Birds see the world in a way that is both more vibrant and more detailed than human vision. The question of how do birds see reveals a fascinating blend of advanced biology and evolutionary adaptation. Unlike humans, most birds have four types of cone cells in their eyes—compared to our three—allowing them to perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. This expanded color spectrum helps them identify food, choose mates, and navigate landscapes with extraordinary precision. In fact, research shows that many bird species can detect polarized light and flicker rates up to 100 Hz, far beyond human capability. These adaptations make avian vision one of the most sophisticated in the animal kingdom.

The Biological Basis of Avian Vision

To understand how do birds see, it's essential to examine the structure of their eyes. Bird eyes are proportionally larger than those of mammals relative to body size, occupying up to 15% of their head mass. This large ocular volume allows for greater light intake and higher visual acuity. Their eyes are also tubular rather than spherical, which enhances focus and depth perception, particularly crucial for fast-flying species like hawks and swifts.

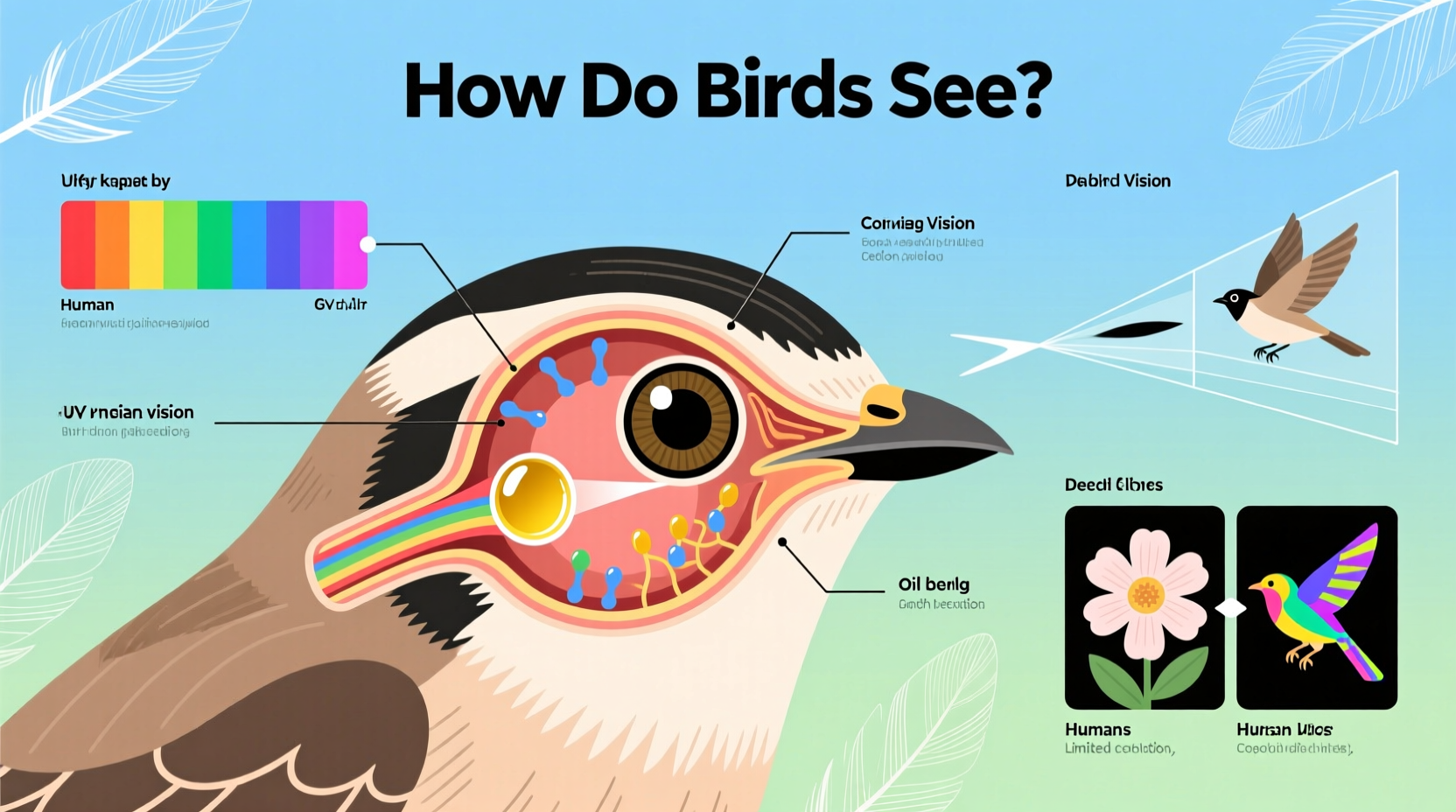

The retina contains photoreceptor cells: rods for low-light vision and cones for color detection. Most birds possess tetrachromatic vision, meaning they have four kinds of cone cells sensitive to red, green, blue, and ultraviolet wavelengths. This enables them to perceive colors invisible to humans—such as UV-reflective patterns on feathers or fruits. For example, many flowers and berries reflect UV light, making them stand out vividly to birds even in dim forest understories.

Additionally, birds have a specialized structure called the pecten oculi, a vascular fold projecting into the vitreous humor. It nourishes the retina and may reduce glare, improving contrast sensitivity—an advantage during high-speed flight or hunting.

Visual Acuity and Field of View

One of the most remarkable aspects of how birds see involves their exceptional visual acuity. Raptors such as eagles and falcons can spot prey from over a mile away. A golden eagle, for instance, has visual acuity estimated at 2.5 times that of a human. This sharpness comes from a high density of photoreceptors in the fovea—the central region of the retina responsible for detailed vision. Some birds even have two foveae per eye: one for forward viewing and another for lateral scanning, enabling simultaneous focus on distant and peripheral objects.

