Birds don't talk in the human sense, but they communicate through complex vocalizations and body signalsâa process often described as how do birds talk in everyday language. While they lack vocal cords, birds produce sounds using a unique organ called the syrinx, located at the base of their trachea. These calls and songs serve essential functions such as attracting mates, defending territory, warning of predators, and maintaining social bonds. Understanding how birds develop their vocal abilities, how species differ in communication styles, and how some birds mimic human speech provides insight into both avian biology and cultural symbolism.

The Biology Behind Bird Vocalization: How Do Birds Produce Sound?

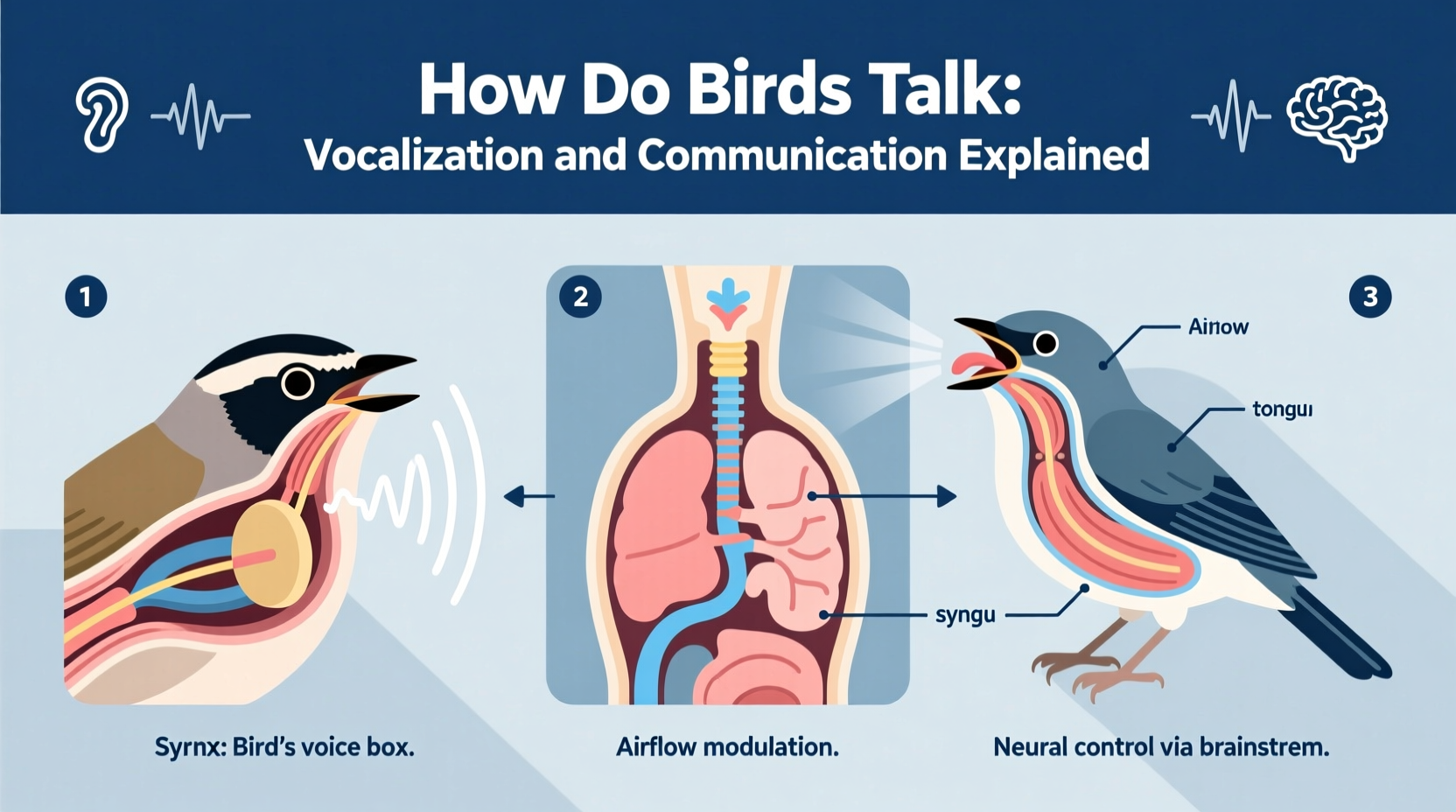

Unlike mammals, birds do not have vocal cords. Instead, sound production occurs in the syrinx, a specialized structure where the trachea splits into the bronchi leading to the lungs. The syrinx contains vibrating membranes and muscles that can be finely controlled, allowing birds to produce a wide range of tones, frequencies, and rhythmsâsometimes even two sounds at once.

