Birds mate through a process known as the 'cloacal kiss,' where males and females briefly press their cloacas together to transfer spermâa method central to understanding how do bird mate in both wild and domestic settings. Unlike mammals, birds lack external genitalia; instead, both sexes possess a cloaca, a single opening used for excretion and reproduction. This brief, often swift act typically follows elaborate courtship behaviors such as singing, dancing, or nest-building displays. Mating success depends on species-specific rituals, timing with breeding seasons, and environmental conditions. Understanding how do bird mate involves exploring not only the physical mechanics but also the behavioral, biological, and ecological factors that influence avian reproduction.

The Biology of Bird Reproduction

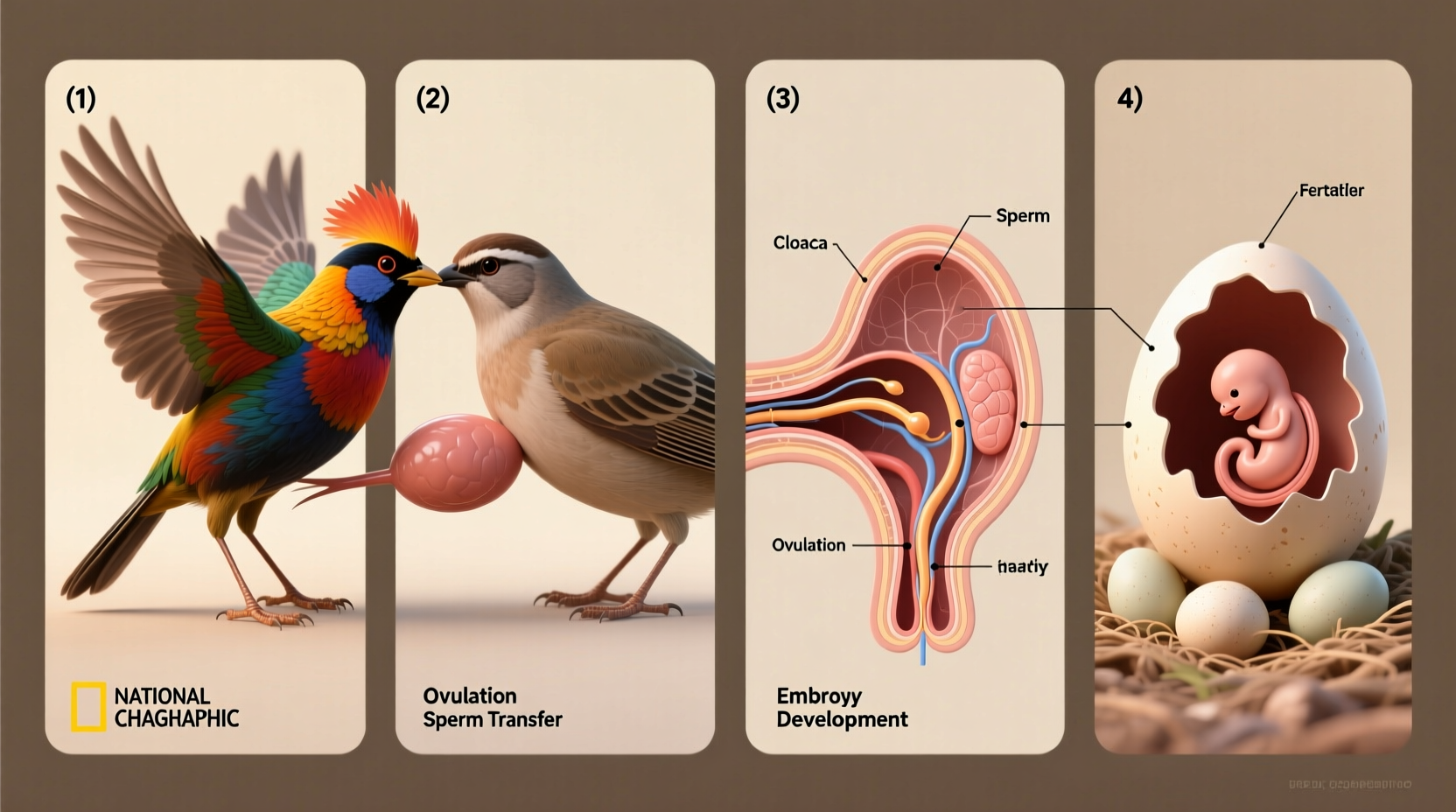

Birds are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs rather than giving birth to live young. The reproductive system differs significantly between male and female birds. In most species, males have two testes that increase in size during breeding season, producing sperm stored temporarily in the cloaca. Females usually have only one functional ovary (typically the left), which releases yolks into the oviduct where egg white, membranes, and shell are added over several days.

Sperm transfer occurs via the cloacal kissâan instantaneous touch between the maleâs and femaleâs cloacae. This may last less than a second but is sufficient for fertilization if timed correctly with ovulation. Because internal fertilization still occurs despite the lack of intromittent organs, many people wonder do birds get pregnant?âthey donât. Instead, once fertilized, the egg continues developing in the oviduct before being laid.

Courtship: The Prelude to Mating

Mating rarely happens without prior courtship. These rituals serve multiple purposes: signaling health and fitness, synchronizing reproductive readiness, and strengthening pair bonds. Examples include:

- Singing: Male songbirds like robins and nightingales use complex songs to attract mates and defend territories.

- Dancing: Cranes perform intricate dances involving leaps, bows, and wing movements. \li>Plumage Display: Peacocks fan their iridescent tail feathers, while birds-of-paradise engage in choreographed visual performances.

- Gift-Giving: Some species, like penguins, offer stones or food as nuptial gifts.

- Nest Demonstrations: Male bowerbirds build elaborate structures decorated with colorful objects to impress females.

These behaviors answer the broader question of how do birds choose their mates, revealing that selection is based on genetic quality indicators such as symmetry, coloration, stamina, and creativity.

