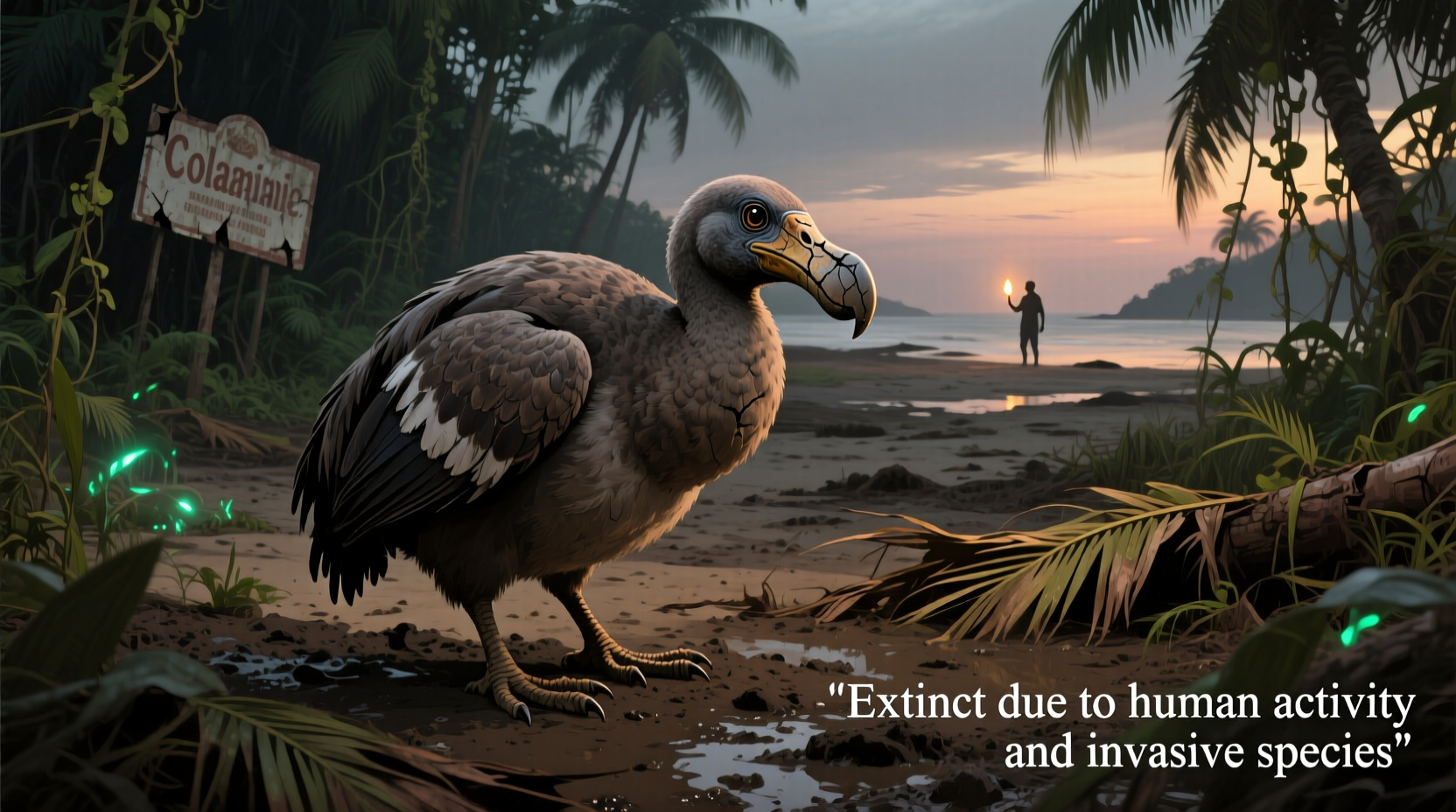

The dodo bird went extinct primarily due to human activity following its discovery on the island of Mauritius in the late 16th century. How did the dodo bird go extinct? The answer lies in a combination of habitat destruction, hunting, and the introduction of invasive species such as rats, pigs, and monkeys that preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food. This flightless bird, endemic to a single island with no natural predators prior to human arrival, was ill-equipped to survive these sudden ecological disruptions. The last widely accepted sighting of a live dodo was in 1662, marking one of the first well-documented cases of human-driven extinction.

