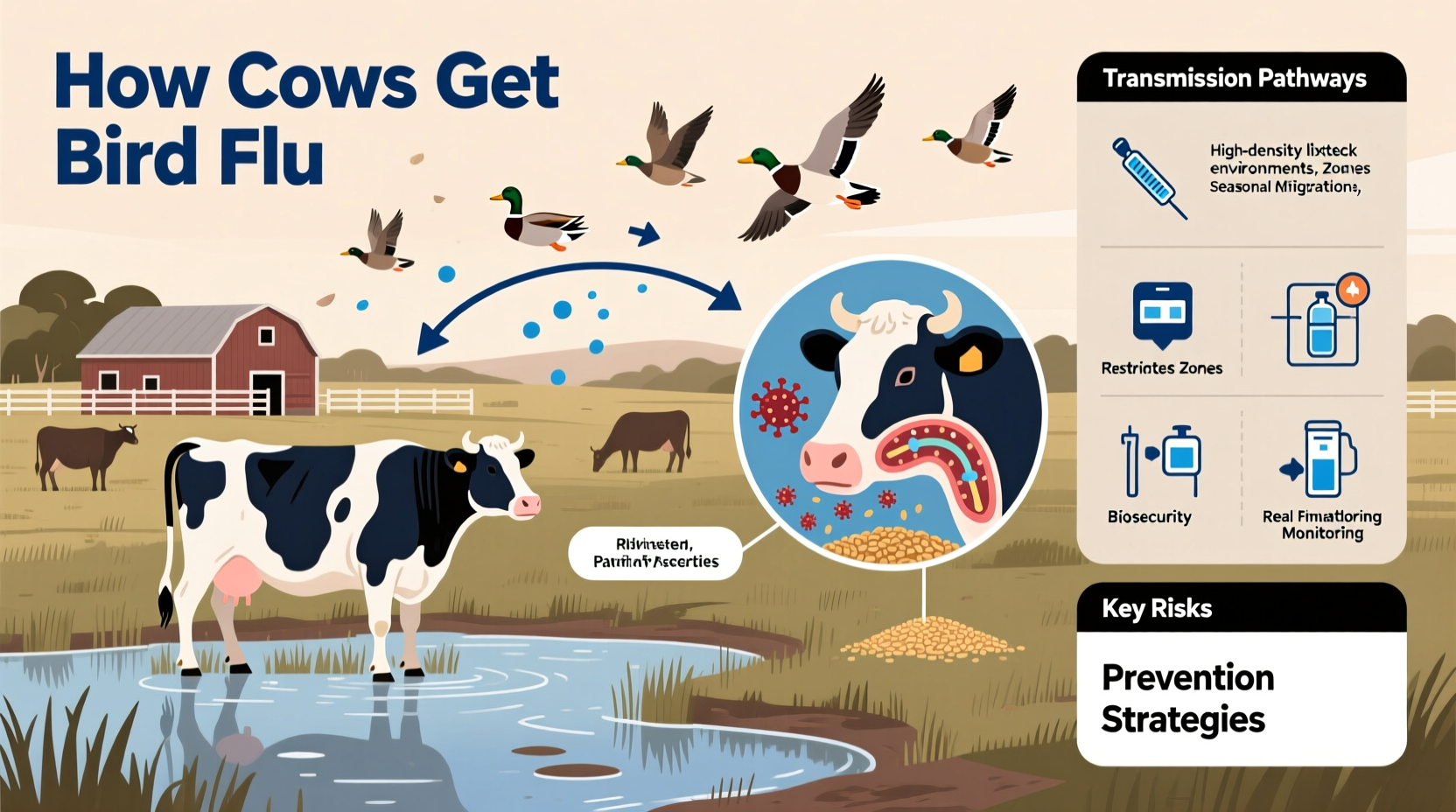

Cows can become infected with bird flu, specifically avian influenza viruses like H5N1, through direct or indirect exposure to infected birds or contaminated environments. While avian influenza primarily affects wild and domestic birds, recent evidence shows that under certain conditions, the virus can spill over into mammals—including cattle. The most likely pathway for cows getting bird flu involves contact with secretions from infected wild birds, particularly through shared water sources or feed contaminated with bird droppings. This emerging transmission pattern, sometimes referred to as 'how do cows get bird flu in 2024,' highlights a growing concern among agricultural and public health officials about interspecies viral spread.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Evolution

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is caused by type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, serving as silent reservoirs. The H5N1 strain, first identified in 1996 in geese in China, has evolved into multiple clades and subclades, some of which have demonstrated increased ability to infect non-avian species.

