Birds reproduce through internal fertilization, followed by egg-laying and incubationâa process that defines avian reproduction across thousands of species worldwide. The question how do birds reproduce is best answered by understanding their unique reproductive biology and behaviors, which differ significantly from mammals. Unlike live-bearing animals, nearly all bird species are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs that develop and hatch outside the motherâs body. This reproductive strategy involves courtship rituals, mating, formation of a fertilized egg, nesting, and dedicated parental care during incubation and chick-rearing stages.

The Biological Basis of Bird Reproduction

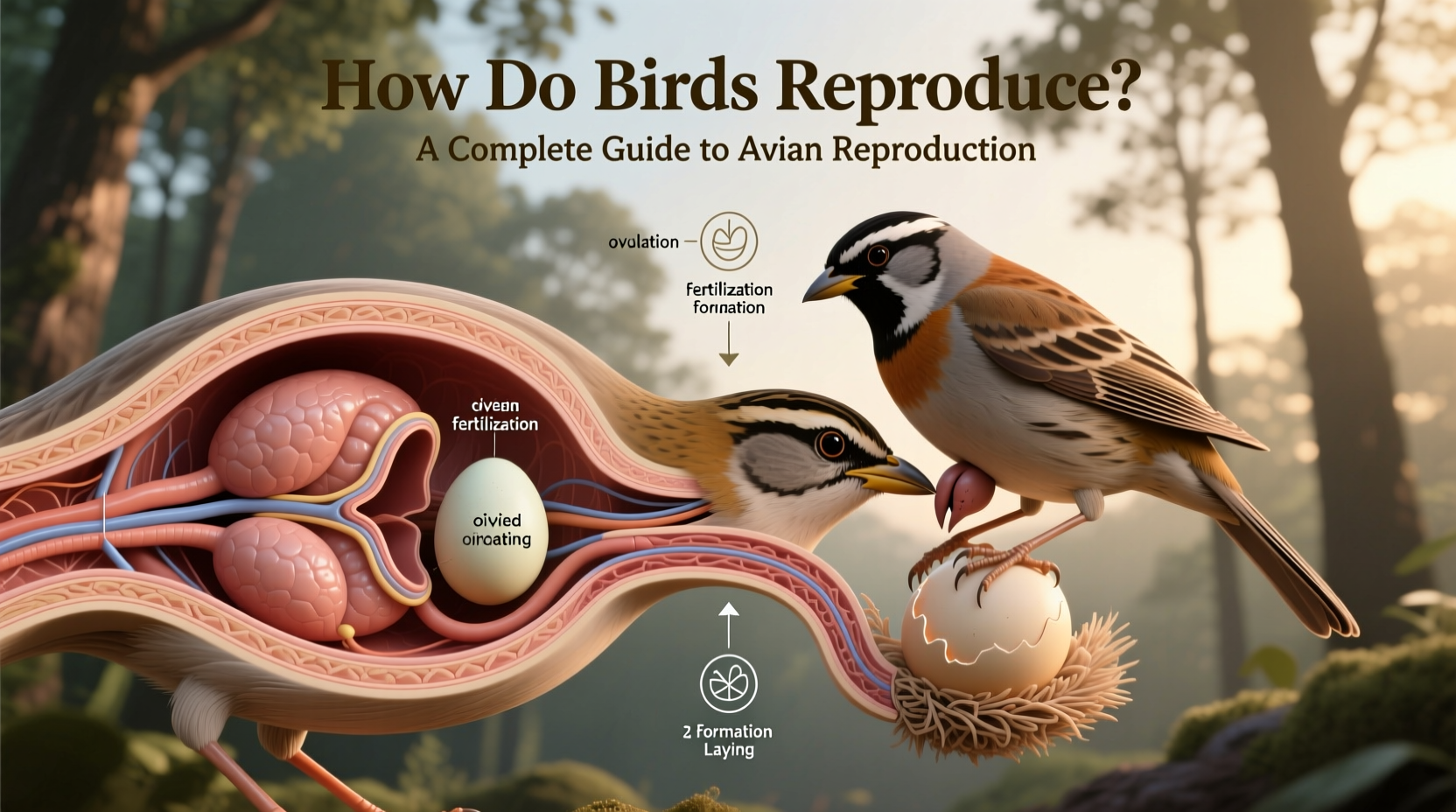

Birds have a specialized reproductive system adapted for flight and efficient energy use. Both males and females typically possess only one functional gonadâfemales usually have a single ovary (on the left side), and males have two testes located internally near the kidneys. During breeding season, these organs swell and produce gametes: sperm in males and ova (egg cells) in females.

Mating in birds occurs through a brief contact known as the 'cloacal kiss,' where the male transfers sperm from his cloacaâthe single posterior opening used for excretion and reproductionâto the femaleâs cloaca. There is no external penis in most bird species (with notable exceptions like ducks, geese, and some ratites such as ostriches). Fertilization happens internally when sperm travel up the oviduct and meet the mature ovum.

After fertilization, the egg begins forming in the femaleâs oviduct. Over approximately 24 hours, layers are added: first the albumen (egg white), then shell membranes, and finally the calcium carbonate shell. Pigments may be deposited depending on the species, giving eggs their distinctive colors and patterns. Once fully formed, the egg is laidâusually within a nest specifically prepared for this purpose.

Courtship and Mating Behavior

Before reproduction can occur, birds must attract a mate. Courtship displays vary widely among species and often involve elaborate visual, auditory, and behavioral elements. These rituals answer the deeper question behind how do birds reproduce sexually, emphasizing not just physiology but also social dynamics.

Examples include:

- Songbirds: Males sing complex songs to establish territory and attract females.

- Peafowl: Males fan their iridescent tail feathers in dramatic displays.

- Albatrosses: Perform synchronized dances involving bowing, bill clapping, and sky-pointing.

- Bowerbirds: Build intricate structures decorated with colorful objects to impress mates.