Historical Background: Discovery and Early Encounters

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was first encountered by humans in 1598 when Dutch sailors landed on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Isolated from mainland ecosystems for millions of years, the dodo had evolved without fear of predators. It was a large, flightless pigeon-like bird, weighing around 10â18 kilograms (22â40 pounds), with a prominent hooked beak and short, stout legs. Its lack of flight and apparent fearlessness made it easy prey for seafarers who used it as a source of fresh meat during long voyages.

Early accounts from sailors described the dodo as clumsy and unpalatable, yet its abundance and ease of capture led to widespread killing. These initial interactions set the stage for rapid population decline. Unlike migratory birds or those living across broad geographic ranges, the dodo existed only on Mauritius, making it extremely vulnerable to environmental changes. Any threat to its limited habitat could spell disaster for the entire species.

Primary Causes of Extinction

Understanding how the dodo bird went extinct requires examining several interrelated factors:

- Habitat Destruction: As settlers established colonies on Mauritius, they cleared forests for agriculture and construction. The dodoâs nesting grounds and food sourcesâprimarily fruits and seeds from native treesâwere destroyed or altered.

- Hunting by Humans: Although not considered a delicacy, the dodo was hunted for food by sailors and colonists. Even if individual consumption was low, repeated exploitation over decades contributed to population loss. \li>Invasive Species: Perhaps the most devastating factor was the introduction of non-native animals. Rats, pigs, dogs, and crab-eating macaques arrived with ships and quickly spread across the island. These animals raided dodo nests, eating eggs and chicks. Since the dodo nested on the ground and laid only one egg at a time, reproductive success plummeted.

- Lack of Evolutionary Adaptation: Having evolved in isolation without predators, the dodo did not develop defensive behaviors or physical traits necessary for survival in a predatory environment. This evolutionary naivety left it defenseless against new threats.

These combined pressures created what ecologists call an âextinction vortexââa downward spiral from which recovery is impossible. Once the population dropped below a critical threshold, genetic diversity decreased, increasing vulnerability to disease and reducing reproductive viability.

Timeline of Decline and Final Sightings

The timeline of the dodo's extinction illustrates just how rapidly human actions can drive a species to disappearance. After its discovery in 1598, sightings were common throughout the early 1600s. However, records become sparse after 1638. The last confirmed sighting of a live dodo is generally accepted to have occurred in 1662, documented by shipwreck survivors who reported seeing the bird on an islet near Mauritius.

By the end of the 17th century, the dodo was gone. Remarkably, this means the species likely vanished within less than 70 years of sustained human contactâa blink of an eye in evolutionary terms. For many years, there was debate about whether the dodo truly existed or was a myth, partly because no complete specimens survived. Most knowledge came from sketches, written descriptions, and fragmented remains.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1598 | Dutch sailors discover the dodo on Mauritius |

| 1601â1638 | Frequent sightings and hunting by sailors and settlers |

| 1638 | Last reliable observation on mainland Mauritius |

| 1662 | Last confirmed sighting on an offshore islet |

| 1681 | Naturalist extinctions begin being recorded; dodo already presumed extinct |

Scientific Rediscovery and Fossil Evidence

It wasn't until the 19th century that scientists began reconstructing the dodoâs biology through subfossil remains found in swampy areas of Mauritius, particularly in the Mare aux Songes. Excavations revealed hundreds of bones, allowing paleontologists to piece together the birdâs anatomy and confirm its classification within the Columbidae familyâmaking it closely related to pigeons and doves.

Molecular studies in the 2000s, using DNA extracted from a preserved dodo specimen in Oxfordâs Ashmolean Museum, confirmed its closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica). This genetic insight helped reshape our understanding of island evolution and avian adaptation.

