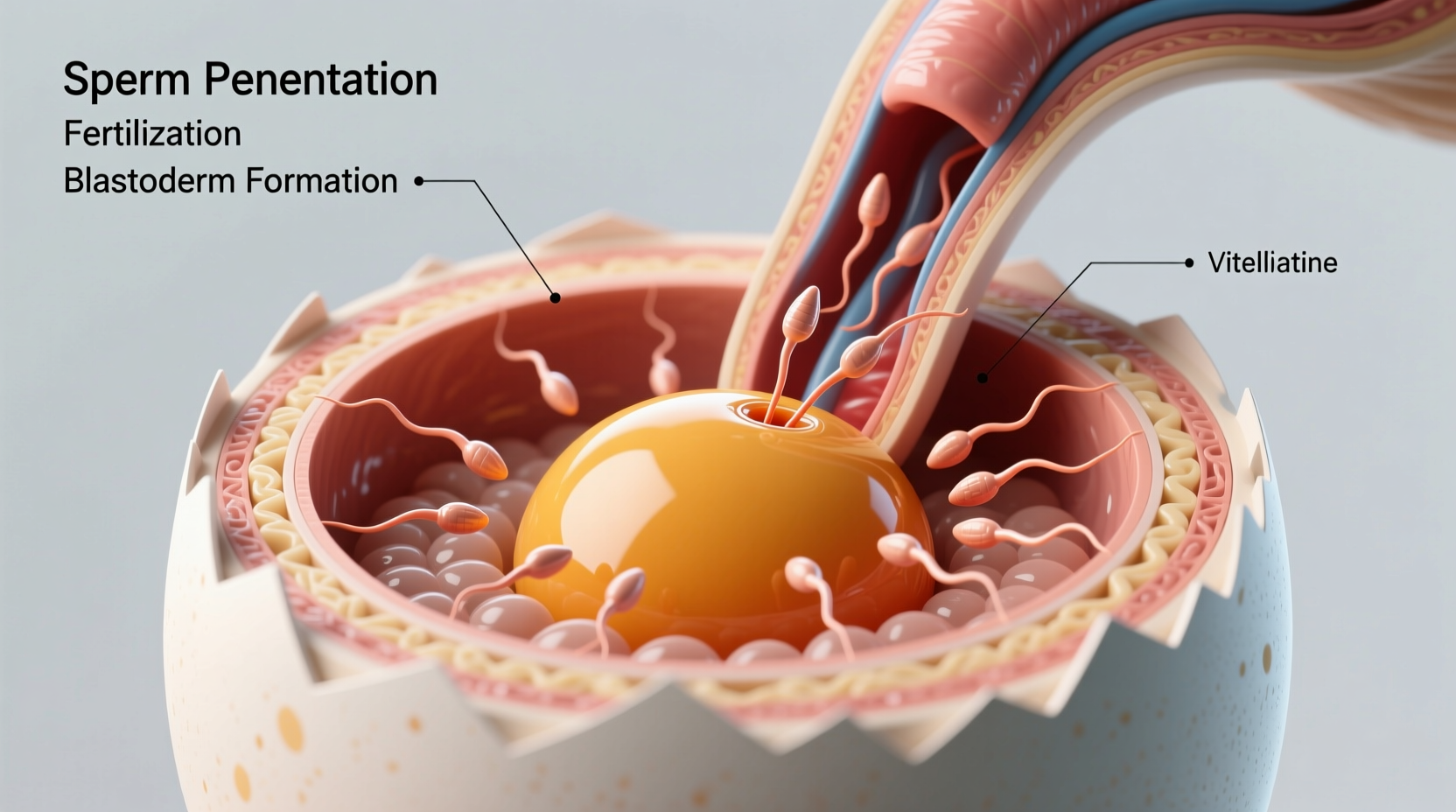

To fully grasp how bird eggs are fertilized, it's essential to understand the basic anatomy and physiology involved. Female birds possess a single functional ovary (usually on the left side), which produces yolks—each representing a potential egg. When a yolk matures, it is released into the oviduct, a long tube where several stages of egg formation occur over approximately 24 hours in most species.

Fertilization happens at the beginning of this journey, specifically in the infundibulum—the uppermost section of the oviduct. If mating has recently taken place, sperm stored from the male can fertilize the yolk within about 15 to 30 minutes after ovulation. Sperm can remain viable in the female’s reproductive tract for days or even weeks, depending on the species, enabling delayed fertilization.

After fertilization, the developing egg moves through the magnum (where albumen, or egg white, is added), then the isthmus (where shell membranes form), followed by the uterus (or shell gland), where the calcium carbonate shell is deposited over many hours. Finally, the completed egg passes through the cloaca and is laid.

Mating Behavior and Timing

Mating behavior plays a crucial role in ensuring successful fertilization. Most birds engage in courtship rituals that strengthen pair bonds and signal readiness to breed. These behaviors vary widely across species—from elaborate dances in cranes to colorful plumage displays in peacocks or song performances in nightingales.

Copulation itself is brief, often lasting just seconds. The male mounts the female, aligning their cloacas in what is known as a "cloacal kiss." During this contact, sperm is transferred from the male’s cloaca to the female’s. Birds lack external penises (with notable exceptions like ducks, geese, and some ratites), so this direct alignment is necessary for insemination.

The timing of mating relative to ovulation is critical. Since ovulation usually precedes egg-laying by about 24 hours, mating must occur close to this window to ensure sperm are present when the next yolk is released. In many species, pairs mate repeatedly during the breeding season to maximize chances of fertilization across multiple eggs.