These behaviors serve dual purposes: ensuring genetic compatibility and demonstrating fitness. In many species, monogamy prevails during a breeding season, though some engage in polygyny or polyandry. Long-term pair bonds, especially in raptors and seabirds, enhance reproductive success through coordinated parenting.

Egg Formation and Laying Patterns

The timing and frequency of egg-laying depend on species, environment, and food availability. Most birds lay one egg per day until the clutch is complete. Clutch size ranges from one (e.g., albatrosses) to over a dozen (e.g., bobwhite quail).

Key factors influencing egg production include:

- Photoperiod: Increasing daylight triggers hormonal changes that stimulate ovulation.

- Nutrition: Adequate calcium and protein intake are essential for strong shells and yolk development.

- Age and health: Younger or stressed birds may lay fewer or misshapen eggs.

Eggs themselves are marvels of evolutionary engineering. Their asymmetrical shape helps them roll in a tight circle, reducing the risk of falling from nests. The porous shell allows gas exchange while protecting against dehydration and microbial invasion. Yolk provides nutrients; albumen cushions the embryo and supplies water and protein.

Incubation: Keeping Eggs Viable

Once laid, eggs require consistent warmth to develop properly. Incubation periods vary greatlyâfrom 10 days in small songbirds like finches to over 80 days in large albatrosses.

Parental roles in incubation differ across species:

- In many passerines, both parents share duties.

- In some raptors, the female primarily incubates while the male hunts. \li>In emperor penguins, males balance eggs on their feet under a brood pouch for months in Antarctic winter.

Temperature regulation is critical. Deviations of just a few degrees can halt development or cause deformities. Parents rotate eggs regularly to ensure even heating and prevent embryonic adhesion to the shell lining.

| Bird Species | Avg. Incubation Period | Clutch Size | Primary Incubator |

|---|---|---|---|

| House Sparrow | 10â14 days | 4â6 | Female |

| Bald Eagle | 34â36 days | 1â3 | Both (female dominant) |

| Emperor Penguin | 64â67 days | 1 | Male |

| Chicken (Domestic) | 21 days | Varies | Hen |

| Atlantic Puffin | 36â45 days | 1 | Both |

Hatching and Chick Development

As the embryo matures, it uses stored nutrients and oxygen diffusing through the shell. Just before hatching, the chick uses a temporary structure called an 'egg tooth' to break through the inner membrane and then chip away at the shell in a process known as 'pipping.'