Field of view varies significantly among species depending on eye placement. Prey birds like pigeons and ducks have eyes positioned on the sides of their heads, granting nearly 360-degree panoramic vision to detect predators. However, this wide field sacrifices binocular overlap and depth perception. Conversely, predatory birds like owls and hawks have front-facing eyes, providing strong stereoscopic vision critical for judging distance when diving on prey.

| Bird Type | Field of View (Degrees) | Binocular Overlap | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon | ~300 | 20° | Predator detection |

| Barn Owl | 110 | 70° | Depth perception for hunting |

| Peregrine Falcon | 145 | 55° | High-speed pursuit |

| European Robin | 180 | 30° | Foraging and navigation |

Night Vision and Low-Light Adaptations

While most birds are diurnal, some, like owls, are highly adapted for nocturnal vision. Owls possess extremely large eyes with a high concentration of rod cells, enhancing sensitivity in near-darkness. Their tubular eye shape increases light-gathering capacity, while a reflective layer behind the retina—the tapetum lucidum—bounces unabsorbed light back through the photoreceptors, effectively doubling its use. This is why owl eyes often appear to glow in the dark.

However, not all night-active birds rely solely on vision. Nightjars and nighthawks use a combination of acute hearing and motion detection to locate insects in low light. Still, their ability to discern movement and silhouettes against moonlit skies demonstrates a refined adaptation within the broader context of how birds see after sunset.

Color Perception and Ultraviolet Vision

Perhaps one of the most intriguing answers to how do birds see lies in their color perception. Birds can distinguish subtle variations in plumage that appear identical to humans. Many songbirds, for example, display UV-reflective patches on their feathers that play a role in mate selection. Female blue tits prefer males with brighter UV crown patches, indicating better health and genetic fitness.

This UV sensitivity extends beyond social signaling. Raptors like kestrels can track voles by detecting UV-reflective urine trails, giving them a significant hunting advantage. Similarly, hummingbirds use UV cues to locate nectar-rich flowers, which often have UV nectar guides directing pollinators to the source.

It’s important to note that not all birds see UV light equally. Some species, such as pigeons and chickens, have oil droplets in their cone cells that filter out UV wavelengths. These droplets act like built-in sunglasses, protecting the retina while fine-tuning color discrimination under bright conditions.

