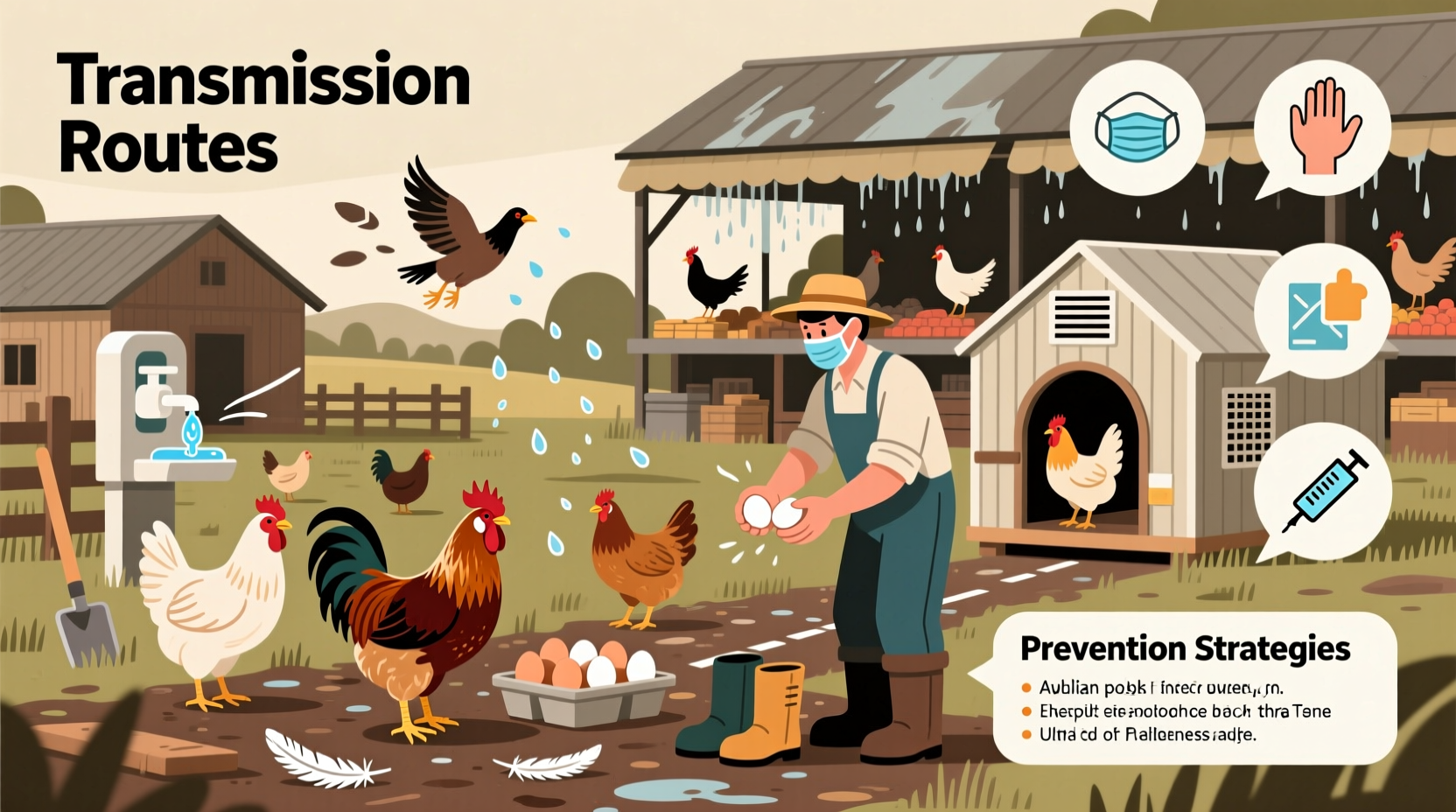

Humans contract bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily through direct contact with infected birds or their secretions, including saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'how do humans get bird flu from poultry' highlights a common transmission route—exposure to live or dead infected chickens, ducks, or other domesticated birds in markets, farms, or backyard flocks. While human-to-human transmission remains rare, the primary risk arises when individuals inhale aerosolized particles near contaminated environments or touch infected surfaces and then their face. Understanding how do humans contract bird flu is essential for prevention, especially in regions experiencing outbreaks among bird populations.