Two main types of chicks emerge:

- Altricial: Born blind, featherless, and helpless (e.g., robins, hawks, owls). They rely entirely on parents for warmth and food.

- Precocial: Hatch with open eyes, downy feathers, and the ability to walk or swim shortly after birth (e.g., ducks, chickens, killdeer). They follow parents and feed themselves early but still need protection.

Growth rates are rapid. Songbird chicks may double in size daily during the first week. Feeding frequency can exceed 100 times per day in some species, highlighting the intense parental investment required.

Migration and Breeding Seasons

Understanding how do birds reproduce in the wild requires considering seasonal cycles. Most temperate-zone birds breed in spring and summer when food is abundant. Tropical species may breed year-round or align with rainy seasons.

Migratory birds face additional challenges. They must time their arrival at breeding grounds precisely to coincide with peak insect emergence or plant productivity. Climate change is disrupting these synchronizations, affecting reproductive success.

Some species exhibit delayed implantation or facultative parthenogenesis (rarely), but these are exceptions rather than norms in avian biology.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Reproduction

Several myths persist about how birds reproduce. Addressing them clarifies public understanding:

- Myth: All birds sit on their eggs immediately after laying.

Truth: Many begin incubation only after the last egg is laid to ensure synchronous hatching. - Myth: If you touch a baby bird, the parents will reject it.

Truth: Most birds have a poor sense of smell; they wonât abandon chicks due to human scent. However, unnecessary handling should be avoided to minimize stress. - Myth: Birds mate only once per season.

Truth: Many species raise multiple broods annually, especially if early attempts fail or conditions are favorable.

Observing Bird Reproduction: Tips for Birdwatchers

For those interested in witnessing avian reproduction firsthand, ethical observation is key. Here are practical tips:

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Maintain distance to avoid disturbing nesting birds.

- Visit during breeding season: In North America, this typically runs from March to August, depending on latitude and species.

- Look for nesting signs: Carrying twigs, frequent visits to a location, or defensive behavior indicate active nests.

- Avoid flash photography: Sudden light can startle adults and disorient chicks.

- Report rare sightings responsibly: Share data with citizen science platforms like eBird without disclosing exact locations publicly.

Human Impact and Conservation

Urbanization, pesticide use, and habitat loss threaten bird reproduction. Pesticides like DDT historically caused thin-shelled eggs that broke prematurely. Today, climate shifts alter migration and breeding timelines, leading to mismatches between chick hatching and food availability.

Conservation efforts focus on preserving nesting habitats, controlling invasive predators (like rats and cats), and installing artificial nest boxes for cavity-nesting species such as bluebirds and owls.

Supporting native plants, reducing light pollution, and keeping pets indoors during breeding season can all improve reproductive outcomes for local bird populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds lay eggs?

- Yes, all bird species are oviparous and reproduce by laying eggs. No bird gives birth to live young.

- How long does it take for bird eggs to hatch?

- Hatching time varies by speciesâfrom 10 days in small passerines to over two months in large seabirds like albatrosses.

- Can birds reproduce without a male?

- In rare cases, some female birds (especially in captivity) can produce unfertilized eggs or undergo facultative parthenogenesis, but viable offspring without mating are extremely uncommon.

- What should I do if I find a baby bird out of the nest?

- If it's featherless (altricial), gently return it to the nest if safe. If it has feathers and is hopping (precocial), it's likely learning to forage and its parents are nearby.

- How many times a year do birds lay eggs?

- Most birds have one to two broods per year, though some, like American Robins, may raise three or more if conditions allow.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4