The complexity of a birdâs song is directly related to the number of muscles controlling the syrinx. Songbirds (oscine passerines), such as canaries, robins, and mockingbirds, possess up to eight pairs of muscles, enabling intricate melodies. In contrast, non-songbirds like pigeons or hawks have fewer muscles and produce simpler calls.

Auditory feedback plays a crucial role during development. Young birds go through a sensorimotor phase where they listen to adult models (usually their parents), memorize the sounds, and gradually refine their own vocalizations through practiceâsimilar to how human infants learn language.

Which Birds Can Mimic Human Speech?

When people ask how do birds talk, they often mean: why can some birds imitate human words? Only a few bird groups have this ability, primarily parrots, mynas, and certain corvids like crows and ravens.

- Parrots (Psittaciformes): African grey parrots, Amazon parrots, and budgerigars are renowned for mimicking human speech with clarity. Studies show African greys can associate words with meanings, demonstrating cognitive understanding beyond mere repetition.

- Mynah Birds: Particularly the common hill mynah, known for clear, loud mimicry and often kept as pets for their talking ability.

- Corvids: Crows and ravens can mimic human speech in captivity, though less commonly than parrots. Their intelligence supports advanced learning, including tool use and problem-solving.

These birds possess a highly developed song control system in the brain, consisting of interconnected nuclei responsible for learning, producing, and recognizing complex sounds. This neural architecture allows them to process auditory information and reproduce novel sounds accurately.

Do Birds Understand What They're Saying?

Most birds that mimic human speech do so without full comprehension. However, research on certain individualsâespecially in controlled environmentsâshows exceptions. For example, Alex the African Grey Parrot, studied by Dr. Irene Pepperberg, demonstrated an understanding of concepts like color, shape, quantity, and absence. He could answer questions like "What color is the key?" correctly, indicating symbolic thought.

In the wild, bird communication is functional rather than referential. Alarm calls may specify predator type (e.g., aerial vs. ground threat), and mating songs convey fitness. But these signals are instinctive or learned within species-specific contextsânot abstract language.

| Bird Group | Vocal Learning Ability | Can Mimic Humans? | Brain Structure Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Songbirds (e.g., Nightingales) | High (learn songs from tutors) | Rarely | Advanced song nuclei |

| Parrots | Very High | Yes, clearly | Highly developed vocal centers |

| Mynahs | High | Yes | Well-developed pathways |

| Ducks & Chickens | Low (mostly innate calls) | No | Limited vocal learning regions |

| Crows & Ravens | Moderate to High | Sometimes in captivity | Complex forebrain |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Talking Birds

Beyond biology, the idea of how do birds talk carries deep cultural resonance. Across civilizations, speaking birds symbolize wisdom, prophecy, or spiritual messages.

- In Hindu mythology, the sage Kakabhushundi is depicted as a talking crow who witnessed cosmic cycles, representing eternal knowledge.

- In Native American traditions, ravens are seen as tricksters and creators, often credited with bringing fire or language to humans. \li>In Victorian England, owning a talking parrot was a status symbol, reflecting global trade and intellectual curiosity about animal minds.

- In modern media, characters like Iago (from Disney's Aladdin) or Paulie the parrot reflect both fascination and caution around animals that mimic human speech.

These narratives reveal humanityâs enduring quest to interpret non-human communicationâand perhaps project our desire for connection onto creatures that seem to speak our language.

How Environment and Social Interaction Shape Bird Speech

Vocal learning in birds depends heavily on early exposure and social context. A young bird isolated from adults will develop abnormal or incomplete songs. Similarly, pet parrots raised with frequent human interaction are far more likely to mimic speech than those kept alone.

Urban environments also influence bird communication. Studies show that city-dwelling birds like great tits and sparrows sing at higher pitches to overcome low-frequency traffic noise. Some adjust their singing times to quieter hours, such as dawn or late evening.