Today, the dodo serves as a cautionary tale in conservation biology. While once thought grotesque or foolish due to outdated illustrations, modern science recognizes the dodo as a highly specialized species perfectly adapted to its original environmentâuntil that environment was irrevocably changed.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

The phrase âdead as a dodoâ has entered common usage to describe something obsolete or extinct. Over time, the dodo became symbolic of human-caused extinction and ecological ignorance. Its image appears in literature, films, and environmental campaigns as a reminder of the fragility of biodiversity.

Perhaps the most famous cultural reference is in Lewis Carrollâs âAliceâs Adventures in Wonderlandâ (1865), where the Dodo character participates in the absurd âCaucus Race.â While Carroll likely chose the dodo for personal reasons (he stuttered and sometimes introduced himself as âDo-do-Dodgsonâ), the portrayal inadvertently cemented the birdâs place in popular imagination.

In contemporary times, the dodo is often invoked in discussions about climate change, deforestation, and endangered species protection. It represents both the consequences of colonial expansion and the importance of proactive conservation.

Common Misconceptions About the Dodo

Several myths persist about the dodo bird that obscure the true story of its extinction:

- Myth: The dodo was stupid. Reality: Intelligence is difficult to assess in extinct species, but the dodoâs behavior was typical of island birds with no predators. Its lack of fear was not stupidity but evolutionary adaptation.

- Myth: It went extinct because it couldnât fly. Reality: Flightlessness is common among island birds (e.g., kiwis, kakapos). The real issue was the sudden appearance of predators and habitat loss, not the inability to fly.

- Myth: We have complete dodo specimens. Reality: No fully intact soft-tissue specimens exist. The only known preserved parts are a dried head and foot housed at Oxford University, along with some skeletal fragments elsewhere.

- Myth: It took centuries to go extinct. Reality: The process was alarmingly fastâlikely under 70 years of direct human impact.

Lessons for Modern Conservation

The extinction of the dodo offers vital lessons for todayâs wildlife preservation efforts. First, isolated island ecosystems are particularly fragile. Species that evolve without predation pressure often lack survival mechanisms when new threats emerge. Second, invasive species remain one of the leading causes of extinction worldwide. Third, public awareness and scientific documentation play crucial roles in preventing future losses.

Modern technologies like GPS tracking, drone monitoring, and biosecurity protocols help protect vulnerable species. Countries with island nationsâsuch as New Zealand, Seychelles, and Hawaiiâare implementing aggressive predator control programs to prevent repeats of the dodoâs fate.

Moreover, de-extinction researchâusing genetic engineering to revive lost speciesâis exploring the possibility of bringing back the dodo. While still speculative, projects like Colossal Biosciencesâ work on the woolly mammoth suggest that similar techniques might one day apply to birds. However, ethical and ecological questions remain: even if we could resurrect the dodo, would there be a safe habitat for it to thrive?

How to Learn More and Support Bird Conservation

If you're interested in learning more about extinct birds or supporting current conservation initiatives, consider the following steps:

- Visit natural history museums that display dodo reconstructions or related exhibits.

- Support organizations like BirdLife International, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

- Participate in citizen science projects such as eBird or iNaturalist to contribute data on local bird populations.

- Educate others about the dangers of introducing non-native species into delicate ecosystems.

- Advocate for stronger environmental protections and funding for habitat restoration.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When did the dodo bird go extinct?

- The dodo bird is believed to have gone extinct around 1662, with the last confirmed sighting occurring that year. By the late 17th century, it was officially considered extinct.

- Why couldnât the dodo survive human contact?

- The dodo lacked natural defenses against predators, nested on the ground, reproduced slowly, and depended on specific forest habitatsâall of which made it highly vulnerable to human settlement and invasive species.

- Could the dodo be brought back through cloning?

- While theoretical research exists, no viable dodo DNA has been recovered for cloning. Even if technology advances, recreating a suitable ecosystem would be a major challenge.

- Was the dodo really fat and clumsy?

- Historical depictions may have exaggerated its size. Scientists now believe the dodo was likely more agile and proportionate, with weight fluctuations depending on seasonal food availability.

- Is the dodo related to dinosaurs?

- No, but all birds are descended from theropod dinosaurs. The dodo itself evolved from flying pigeon ancestors that reached Mauritius millions of years ago.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4