Understanding Bird Flu: What It Is and How It Spreads

Bird flu is caused by strains of the influenza A virus, most notably subtypes H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. These viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks and shorebirds, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. However, when these viruses jump to domestic poultry—such as chickens and turkeys—they can cause severe illness and high mortality rates in flocks.

The transmission to humans typically occurs at the animal-human interface. People who work closely with poultry—farmers, slaughterhouse workers, veterinarians, and live market vendors—are at increased risk. Infection happens not only through inhalation but also via contaminated tools, cages, water sources, or clothing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasizes that consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs does not transmit the virus, as heat destroys the pathogen.

Historical Context and Notable Outbreaks

The first documented case of human infection with H5N1 occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, where 18 people were infected and six died. This outbreak led to the culling of all poultry in the region—a drastic but effective measure. Since then, sporadic cases have emerged across Asia, Africa, Europe, and parts of the Middle East, particularly during major migratory bird seasons.

In 2003, another wave hit several countries including South Korea, Vietnam, and Thailand. More recently, in 2022 and 2023, multiple countries reported H5N1 detections in both wild and commercial birds, with limited human cases in Cambodia, China, and the United States. For example, in April 2022, a person in Colorado tested positive after culling infected poultry—an occupational exposure scenario.

These events underscore the evolving nature of avian influenza and its potential to cross species barriers. Although sustained human-to-human transmission has not been observed, each case raises concerns about viral mutations that could enhance transmissibility.

Biological Mechanisms Behind Human Infection

To understand how do humans contract bird flu, it's important to examine the biology of viral entry. Avian influenza viruses bind preferentially to alpha-2,3-linked sialic acid receptors, which are found deep in the human lower respiratory tract—not in the upper airways where seasonal flu viruses attach. This explains why bird flu tends to cause severe pneumonia rather than mild cold-like symptoms.

When a person inhales droplets containing the virus or transfers it from contaminated hands to mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth), the virus may infect cells in the lungs. Once inside, it replicates rapidly, triggering an aggressive immune response that can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The fatality rate for confirmed H5N1 cases is alarmingly high—over 50% according to WHO data—though this figure may be skewed due to underreporting of mild cases.

Mutations in the hemagglutinin protein of the virus could potentially allow better binding to human-type receptors, increasing pandemic risk. Surveillance programs monitor these genetic changes closely, especially in areas where pigs—known mixing vessels for influenza strains—are raised alongside poultry.

High-Risk Groups and Geographic Hotspots

Certain populations face greater exposure risks based on occupation, location, or cultural practices. Rural communities in Southeast Asia, where backyard poultry farming is common, report more frequent spillover events. Live bird markets, prevalent in many Asian cities, create ideal conditions for virus spread due to crowding, poor sanitation, and constant introduction of new birds.

In addition to farmers and bird handlers, travelers visiting affected regions should exercise caution. Those planning to tour rural farms or participate in agricultural activities should wear protective gear and avoid close contact with birds. Children playing near free-ranging chickens may unknowingly pick up the virus on toys or shoes.

North America and Europe have seen fewer human cases, largely due to stricter biosecurity measures and rapid response protocols. However, the widespread detection of H5N1 in wild birds across the U.S. and Canada since 2022 means vigilance remains critical. Hunters handling game birds or collecting feathers should use gloves and masks.

Prevention Strategies and Personal Protection Measures

Preventing bird flu transmission hinges on minimizing contact with potentially infected animals and environments. Key recommendations include:

- Avoid visiting live bird markets or poultry farms in areas with active outbreaks.

- Wear personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gloves and N95 respirators, when working with birds.