The global spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 accelerated in the early 2020s, affecting millions of birds across Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America. By 2024, outbreaks were reported not only in poultry farms but also in an expanding range of mammals, including foxes, seals, sea lions—and notably, dairy cattle. This shift raised alarms about the virus’s potential to adapt to new hosts, increasing the risk of sustained mammalian transmission.

How Bird Flu Reaches Cattle: Transmission Pathways

Despite being mammals and not natural hosts for avian influenza, cows are now recognized as susceptible under specific environmental and management conditions. The question of how cows get bird flu centers on three primary routes of exposure:

- Contact with infected wild birds: Migratory birds carrying H5N1 can defecate in pastures, watering troughs, or feed storage areas used by cattle. Inhalation of aerosolized particles or ingestion of contaminated material can lead to infection.

- Contaminated equipment or personnel: Farmers, veterinarians, or transport vehicles moving between infected poultry farms and cattle operations may inadvertently transfer the virus via boots, clothing, or tools.

- Intermediate vectors: Flies, rodents, or other animals that come into contact with infected bird carcasses or feces may act as mechanical carriers, introducing the virus into barnyards or milking parlors.

In several confirmed U.S. cases in 2024, affected dairy herds showed signs of respiratory distress and reduced milk production. Genetic sequencing revealed nearly identical H5N1 strains in local wild birds and infected cows, supporting environmental transmission.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Cows

Unlike birds, where HPAI causes rapid death, infected cattle tend to exhibit milder clinical signs, making detection challenging. Key symptoms observed include:

- Decreased milk yield (often the first noticeable sign)

- Fever and lethargy

- Nasal discharge and coughing

- Reduced appetite

- Abnormal milk appearance (e.g., watery, discolored)

Notably, mortality rates in cattle remain low compared to poultry, but the presence of the virus in milk raises significant food safety and zoonotic concerns. In March 2024, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) confirmed H5N1 in raw milk samples from infected herds, prompting investigations into pasteurization efficacy and consumer risks.

Biological Barriers and Viral Adaptation

Mammals, including cows, possess physiological differences from birds that typically limit avian influenza infection. For example, bird flu viruses prefer binding to alpha-2,3-linked sialic acid receptors, predominantly found in avian intestinal and respiratory tracts, whereas mammals have more alpha-2,6-linked receptors in their upper airways.

However, recent studies suggest that some H5N1 variants may be acquiring mutations—such as changes in the hemagglutinin protein—that enhance binding to mammalian-type receptors. Additionally, high viral loads in the environment may overwhelm natural defenses, allowing initial infection even without perfect receptor compatibility.

This adaptation process underscores why monitoring cow infections is critical—not just for agriculture, but for pandemic preparedness. If H5N1 gains efficient transmission between mammals, it could pose a serious public health threat.

Geographic and Seasonal Patterns of Cow Infections

As of mid-2024, bird flu cases in cattle have been reported primarily in the United States, particularly in Texas, Kansas, Michigan, and Idaho. Most incidents occurred during spring migration periods when large numbers of infected wild birds move through central flyways overlapping with major dairy regions.

Seasonality plays a key role: outbreaks tend to peak between February and May, coinciding with increased bird movement and calving seasons—times when cattle may experience stress-induced immune suppression, increasing susceptibility.

