Birds don't get electrocuted on power lines because they typically touch only one wire at a time, preventing electrical current from flowing through their bodies—a principle known as not completing the circuit. This is why you'll often see multiple birds perched safely on high-voltage transmission lines without harm. A common variation of the query 'how do birds not get electrocuted' is 'why don't birds get shocked on power lines,' and the answer lies in basic principles of electricity and avian behavior. As long as the bird remains isolated from the ground or another conductor with a different voltage, no significant current passes through it, making the perch perfectly safe—under normal conditions.

The Science Behind Electrical Circuits and Bird Safety

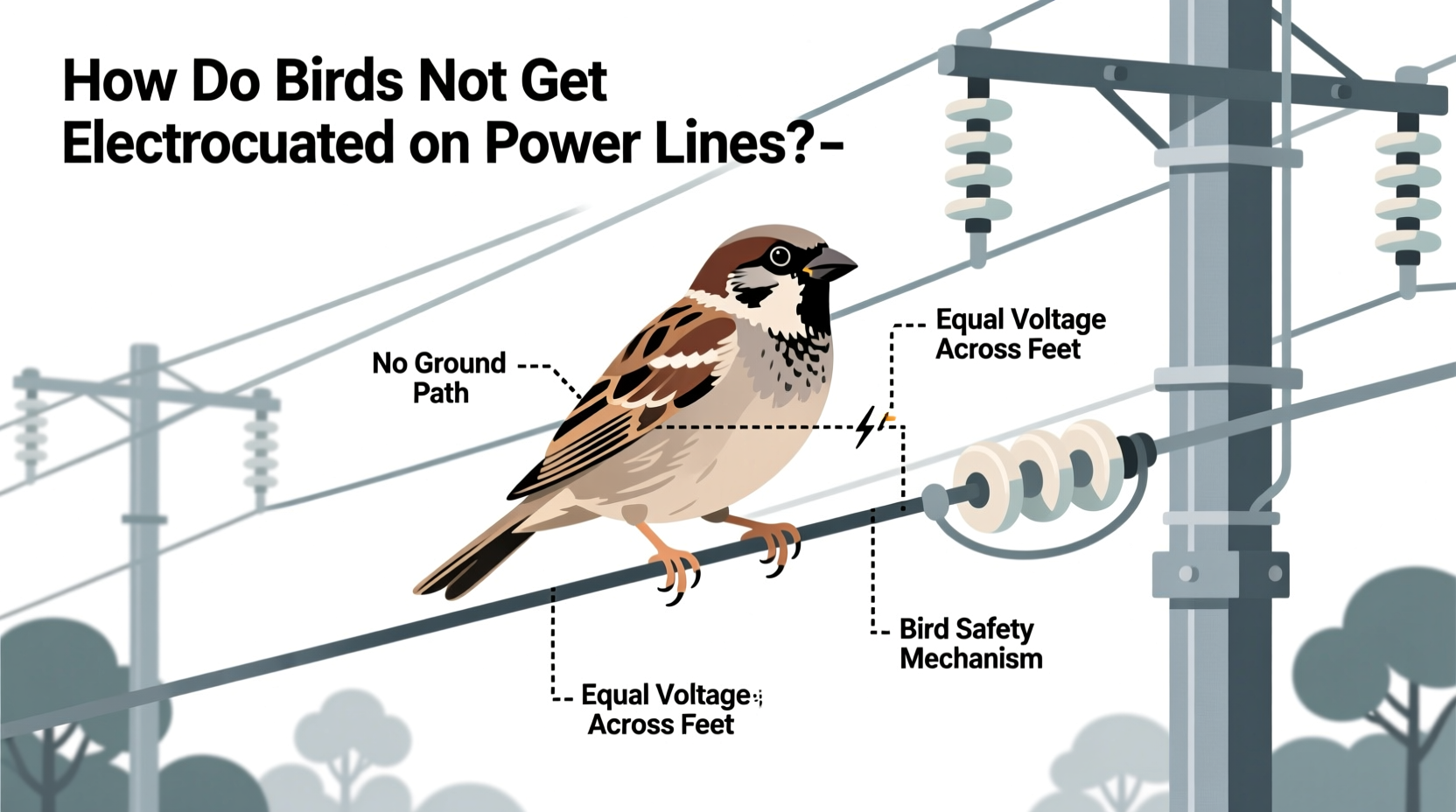

To understand why birds aren’t electrocuted, it's essential to grasp how electricity flows. Electric current moves from a point of higher voltage to lower voltage along a conductive path. For a shock to occur, there must be a complete circuit—meaning electricity enters the body at one point and exits at another, usually toward the ground or another wire.

