Bird flu, or avian influenza, is generally not highly deadly to humans, but certain strains like H5N1 and H7N9 have shown high fatality rates when human infections do occur. While human cases are rare, the severity of illness can be extreme—particularly with direct exposure to infected poultry. Understanding how deadly bird flu is to humans requires examining both biological risk factors and real-world transmission patterns, including recent outbreaks in 2023–2024.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Strains

Avian influenza viruses belong to the influenza A family and primarily affect birds, especially wild waterfowl and domestic poultry. These viruses are categorized by surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Over a dozen H subtypes exist, but only a few—including H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2—have caused documented human infections.

The H5N1 strain first emerged in 1996 in geese in China and gained global attention during the 2003 outbreak in Southeast Asia. Since then, it has spread across continents via migratory birds. The virus is highly pathogenic in birds, often causing mass die-offs in poultry farms. Human infections remain uncommon but are concerning due to their severity.

In contrast, the H7N9 strain emerged in China in 2013 and initially showed less visible symptoms in birds, making surveillance more difficult. Despite lower mortality in birds, it caused severe respiratory illness in humans, with case fatality rates exceeding 40% during early waves.

How Deadly Is Bird Flu to Humans? Fatality Rates by Strain

When assessing how deadly bird flu is to humans, data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide critical insights. As of late 2024, the overall case fatality rate (CFR) for H5N1 in humans stands at approximately 52%. This means more than half of confirmed cases have resulted in death—a stark contrast to seasonal flu, which has a CFR well below 0.1%.

However, this figure must be interpreted carefully. Because mild or asymptomatic cases may go undetected, the actual number of infections could be higher, potentially lowering the true fatality rate. Still, among symptomatic individuals, H5N1 typically causes rapid progression to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure.

H7N9 presents a similar picture. Between 2013 and 2019, over 1,600 human cases were reported, mostly in China, with a CFR around 40%. Although no human cases were confirmed after 2019 due to improved biosecurity measures, the potential for re-emergence remains.

More recently, clade 2.3.4.4b of H5N1 has been spreading globally among wild birds and poultry since 2020. In 2022, the United States reported its first human case linked to this strain, involving a person exposed to backyard poultry in Colorado. The individual experienced mild symptoms and recovered fully—highlighting that not all exposures lead to severe disease.

| Strain | First Detected | Human Cases (Global) | Fatality Rate | Recent Activity (2023–2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1996 | ~900 | ~52% | Widespread in birds; sporadic human cases |