Differences Between Fertilized and Unfertilized Eggs

A common misconception is that all bird eggs contain embryos. In reality, unfertilized eggs are common—especially in domesticated birds like chickens kept without roosters. These eggs consist of a yolk and surrounding nutrients but lack embryonic development because no sperm fused with the ovum.

In contrast, fertilized eggs contain genetic material from both parents. Under proper incubation conditions—either by a parent bird or in an artificial setting—a fertilized egg will begin cell division and eventually develop into a chick. You cannot visually distinguish a fertilized egg from an unfertilized one upon casual inspection unless candling (shining a bright light through the shell) reveals early signs of vascular development after a few days of incubation.

| Feature | Fertilized Egg | Unfertilized Egg |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of Embryo | Yes (if incubated) | No |

| Sperm Required | Yes | No |

| Laid by Hens Without Males? | No | Yes |

| Development Potential | Can hatch into chick | Cannot develop |

| Nutritional Value | Same as unfertilized | Identical |

Breeding Seasons and Environmental Triggers

Understanding when bird eggs get fertilized involves recognizing seasonal patterns influenced by environmental cues such as daylight length (photoperiod), temperature, food availability, and rainfall. Many temperate-zone birds breed in spring when resources are abundant and weather is favorable for raising chicks.

Tropical species may breed year-round or align with wet seasons. Some seabirds, like albatrosses, have extended breeding cycles lasting over a year, meaning fertilization events are spaced far apart. Migration also affects timing—birds often delay full sexual maturity until reaching breeding grounds.

Hormonal changes triggered by increasing daylight stimulate gonadal growth in both males and females. Testosterone levels rise in males, prompting territorial and mating behaviors, while estrogen increases in females, promoting yolk production and oviduct development.

Egg Incubation and Parental Care After Fertilization

Once a bird lays a fertilized egg, incubation begins—either immediately or after the clutch is complete, depending on the species. For example, robins start incubating after the last egg is laid to ensure synchronous hatching, while owls may begin after the first egg, leading to staggered hatchlings.

Incubation maintains optimal temperature (typically between 99°F and 102°F / 37°C–39°C) and humidity for embryo development. Parents rotate eggs regularly to prevent adhesion of the embryo to the shell membrane and ensure even heat distribution.

Most bird species share incubation duties, though roles vary. In eagles, females do most of the sitting, while males provide food. In penguins, males may incubate the egg on their feet under a brood pouch for weeks without eating.

Human Intervention: Artificial Incubation and Aviculture

In poultry farming and conservation programs, humans often use artificial incubators to control conditions precisely. Knowing how bird eggs become fertilized helps breeders manage mating pairs effectively and collect eggs at the right time.

For backyard chicken keepers, maintaining a ratio of one rooster per 8–10 hens ensures adequate fertilization without excessive aggression. Breeders of exotic birds, such as parrots or finches, may need to monitor mating closely and record dates to predict hatch windows accurately.

Artificial insemination is used in commercial turkey production due to selective breeding that has reduced natural mating efficiency. Semen is collected from males and introduced into females using specialized tools, mimicking natural fertilization internally.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Bird Eggs

Beyond biology, bird eggs carry rich cultural symbolism. Across civilizations, eggs represent renewal, fertility, and new beginnings. The Easter egg tradition, rooted in pre-Christian spring festivals and later adopted into Christian symbolism, reflects resurrection and rebirth.

In many indigenous cultures, bird eggs are seen as sacred gifts from nature. However, ethical concerns arise when wild bird eggs are collected, which is illegal in many countries—including under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act—to protect vulnerable species.

Artists and writers frequently use bird eggs as metaphors for fragility, potential, and hidden life. Their symmetrical shape and varied colors inspire scientific study and aesthetic appreciation alike.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Egg Fertilization

- Myth: All eggs laid by birds can hatch. Truth: Only fertilized eggs incubated properly can develop into chicks.

- Myth: Store-bought chicken eggs are fertilized. Truth: Commercially sold eggs come from hens not exposed to roosters and are therefore unfertilized.

- Myth: Touching an egg causes parents to reject it. Truth: Most birds have a poor sense of smell and won’t abandon eggs due to human scent.

- Myth: Eggs need to be fertilized every time they’re laid. Truth: One mating can result in multiple fertilized eggs over several days due to sperm storage.

Observing Fertilization and Breeding in Wild Birds

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, observing mating and nesting behaviors provides valuable insights into how bird eggs are made fertile. Look for signs such as increased singing, chasing flights, nest-building activity, and copulation attempts.

Use binoculars or spotting scopes to observe from a distance without disturbing birds. Note species-specific behaviors—for instance, male red-winged blackbirds display their shoulder patches to attract mates, while hummingbirds perform dramatic aerial dives.

If you find a nest, avoid frequent visits, as repeated disturbance can stress parents or attract predators. Never remove eggs or attempt to hatch them yourself—it’s illegal and unethical without proper permits.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you eat fertilized bird eggs?

- Yes, fertilized chicken eggs are safe to eat if refrigerated promptly. Development only begins under warm incubation conditions.

- How long does it take for a bird egg to be fertilized after mating?

- Fertilization occurs within 15–30 minutes after ovulation, which typically happens about 24 hours before laying.

- Do all birds lay fertilized eggs?

- No, only females that have mated with a male produce fertilized eggs. Those without access to males lay unfertilized ones.

- How can I tell if a wild bird egg is fertilized?

- You cannot tell visually. Candling after a few days of incubation may reveal blood vessels, indicating development.

- What happens if a fertilized egg isn’t incubated?

- Without consistent warmth, the embryo will not develop and will remain dormant until decomposition sets in.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4