Motion Detection and Flicker Fusion Rate

Another key aspect of how birds see involves temporal resolution—how quickly they process changes in light. Birds generally have a much higher flicker fusion rate (FFF) than humans. While we stop perceiving flicker at around 60 Hz, many birds can detect flicker up to 100 Hz or more. This means they experience artificial lighting, such as LED lights or computer screens, as rapidly flashing rather than continuous.

This high FFF is especially beneficial for birds in flight. Swifts and swallows, which maneuver through cluttered environments at high speeds, rely on rapid visual processing to avoid collisions. It also explains why birds may be startled by seemingly steady indoor lights—they actually perceive them as strobing.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Vision

Beyond biology, the way birds see has inspired cultural metaphors across civilizations. In Native American traditions, the eagle’s keen eyesight symbolizes spiritual insight and divine perspective. The phrase “eagle-eyed” entered common usage to describe someone with exceptional observational skills. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, the falcon-headed god Horus represented omniscience and royal authority, his eyes believed to watch over the land.

In modern psychology, bird vision is sometimes used as a metaphor for mindfulness and expanded awareness. The idea of seeing “the bigger picture,” like a raptor soaring above, encourages people to rise above immediate concerns and gain clarity. Understanding how do birds see thus transcends science, influencing philosophy, art, and personal development.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers

For birdwatchers, appreciating avian vision can enhance observation techniques. Since birds perceive UV light, clothing that appears dull to us might be glaringly bright to them. Wearing UV-free or neutral-toned attire reduces visibility and increases chances of close encounters. Avoiding scented products and moving slowly also helps, as birds combine visual input with other senses to assess threats.

Using optics designed to mimic natural light transmission improves viewing accuracy. High-quality binoculars with full-spectrum coatings allow observers to see plumage details closer to what birds themselves perceive. Additionally, visiting habitats during early morning or late afternoon—when UV reflection is strongest—can reveal hidden patterns on feathers and plants.

Photographers should consider UV reflectance when capturing images. Standard camera sensors block UV light, so specialized filters or modified cameras may be needed to document true avian coloration. Post-processing tools can simulate UV-enhanced views, offering insights into how do birds see their environment.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Vision

A widespread myth is that birds have poor night vision. While most are diurnal, several species—including owls, nightjars, and kiwis—have evolved excellent low-light capabilities. Another misconception is that all birds see in slow motion. While their higher flicker fusion rate suggests faster visual processing, this doesn’t mean they experience time differently; rather, they simply resolve rapid movements more clearly.

Some believe that birds cannot recognize individual humans. Yet studies show crows, parrots, and gulls can distinguish human faces and remember threatening individuals for years—a testament to their advanced visual memory and cognitive abilities.

How to Support Bird Vision in Urban Environments

Modern infrastructure poses challenges to avian vision. Glass windows, invisible to birds due to reflections of sky or trees, cause millions of collisions annually. Applying UV-reflective decals or patterned films breaks up these illusions, making glass visible to birds without obstructing human views.

Cities can adopt bird-friendly lighting policies by minimizing blue-rich white LEDs at night, which disorient migratory species. Using downward-facing, shielded fixtures reduces skyglow and preserves natural celestial cues birds use for navigation.

FAQs About How Birds See

- Can birds see in the dark?

- Yes, nocturnal birds like owls have highly adapted eyes with more rod cells and larger pupils, allowing them to see well in low light. However, most birds are diurnal and have limited night vision.

- Do birds see color better than humans?

- Most birds do. With four types of cone cells—including sensitivity to ultraviolet light—they perceive a broader and more nuanced color spectrum than humans, who only have three cone types.

- Why do birds collide with windows?

- Birds often don’t recognize glass as a barrier because it reflects the sky or vegetation. Since they see UV light, adding UV-visible markers can help prevent collisions.

- Can birds see television or phone screens?

- They can see the images, but likely perceive them as flickering due to their high flicker fusion rate. Rapid screen refreshes may appear unstable or unnatural to them.

- How far can birds see?

- It varies by species. Eagles can spot small animals from over a mile away, while smaller birds typically have shorter visual ranges, optimized for their ecological niche.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4