When a bird lands on a single power line, both of its feet are at approximately the same electrical potential. Since there’s no voltage difference across its body, current doesn't flow through it. The bird essentially becomes part of the circuit's path without interrupting or diverting the flow. This phenomenon answers variations like 'can birds get electrocuted on power lines' and 'what happens if a bird touches two wires.'

However, danger arises when a bird simultaneously contacts two wires with different voltages or one wire and a grounded structure (like a utility pole). In such cases, the bird completes a circuit, allowing current to pass through its body—which can result in electrocution. Large birds such as eagles, hawks, and owls are especially vulnerable due to their wide wingspans, which increase the likelihood of bridging gaps between conductors.

Biological Adaptations That Help Birds Stay Safe

While physics plays the primary role, some biological traits also contribute to birds’ safety. Most birds have dry, scaly legs made of keratin—a poor conductor of electricity. This natural insulation further reduces the chance of current entering their bodies even if minor voltage differences exist.

Additionally, birds lack sweat glands on their feet, minimizing moisture that could enhance conductivity. Their instinctive behaviors—such as avoiding contact with multiple surfaces while perching—also reduce risk. These adaptations don’t make them immune, but they support survival in environments filled with electrical infrastructure.

When Do Birds Get Electrocuted? High-Risk Scenarios

Despite their usual safety, birds—especially raptors—are frequently victims of electrocution worldwide. According to studies by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, thousands of birds die annually from power line-related incidents, particularly in rural and open landscapes where poles serve as the tallest structures.

- Touching Two Wires Simultaneously: If a large bird stretches its wings and contacts two energized wires with differing voltages, current flows through its body, causing fatal electrocution.

- Contact with Grounded Structures: When a bird on a live wire touches a metal transformer, pole, or guy wire connected to the ground, it creates a path for electricity to discharge.

- Damaged or Poorly Designed Infrastructure: Older power poles may have inadequate spacing between components, increasing the risk for larger species.

- Nesting Behavior: Some birds build nests on utility poles using conductive materials like wire or wet twigs, raising the risk of short circuits or personal injury.

Species most affected include golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, great horned owls, and sandhill cranes. Conservationists and utility companies have responded with mitigation strategies to protect these animals.

Utility Design and Avian Protection Measures

Recognizing the ecological impact, many electric utilities now implement avian-safe design standards. These include:

- Increasing spacing between conductors to prevent wing-span bridging

- Insulating exposed wires and connections

- Installing perch deterrents or elevated roosting platforms away from hazardous zones

- Using covered or shielded cable in high-risk areas

- Relocating poles or lines from critical habitats

Organizations like the Avian Power Line Interaction Committee (APLIC) provide guidelines for reducing bird fatalities. For example, recommended minimum phase-to-phase spacing for raptor protection ranges from 48 to 96 inches depending on species and region. Utilities in states like California, Wyoming, and Montana have adopted these practices to comply with environmental regulations and conservation agreements.

| Risk Factor | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Short Conductor Spacing | Wires too close together allow large birds to bridge gap | Increase separation or insulate lines |

| Grounded Metal Components | Poles or transformers create paths to earth | Install insulation caps or barriers |

| Lack of Perch Space | Birds forced onto dangerous parts of pole | Add safe perching devices above hazard zone |

| Old Infrastructure | Legacy systems not designed with wildlife in mind | Upgrade during routine maintenance |

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Birds on Wires

Beyond biology and engineering, birds lined up on power lines have captured human imagination. They’re often seen as symbols of unity, communication, or fleeting moments of stillness amid modern chaos. Photographers and filmmakers use this image to evoke themes of migration, freedom, or urban-nature coexistence.