Breeding Seasons and Timing

The timing of mating is closely tied to seasonal changes. Most temperate-zone birds breed in spring and early summer when food is abundant and temperatures are favorable for raising chicks. Photoperiodâthe length of daylightâtriggers hormonal changes that stimulate gonadal development.

Tropical species may breed year-round or align with rainy seasons, while some seabirds like albatrosses have extended cycles, mating every other year due to the long chick-rearing period. For backyard birdwatchers curious about when do birds mate, observing increased territorial behavior, nest construction, and vocalizations can signal the onset of breeding.

Pairs and Mating Systems

Birds exhibit diverse mating systems, influencing how and how often they mate:

| Mating System | Description | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Monogamy | One male pairs with one female for at least one breeding season | Swans, eagles, many songbirds |

| Serial Monogamy | Pair bonds last one season but change partners annually | Robins, sparrows |

| Polygyny | One male mates with multiple females | Red-winged blackbirds, grouse |

| Polyandry | One female mates with multiple males | Jacanas, spotted sandpipers |

| Promiscuity | Both sexes mate with multiple partners | Ruffs, lekking birds |

Monogamy dominates among birds, especially in species requiring biparental care. However, genetic studies show that social monogamy doesn't always equal sexual fidelityâextra-pair copulations are common even in seemingly devoted pairs.

Physical Mechanics of Copulation

Once courtship succeeds, actual copulation begins with the male mounting the female from behind. She often leans forward or crouches, lifting her tail to expose the cloaca. The male balances on her back, arches his body, and everts his cloaca to make contact. Though it appears abrupt, this moment is highly coordinated.

Some waterfowl, like ducks and geese, are exceptionsâthey possess a phallus that allows for internal insemination, sometimes forcibly. This has led to evolutionary arms races, with females evolving convoluted vaginal tracts to limit unwanted fertilization. This unique adaptation raises ethical questions in wildlife biology and underscores the complexity behind how do bird mate across different families.

Frequency of Mating

Copulation frequency varies widely. Many birds mate multiple times per day during peak fertility. For instance, chickens may mate dozens of times weekly in flock settings. Frequent mating increases the likelihood of successful fertilization and reinforces pair bonds. In migratory species, mating may occur shortly after arrival at breeding grounds to maximize reproductive output within limited windows.