| H7N9 | 2013 | ~1,600 | ~40% | No recent human cases |

| H9N2 | 1968 | Dozens | Low | Ongoing low-level transmission |

| H5N6 | 2014 | ~100 | ~60% | Occasional human cases in Asia |

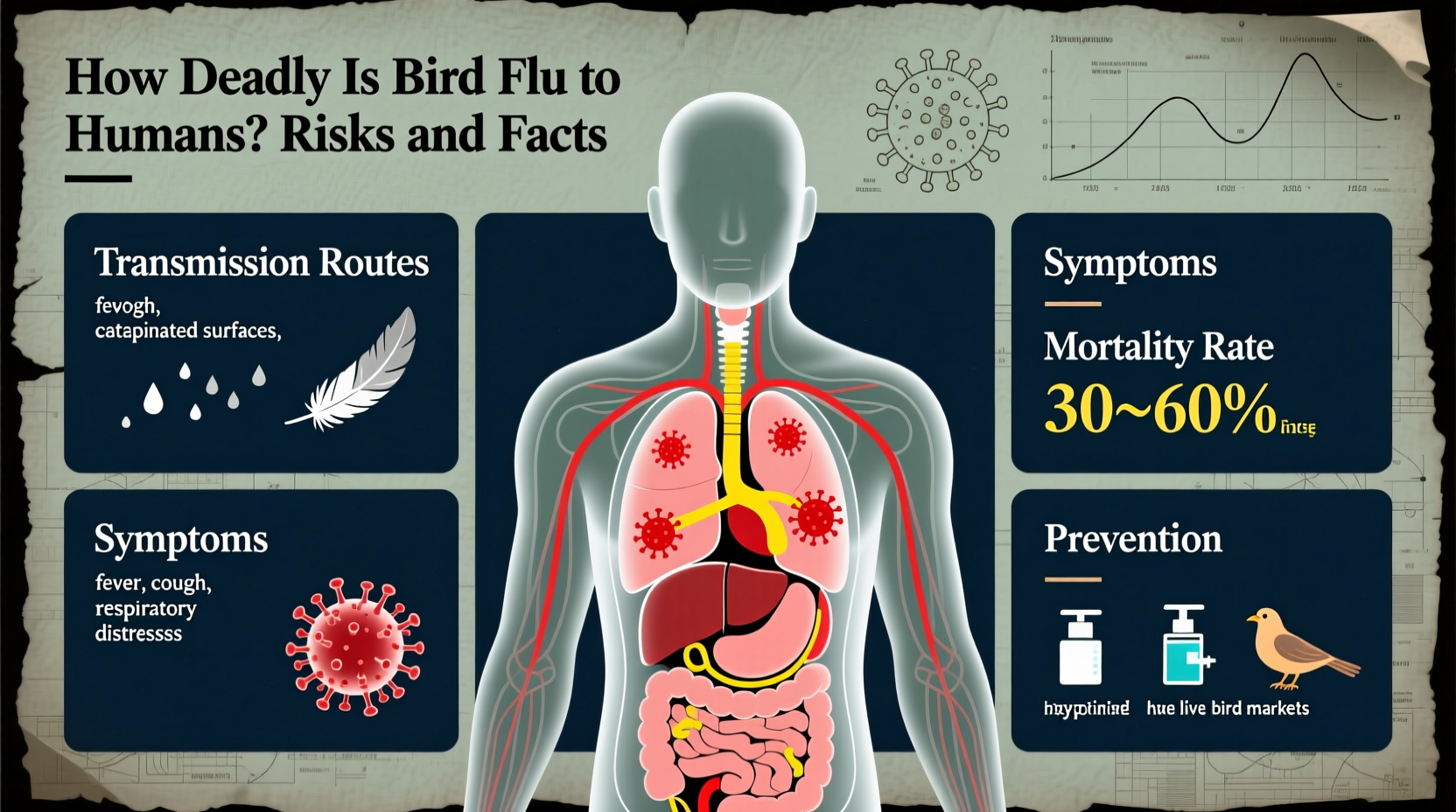

Transmission: How Do Humans Get Infected?

One of the key reasons bird flu isn’t more deadly on a population level is that it does not spread easily between humans. Most human infections result from direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments—such as live poultry markets, farms, or surfaces exposed to bird droppings.

The virus enters the body through the eyes, nose, or mouth. People involved in poultry handling, culling operations, or veterinary work face the highest risk. There is no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission, though limited, non-sequential cases have occurred in close family clusters—possibly due to shared exposure or rare genetic susceptibility.

A major concern among scientists is viral mutation. If H5N1 or another strain acquires the ability to transmit efficiently between people while retaining high virulence, it could trigger a pandemic. So far, such adaptation has not occurred, but ongoing monitoring is essential.

Symptoms and Medical Response

Symptoms of bird flu in humans usually appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure. Early signs resemble seasonal influenza: fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches. However, the disease can progress rapidly to severe lower respiratory tract illness, including pneumonia and ARDS.

Other possible symptoms include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and neurological changes. Laboratory testing—such as RT-PCR or viral sequencing—is required for confirmation, as clinical presentation alone cannot distinguish bird flu from other respiratory infections.

Treatment involves antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), or peramivir, ideally administered within 48 hours of symptom onset. Corticosteroids and supportive care in intensive care units are often needed for severe cases. Vaccines for seasonal flu do not protect against avian strains.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis with antivirals may be recommended for high-risk workers during outbreaks. Additionally, investigational H5N1 vaccines have been developed and stockpiled by some governments for emergency use, though they are not widely available to the public.

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—as messengers, omens, or spiritual beings. In many traditions, birds represent freedom, transcendence, and connection between earth and sky. Yet, outbreaks of diseases like bird flu challenge these positive associations, casting birds as carriers of invisible threats.

In parts of Asia, where live bird markets are culturally embedded, efforts to control avian flu have sparked tension between public health mandates and traditional practices. Culling millions of chickens to contain outbreaks disrupts livelihoods and raises ethical concerns about animal welfare and food security.

Conversely, Western responses often emphasize containment and scientific management. Migratory birds, once celebrated for their natural wonder, are now monitored as potential vectors of disease. Satellite tracking and genomic surveillance help predict spread, blending ecological reverence with epidemiological caution.

