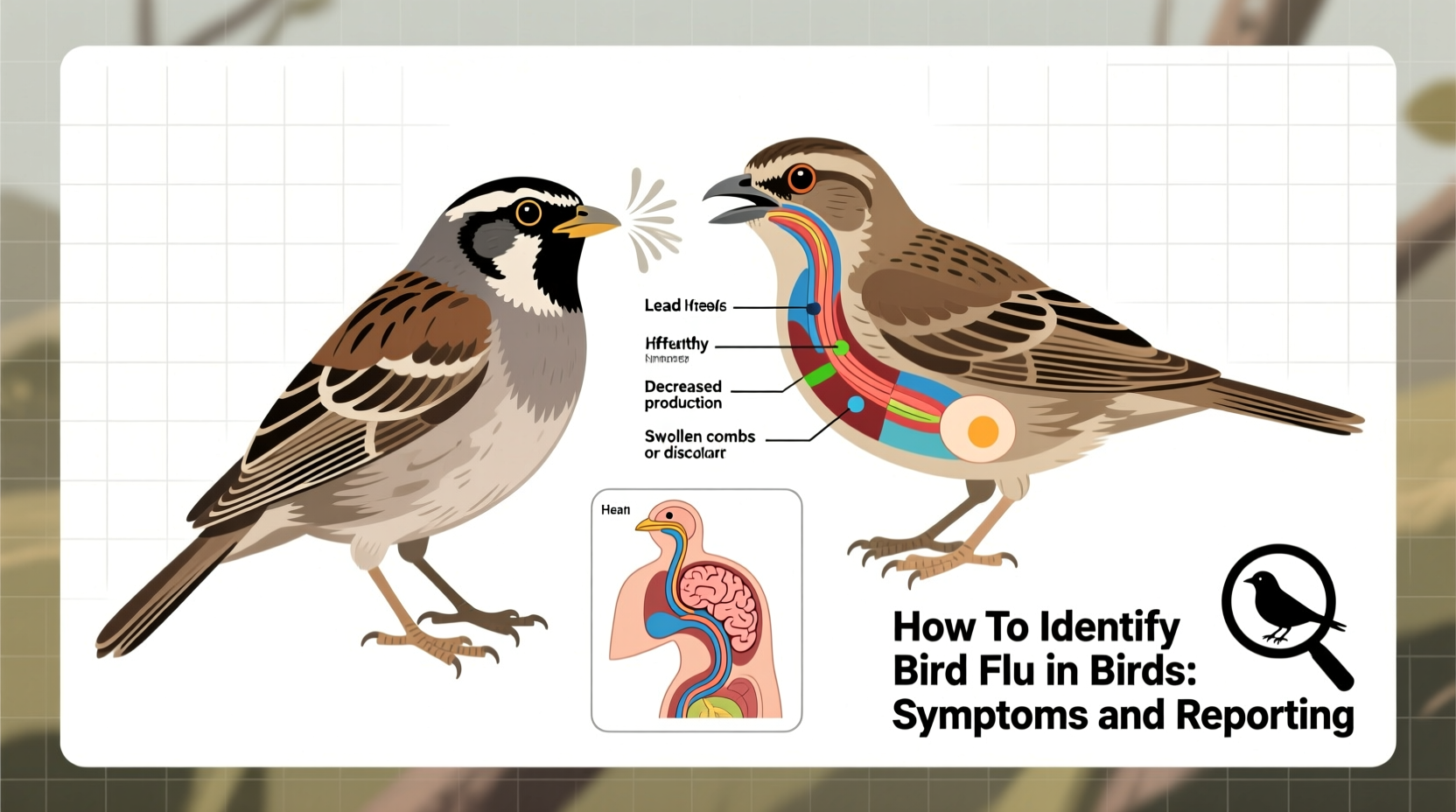

One of the most pressing concerns for bird watchers, poultry farmers, and wildlife enthusiasts is knowing how to tell if a bird has bird flu. Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, can be identified by observing specific clinical signs such as sudden death, ruffled feathers, decreased food and water intake, swelling around the head and neck, nasal discharge, breathing difficulties, and a significant drop in egg production in domesticated birds. Recognizing these symptoms early—particularly phrases like 'how do you know if a bird has bird flu' or 'signs of bird flu in wild birds'—is essential for preventing widespread outbreaks.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Wild and Domestic Birds

Bird flu, caused primarily by Influenza A viruses (especially subtypes H5 and H7), affects both wild and domestic bird populations. The severity of the disease varies depending on the virus strain—classified as either low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) or high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). While LPAI may cause mild respiratory issues or go unnoticed, HPAI spreads rapidly and often leads to high mortality rates.

In wild birds, especially waterfowl like ducks and geese, symptoms can be subtle. These birds often act as carriers without showing illness, making surveillance challenging. However, when symptoms do appear, they include:

- Sudden death without prior signs

- Lack of energy and appetite

- Purple discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs

- Soft-shelled or misshapen eggs

- Neurological signs such as tremors, lack of coordination, or twisting of the head and neck

- Diarrhea

Domestic poultry, including chickens, turkeys, and guinea fowl, are more susceptible to severe forms of the disease. In commercial flocks, bird flu can wipe out entire populations within 48 hours. Farmers monitoring their birds should look for rapid spread of respiratory distress, gasping, coughing, and a sharp decline in egg laying. If you're asking 'how can I tell if a wild bird has bird flu,' it's important to avoid direct contact and report sick or dead birds to local wildlife authorities.

Transmission and Risk Factors

Bird flu spreads through direct contact with infected birds’ saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Contaminated surfaces such as feeders, water sources, cages, and even footwear can serve as transmission vectors. Migratory birds play a critical role in spreading the virus across regions and continents, especially during seasonal migrations.