Egg Laying and Incubation

After mating, fertilization occurs in the upper oviduct. The full egg takes 24â48 hours to form before laying. Clutch size ranges from one (e.g., albatross) to over a dozen (e.g., quail), depending on species and environment.

Incubation periods vary: small songbirds hatch in 10â14 days, while larger birds like eagles may take up to 35 days. Both parents may share duties, or one sex may assume primary responsibility. For example, male emperor penguins incubate eggs through Antarctic winters, fasting for months.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Mating

Several myths persist about avian reproduction:

- Misconception: Birds mate like mammals with prolonged intercourse.

Truth: Most copulations last seconds and involve cloacal contact only. - Misconception: All birds form lifelong pairs.

Truth: While swans and albatrosses often stay together for life, many species re-pair annually. - Misconception: Female birds need a male present to lay eggs.

Truth: Hens will lay unfertilized eggs without a roosterâcommon in poultry farms. - Misconception: Baby birds imprint on the first moving object they see.

Truth: Imprinting applies mainly to precocial species like ducks; altricial nestlings rely more on auditory cues.

Observing Bird Mating: Tips for Birdwatchers

If you're interested in witnessing mating behaviors firsthand, consider these practical tips:

- Visit During Breeding Season: Plan outings between March and July in North America, earlier in southern regions.

- Arrive Early: Birds are most active at dawn when singing and courtship peak.

- Use Binoculars or a Telephoto Lens: Avoid disturbing animals by maintaining distance.

- Listen for Calls: Aggressive chirping or duetting may indicate mating activity.

- Look for Nesting Signs: Carrying twigs, inspecting cavities, or defensive behavior suggest nestingâand recent matingâis underway.

- Respect Wildlife: Never approach nests too closely; stress can cause abandonment.

Human Impact on Avian Mating Success

Urbanization, climate change, and light pollution affect bird mating patterns. Artificial lighting can disrupt circadian rhythms, altering singing schedules and reducing mating opportunities. Habitat fragmentation limits access to mates and nesting sites. Pesticides can impair fertility or reduce insect availability crucial for feeding young.

On a positive note, conservation efforts like nest box programs help cavity-nesting species thrive in developed areas. Citizen science projects such as NestWatch allow public participation in monitoring breeding success, contributing valuable data to ornithologists studying how do bird mate under changing conditions.

Regional Differences in Mating Behavior

Mating strategies differ across continents and ecosystems. Arctic-nesting shorebirds experience continuous daylight, enabling near-constant courtship displays. In contrast, dense rainforest environments favor acoustic signals over visual ones due to limited visibility.

In urban areas, some birds adjust their songs to higher pitches to overcome low-frequency traffic noise, potentially affecting mate attraction. European blackbirds in cities may start breeding earlier than rural counterparts due to warmer microclimates and extended food availability.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How long does bird mating take?

- The actual cloacal kiss lasts less than a second, though courtship may span minutes to hours.

- Do all birds lay eggs after mating?

- Yes, all birds reproduce by laying eggs, but females may not lay immediately and some lay infertile eggs without mating.

- Can birds mate in flight?

- No confirmed cases exist. Mating requires physical stability, so it occurs on branches, ground, or water surfaces.

- How can I tell if birds are mating or fighting?

- Mating involves the male mounting gently from behind with tail alignment. Fighting includes chasing, pecking, and wing-slapping.

- Do pet birds need to mate to be happy?

- No. While social interaction is important, pet birds donât require mating for emotional well-being. Providing enrichment and companionship suffices.

Understanding how do bird mate reveals the remarkable diversity and adaptability of avian life. From microscopic sperm transfer to continent-spanning migrations timed with reproductive needs, bird mating is a finely tuned interplay of biology, behavior, and environment. Whether youâre a researcher, conservationist, or casual observer, appreciating these processes deepens our connection to the natural world and informs better stewardship of bird populations worldwide.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4