This duality reflects broader societal attitudes: we admire birds even as we fear what they might carry. Public education plays a vital role in balancing respect for nature with prudent health measures.

Current Global Status and Outbreak Trends (2023–2024)

As of early 2024, H5N1 continues to circulate widely in wild bird populations across Europe, North America, and Africa. Unusual mortality events in seabird colonies—such as gannets, puffins, and albatrosses—have drawn attention to the ecological impact. In the U.S., over 50 million commercial and backyard birds have been affected since 2022, leading to egg shortages and economic losses.

Human cases remain rare. In 2023, Cambodia reported two fatal H5N1 infections—one in a young girl who had contact with sick ducks. The incident prompted renewed calls for community-based surveillance and education in rural areas.

The UK recorded a single non-fatal case in 2022 in a person linked to an infected poultry farm. No secondary transmission was detected. Similarly, in 2024, Spain identified one case in a worker at a mink farm where H5N1 jumped from birds to mammals—an alarming development suggesting expanded host range.

These isolated incidents underscore that while the immediate risk to the general public remains low, vigilance is crucial. International cooperation through organizations like WHO, FAO, and OIE helps coordinate response strategies and share data in near real time.

Practical Advice for Travelers and Bird Enthusiasts

For those concerned about how deadly bird flu is to humans during travel or outdoor activities, several precautions reduce risk:

- Avoid visiting live bird markets or poultry farms in regions experiencing outbreaks.

- Do not touch sick or dead birds; report them to local wildlife authorities.

- Wash hands thoroughly after any outdoor activity involving birds or natural habitats.

- Use gloves and masks if handling birds (e.g., banding, rehabilitation).

- Ensure poultry and eggs are fully cooked before consumption.

Birdwatchers should maintain distance from flocks, especially if birds appear lethargic or disoriented. Binoculars and spotting scopes allow safe observation. Joining citizen science programs like eBird or iNaturalist can contribute valuable data without increasing personal risk.

Travelers to countries with active outbreaks should consult national health advisories—such as those from the CDC or European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)—before departure. Some destinations may impose temporary restrictions on bird-related tourism or agricultural visits.

Debunking Common Misconceptions

Several myths persist about bird flu and its danger to humans:

Misconception 1: Eating chicken or eggs spreads bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. The risk lies in handling raw products from infected animals, not consumption.

Misconception 2: All bird flu strains are equally dangerous.

Fact: Low-pathogenic strains cause mild illness in birds and rarely infect humans. Only specific subtypes pose significant threats.

Misconception 3: The virus spreads easily through the air like COVID-19.

Fact: Current strains require close contact with infected birds or environments. Airborne transmission between humans has not been established.

Misconception 4: A vaccine exists for everyone.

Fact: Seasonal flu shots don’t protect against avian flu. Experimental vaccines are reserved for emergencies and high-risk groups.

Future Outlook and Preparedness

The question of how deadly bird flu is to humans hinges on multiple evolving factors: viral evolution, environmental change, agricultural practices, and global health infrastructure. Climate change may alter bird migration patterns, increasing overlap between wild and domestic species. Intensive farming creates conditions conducive to rapid viral spread.

To prepare, countries must invest in early warning systems, laboratory capacity, and transparent reporting. One Health initiatives—integrating human, animal, and environmental health—are increasingly adopted to address zoonotic risks holistically.

Research into universal influenza vaccines and faster diagnostic tools offers hope for reducing future impacts. Meanwhile, public awareness remains a frontline defense. By understanding both the real risks and limitations of current knowledge, individuals and institutions can respond wisely to emerging threats.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you get bird flu from eating chicken?

No, you cannot get bird flu from eating properly cooked chicken or eggs. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F).

How many human deaths have been caused by bird flu?

Since 2003, the WHO has recorded over 460 deaths from H5N1 out of about 900 confirmed cases. Exact numbers vary slightly by source.

Is there a bird flu vaccine for humans?

There is no commercially available vaccine for the general public. Governments have stockpiled pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccines for emergency use in high-risk personnel.

Can pets get bird flu?

Cats can become infected by eating infected birds, though cases are rare. Dogs appear less susceptible. Keep pets away from sick or dead birds.

Should I stop birdwatching due to bird flu?

No, but practice caution: avoid close contact with birds, do not handle dead animals, and wash hands after outings. The risk to observers is extremely low.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4