In literature and art, flocks on wires sometimes represent conformity or collective behavior. Yet paradoxically, each bird maintains its own space—much like individuals in society. While unrelated to the technical question of 'how do birds not get electrocuted,' these cultural layers enrich our appreciation of everyday avian scenes.

Practical Tips for Observing Birds Around Power Lines

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, power lines can be excellent vantage points for spotting certain species. Here’s how to observe responsibly and safely:

- Use Binoculars: Maintain a respectful distance; never approach poles or substations.

- Identify Species: Look for field marks such as size, plumage, tail shape, and posture. Swallows, starlings, blackbirds, and grackles commonly gather on wires.

- Note Behavior: Watch for takeoff patterns, feeding flights, or interactions—these can reveal social hierarchies or territorial disputes.

- Avoid Disturbance: Loud noises or sudden movements may scare birds unnecessarily.

- Report Injured Birds: If you see a bird entangled or injured near electrical equipment, contact local wildlife rehabilitators or utility providers immediately.

Remember: never attempt to rescue a bird from a power line yourself. Only trained professionals should handle such situations due to electrocution risks.

Regional Differences in Bird-Electrical Interactions

The frequency of bird electrocutions varies globally based on infrastructure design, climate, and local fauna. In arid regions like the southwestern United States or parts of Spain, raptors frequently use power poles as hunting lookouts due to sparse natural perches. This increases collision and electrocution rates.

In contrast, countries like Germany and the Netherlands have stricter regulations requiring insulated cabling and underground transmission in ecologically sensitive zones. Urban areas tend to have fewer incidents due to more diverse perch options and better-maintained systems.

In developing nations, aging grids and limited funding for upgrades often lead to higher avian mortality. International conservation groups work with governments to retrofit dangerous poles and train utility workers in bird-safe practices.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Electricity

Several myths persist about birds and power lines. Addressing these helps clarify public understanding:

- Myth: Birds are insulated by their feathers.

Truth: Feathers offer minimal protection against high voltage. Safety comes from not completing a circuit. - Myth: All birds are immune to electric shocks.

Truth: Any bird can be electrocuted if it bridges two potentials. - Myth: Insulated wires eliminate risk.

Truth: Many 'insulated' lines are only coated for weather resistance, not full dielectric protection. - Myth: Small birds are safer than large ones.

Truth: Size matters less than behavior and environment—though larger wingspans increase risk.

What You Can Do to Help Protect Birds

Individuals and communities play a role in reducing avian electrocutions:

- Support legislation promoting bird-safe infrastructure.

- Report dangerous utility setups to your local provider or conservation agency.

- Participate in citizen science projects tracking bird collisions or nesting activity near power lines.

- Educate others about the real reasons birds don’t get shocked—and when they might.

Utilities increasingly welcome collaboration. Some offer programs allowing residents to request avian safety audits in their neighborhoods.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why don’t birds get shocked on power lines?

- Birds don’t get shocked because they touch only one wire, so electricity doesn’t flow through their bodies. Without a voltage difference, there’s no current.

- Can birds sit on power lines without getting electrocuted?

- Yes, as long as they don’t touch another wire or a grounded object, birds can sit safely on a single power line.

- Why are large birds more at risk of electrocution?

- Larger birds, like eagles and hawks, have wide wingspans that can accidentally bridge two wires or connect a wire to a pole, creating a deadly circuit.

- Do rubber coatings on wires protect birds?

- Not always. Many coatings are for weather protection, not insulation. True dielectric covers are needed to prevent electrocution.

- What should I do if I see an electrocuted bird?

- Contact your local wildlife authority or utility company. Do not touch the bird or equipment—it may still be energized.

Understanding how birds avoid electrocution combines physics, biology, and environmental awareness. While they’re naturally protected under simple perching conditions, human-designed hazards remain a threat—especially to vulnerable species. By improving infrastructure and spreading knowledge, we can ensure that power lines remain places of rest, not danger, for our feathered neighbors.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4