Factors that increase the risk of bird flu transmission include:

- High-density poultry farming

- Mixing domestic birds with wild populations

- Poor biosecurity practices on farms

- Use of untreated water from ponds frequented by wild waterfowl

- Live bird markets with inadequate sanitation

Understanding how bird flu spreads helps answer questions like 'can humans get bird flu from touching a bird?' While rare, human infections have occurred, typically among people with close, prolonged exposure to infected poultry. The CDC emphasizes that proper handling and cooking of poultry products (to an internal temperature of 165°F) eliminates the risk of infection.

Geographic and Seasonal Patterns

Bird flu outbreaks are not evenly distributed—they follow migratory flyways and climate patterns. In North America, peaks often occur during spring and fall migration periods (March–May and September–November). Regions near major wetlands or along the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific flyways see higher surveillance activity.

In 2022 and 2023, the United States experienced one of its largest HPAI outbreaks, affecting over 58 million birds across 47 states. Europe and parts of Asia reported similar surges, particularly in countries with dense poultry industries adjacent to natural waterfowl habitats.

If you’re wondering 'is bird flu still around in 2024?', the answer is yes. Ongoing monitoring by agencies like the USDA, WHO, and OIE confirms sporadic cases in both wild and commercial birds. Seasonal vigilance remains crucial, especially for backyard flock owners and birdwatchers who frequent wetland areas.

How to Report a Suspected Case

If you observe a bird displaying signs of bird flu, do not attempt to handle or treat it. Instead, follow these steps:

- Keep your distance and prevent pets or other animals from contacting the bird.

- Note the species (if identifiable), location, number of affected birds, and symptoms observed.

- Contact your state’s department of agriculture, wildlife agency, or use national reporting systems such as the USDA’s toll-free hotline (1-866-536-7593) or online portal.

- For dead wild birds, some jurisdictions recommend reporting clusters of five or more dead waterfowl or raptors.

Many states provide interactive maps and real-time updates on confirmed cases. For example, the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) maintains a public dashboard tracking detections nationwide.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Preventing bird flu requires proactive biosecurity, especially for those raising poultry. Key strategies include:

| Practice | Description | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Isolate new birds | Quarantine new additions for at least 30 days before introducing them to a flock. | High |

| Control access | Limit visitors to coops; require disinfection of shoes and equipment. | High |

| Clean water and feed sources | Use clean, treated water; avoid open ponds used by wild birds. | Moderate to High |

| Biosecure housing | House birds indoors or under netting to prevent contact with wild birds. | Very High |

| Disinfect regularly | Clean coops weekly with EPA-approved disinfectants effective against viruses. | High |

Backyard bird feeders have raised concerns during outbreaks. While there’s no conclusive evidence linking feeders directly to large-scale transmission, experts recommend taking them down temporarily during active HPAI events in your area—especially if sick or dead birds are reported nearby. This precaution aligns with searches like 'should I take down bird feeders due to bird flu in 2024?'

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds During Disease Outbreaks

Birds have long symbolized freedom, spiritual messengers, and omens across cultures. In times of disease, such symbolism shifts. Historical pandemics involving birds—such as the 1918 Spanish flu (linked indirectly to avian strains)—have influenced art, literature, and public perception.

In many Indigenous traditions, eagles and ravens are revered as sacred. When outbreaks affect these species, conservation takes on cultural urgency. Similarly, in East Asian cultures where poultry plays a central role in cuisine and festivals, bird flu can disrupt traditions and raise anxiety about food safety and spiritual purity.

This deeper context matters because public cooperation in surveillance and prevention depends not just on science but on cultural attitudes toward birds. Messaging that respects symbolic values while promoting health measures tends to be more effective.

Differences Between Bird Flu and Other Avian Illnesses

Not all sick-looking birds have bird flu. Conditions like Newcastle disease, avian pox, salmonellosis, and pesticide poisoning share overlapping symptoms. Accurate diagnosis requires laboratory testing, including RT-PCR or virus isolation from swabs taken from the cloaca or trachea.

Key differentiators:

- Newcastle disease: Also causes neurological signs but spreads more slowly than HPAI.

- Avian pox: Characterized by visible skin lesions rather than internal hemorrhaging.

- Salmonella: More common in young birds, causes diarrhea and weakness without respiratory swelling.

Only trained professionals should collect samples. Misdiagnosis based on appearance alone can lead to unnecessary panic or missed outbreaks.

Role of Citizen Science and Birdwatching Communities

Birdwatchers are on the front lines of early detection. Platforms like eBird and iNaturalist allow users to log sightings and unusual behaviors. When paired with official reporting channels, this data enhances outbreak modeling and response speed.

Tips for birders during bird flu season:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds.

- Do not use shared optics (binoculars, scopes) without disinfecting.

- Stick to designated trails to minimize habitat disturbance.

- Photograph sick birds from a distance and report them promptly.

Organizations like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology offer guidelines tailored to regional risks. Staying informed through trusted sources ensures that recreational birding doesn’t inadvertently contribute to disease spread.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can humans catch bird flu from wild birds?

Human cases are rare and usually involve direct, prolonged contact with infected poultry. Casual observation of wild birds poses negligible risk.

What should I do if I find a dead duck or goose?

Report it to your local wildlife agency. Do not touch it. Note the location and any visible symptoms like swelling or discolored skin.

Is it safe to eat eggs and chicken during a bird flu outbreak?

Yes, as long as poultry and eggs are properly cooked. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 165°F (74°C).

How long does bird flu survive in the environment?

The virus can persist in water for up to four days and in cold manure or soil for several weeks, especially in cooler temperatures.

Are songbirds affected by bird flu?

While less commonly affected than waterfowl, recent studies show some songbirds—including crows, jays, and sparrows—can contract and die from certain HPAI strains.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4