- Practice thorough hand hygiene after any interaction with birds or their habitats.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly (internal temperature of at least 165°F or 74°C).

- Report sick or dead birds to local wildlife or agricultural authorities.

Public health agencies recommend vaccination for poultry in high-risk zones, though no widely available human vaccine currently exists for H5N1. Experimental vaccines are being developed and stockpiled for emergency use in case of a pandemic.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how do humans contract bird flu. One common misconception is that eating chicken or eggs spreads the disease. As previously noted, proper cooking eliminates the virus. Another myth suggests that bird flu spreads easily between people. To date, only isolated instances of possible limited human-to-human transmission have been recorded, usually involving prolonged, unprotected contact with severely ill patients.

Some believe that urban pet birds pose a significant threat. While companion parrots or canaries can theoretically become infected, the likelihood is extremely low unless exposed to wild migratory birds. Indoor birds kept away from external contamination sources are generally safe.

There’s also confusion around airborne transmission. While small droplets can carry the virus short distances in barns or enclosures, bird flu is not considered truly airborne like measles or tuberculosis. Close proximity to infected birds in poorly ventilated spaces increases risk, but casual outdoor encounters do not.

Surveillance, Reporting, and Global Response Efforts

International cooperation plays a vital role in controlling avian influenza. Organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) coordinate surveillance, share genetic sequencing data, and support outbreak response.

National governments implement early warning systems using sentinel farms, laboratory testing, and remote monitoring of wild bird migrations. Rapid reporting allows for timely culling, movement restrictions, and public advisories. In the U.S., the USDA operates the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP), which sets standards for flock certification and disease control.

Citizens can contribute by participating in citizen science initiatives, such as reporting unusual bird deaths through platforms like eBird or local wildlife hotlines. Timely information helps authorities contain outbreaks before they escalate.

| Transmission Route | Risk Level | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Direct contact with infected birds | High | Use gloves and mask; avoid touching sick/dead birds |

| Inhalation of contaminated dust/aerosols | Moderate | Work in well-ventilated areas; wear respirator |

| Consumption of cooked poultry/eggs | None | Cook thoroughly to 165°F (74°C) |

| Human-to-human contact | Very Low | Follow infection control if caring for patient |

| Contact with contaminated surfaces | Low to Moderate | Disinfect tools, boots, and equipment regularly |

What to Do If You Suspect Exposure

If you’ve had close contact with birds in an area with confirmed avian flu activity and develop symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, or difficulty breathing within 10 days, seek medical attention immediately. Inform your healthcare provider about the potential exposure so they can take appropriate precautions and order diagnostic tests.

Antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) may be prescribed prophylactically or therapeutically, although their effectiveness against certain strains varies. Early treatment improves outcomes significantly. Infected individuals may be isolated to prevent secondary transmission while investigations determine the source.

Future Outlook and Pandemic Preparedness

As climate change alters migration patterns and global trade increases animal movement, the risk of zoonotic spillover events—including bird flu—is expected to rise. Strengthening veterinary infrastructure, improving farm biosecurity, and investing in universal flu vaccines are key strategies for long-term prevention.

Pandemic preparedness plans now include specific protocols for avian influenza, covering everything from vaccine deployment to travel advisories. Public awareness campaigns help ensure communities know how do humans contract bird flu and what steps to take to stay safe.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can I get bird flu from watching birds in my backyard?

No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected birds or their droppings. - Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

There is no commercially available vaccine for the general public, but experimental vaccines exist for stockpiling in emergencies. - How long does the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

The virus can remain infectious for days in cool, moist conditions—up to two weeks in water—and shorter periods in dry, sunny environments. - Are all bird species capable of spreading bird flu?

Most cases involve waterfowl and poultry. Songbirds and raptors can become infected but are less commonly involved in transmission to humans. - Should I stop feeding wild birds to avoid bird flu?

During outbreaks, authorities may recommend pausing bird feeders to reduce congregation. Clean feeders regularly with a 10% bleach solution if used.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4