In contrast, no widespread cow infections have been reported in the European Union or Australia, though surveillance systems vary. Differences in farming practices—such as indoor housing versus pasture grazing—may influence exposure risk.

| Region | First Confirmed Cow Case | Possible Transmission Source | Regulatory Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | March 2024 | Wild bird contamination of feed/water | USDA monitoring, milk testing |

| Canada | Under investigation | Potential cross-border spread | Enhanced biosecurity alerts |

| European Union | No confirmed cases | Limited spillover observed | Ongoing surveillance |

Public Health Implications and Food Safety

A major concern arising from cows getting bird flu is the potential for human exposure, especially through unpasteurized dairy products. While no human cases have been linked to consuming milk from infected cows, the CDC warns that close contact with sick animals—such as farmworkers or veterinarians—poses a higher risk.

Pasteurization effectively inactivates H5N1 in milk, according to preliminary FDA tests, meaning commercially processed dairy products are considered safe. However, raw milk consumption, legal in many states, presents a potential hazard. Public health agencies recommend avoiding raw milk during outbreaks.

Additionally, slaughterhouse workers handling infected animals must use personal protective equipment (PPE), as respiratory droplets and bodily fluids can harbor live virus.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures for Farms

Preventing bird flu in cattle requires a multi-layered biosecurity approach. Producers should consider the following actionable steps:

- Isolate livestock from wild birds: Cover feed bins, use enclosed watering systems, and install bird netting around barns.

- Monitor wildlife activity: Report sick or dead birds near farms to local agricultural authorities immediately.

- Implement strict hygiene protocols: Disinfect boots, vehicles, and equipment before entering animal areas.

- Limit movement between species: Avoid using the same tools or clothing for poultry and cattle operations.

- Test suspect animals promptly: Early detection allows for containment and reduces spread.

Veterinary diagnostic labs now offer PCR testing for H5N1 in bovine nasal swabs and milk samples. The USDA provides funding for testing and compensation for depopulated flocks, though cattle are not currently subject to mandatory culling unless severely ill.

Common Misconceptions About Cows and Bird Flu

Several myths persist about how cows get bird flu and what it means for consumers:

- Misconception: 'Bird flu spreads easily between cows.'

Fact: There is no evidence of sustained cow-to-cow transmission. Most cases appear to result from independent environmental exposure. - Misconception: 'Drinking milk can give you bird flu.'

Fact: Pasteurized milk is safe. Only raw, untreated milk from infected herds poses a theoretical risk. - Misconception: 'Cows are turning into bird flu carriers like poultry.'

Fact: Cattle are incidental hosts. They do not amplify or spread the virus at the scale seen in birds.

What Researchers Are Watching in 2024 and Beyond

Scientists are closely tracking genetic changes in H5N1 isolates from cattle to assess whether the virus is adapting to mammals. Particular attention is focused on mutations in the PB2 gene (associated with replication in cooler mammalian airways) and hemagglutinin stability.

Increased surveillance in dairy herds, especially in high-risk migratory zones, is being implemented. Some experts advocate for developing veterinary vaccines for cattle, though none are currently approved.

The broader implication is clear: the line between animal health and human pandemic risk is blurring. Understanding how cows get bird flu isn’t just about protecting livestock—it’s about preventing the next zoonotic leap.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can humans get bird flu from cows?

There is no confirmed case of human infection from cows as of mid-2024. However, the CDC considers close contact with infected animals a potential risk and advises protective measures for farmworkers.

Is it safe to drink milk during a bird flu outbreak?

Yes, if the milk is pasteurized. Heat treatment destroys the virus. Avoid raw milk, especially from areas with known infections.

Do infected cows need to be culled?

Currently, there is no mandatory culling policy for H5N1-infected cattle in the U.S. Decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, focusing on animal welfare and containment.

Can bird flu spread from cows to other farm animals?

While possible, there is no evidence of widespread transmission to other species. However, pigs—which can host both avian and human flu strains—should be kept separate as a precaution.

How can farmers report suspected bird flu in cattle?

Farmers should contact their state veterinarian or local USDA office immediately. Rapid reporting enables faster testing and helps prevent wider outbreaks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4