This adaptability highlights the importance of auditory environment in shaping how birds communicate. It also suggests that habitat loss and noise pollution could disrupt natural vocal behaviors, affecting mating success and survival.

Teaching Your Pet Bird to 'Talk': Practical Tips

If you're curious about how do birds talk and want to encourage vocal mimicry in a pet bird, consider these science-backed strategies:

- Start Early: Young birds (under one year) are most receptive to learning new sounds.

- Repeat Clearly and Consistently: Use short phrases like "Hello!" or "Pretty bird!" spoken slowly and clearly multiple times daily.

- Pair Words with Actions: Say "Want food?" while offering a treat to create associative learning.

- Use Positive Reinforcement: Reward attempts at mimicry with praise, attention, or small treats (if safe for the species).

- Minimize Background Noise: Train in quiet settings so your bird can focus on your voice.

- Be Patient: Not all birds will talk, even within highly capable species. Individual personality and health play major roles.

Species like budgies, cockatiels, and green amazons tend to be more responsive than others. Avoid forcing interaction; stress inhibits learning.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Speech

Despite growing scientific understanding, several myths persist about how birds talk:

- Myth: All birds can learn to talk. Truth: Only three groupsâparrots, songbirds, and hummingbirdsâshow strong vocal learning. Most birds rely on innate calls.

- Myth: Talking birds understand everything they say. Truth: While some grasp basic concepts, most mimicry is rote repetition without semantic meaning.

- Myth: Birds talk just like humans. Truth: Their anatomy and neural pathways differ significantly. They donât form words using lips, tongue, or teeth but reshape airflow through the syrinx and beak.

- Myth: Electronic devices help birds learn faster. Truth: Recordings lack social context. Birds learn best from live interaction.

Regional Differences in Bird Communication

Just as human languages vary by region, so do bird dialects. Populations of the same species separated geographically may develop distinct songs. For instance, white-crowned sparrows in Northern California sing differently from those in Southern California.

These regional variations arise due to isolation, environmental acoustics, and cultural transmission. Ornithologists use dialect mapping to study population movements, genetic flow, and habitat fragmentation.

For birdwatchers, recognizing local dialects enhances identification accuracy, especially in dense forests where visual spotting is difficult.

How to Observe and Interpret Wild Bird Communication

Understanding how birds talk enriches the experience of birdwatching. Hereâs how to interpret natural vocalizations:

- Dawn Chorus: Most active between 4â7 AM, when atmospheric conditions carry sound farther. Males sing to declare territory and attract mates.

- Alarm Calls: Short, sharp notes (e.g., chick-a-dee-dee-dee in titmice) often signal danger. More âdeesâ indicate higher threat levels.

- Contact Calls: Softer chirps maintain group cohesion during foraging or flight.

- Flight Songs: Some birds, like larks, sing while flying to display fitness.

Use a field guide or app (like Merlin Bird ID or Audubon Bird Guide) to match calls with species. Recording apps can help compare your observations with reference libraries.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can any bird learn to talk?

- No. Only certain speciesâmainly parrots, mynas, and some corvidsâcan mimic human speech. Most birds communicate through species-specific calls and songs.

- Why can parrots talk but other birds canât?

- Parrots have evolved advanced brain structures for vocal learning and exceptional control over their syrinx and respiratory system, enabling precise sound reproduction.

- Do birds think in language?

- No evidence suggests birds think in human-like language. They process sounds and symbols differently, relying on instinct, memory, and learned cues for survival.

- At what age do birds start talking?

- Pet parrots typically begin mimicking sounds between 3â12 months, depending on species and individual development. Wild birds finalize their songs within their first year.

- Is it cruel to teach birds to talk?

- Not if done humanely. However, excessive noise, isolation, or forced training causes stress. Birds should be kept in enriched environments with social companionship.

In summary, while birds do not talk in the linguistic sense, their vocalizations represent a sophisticated blend of biology, learning, and adaptation. Exploring how do birds talk reveals not only the mechanics of avian sound production but also the evolutionary roots of communication itself. Whether observing wild songsters at dawn or interacting with a talking parrot at home, we gain deeper appreciation for natureâs diverse ways of conveying meaning.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4