If you're wondering how do you know if your chicken has bird flu, the answer lies in recognizing a combination of clinical signs, behavioral changes, and confirmed laboratory testing. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), commonly known as bird flu, can spread rapidly among poultry flocks, and early detection is critical to prevent outbreaks. Key symptoms that indicate your chicken may be infected include sudden death without prior signs, decreased appetite, reduced egg production, nasal discharge, coughing, sneezing, swelling around the eyes, purple discoloration on wattles or combs, and neurological issues such as tremors or lack of coordination. Since these signs can resemble other poultry diseases, definitive diagnosis requires veterinary involvement and lab analysis. Recognizing how to identify bird flu in backyard chickens is essential for all poultry keepers, especially during seasonal outbreaks.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Biological Overview

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is caused by Type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild birds, particularly waterfowl like ducks and geese. While wild birds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, domestic poultry—including chickens—are highly susceptible to severe illness. The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, contaminated feces, respiratory secretions, or surfaces like feeders, waterers, and clothing.

There are two main types of avian influenza: low pathogenic (LPAI) and high pathogenic (HPAI). LPAI may cause mild respiratory issues or go unnoticed, while HPAI progresses rapidly and can result in mortality rates approaching 90–100% within 48 hours. The most concerning strains affecting poultry include H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. These viruses not only threaten flock health but also pose zoonotic risks—meaning they can occasionally infect humans, especially those in close contact with sick birds.

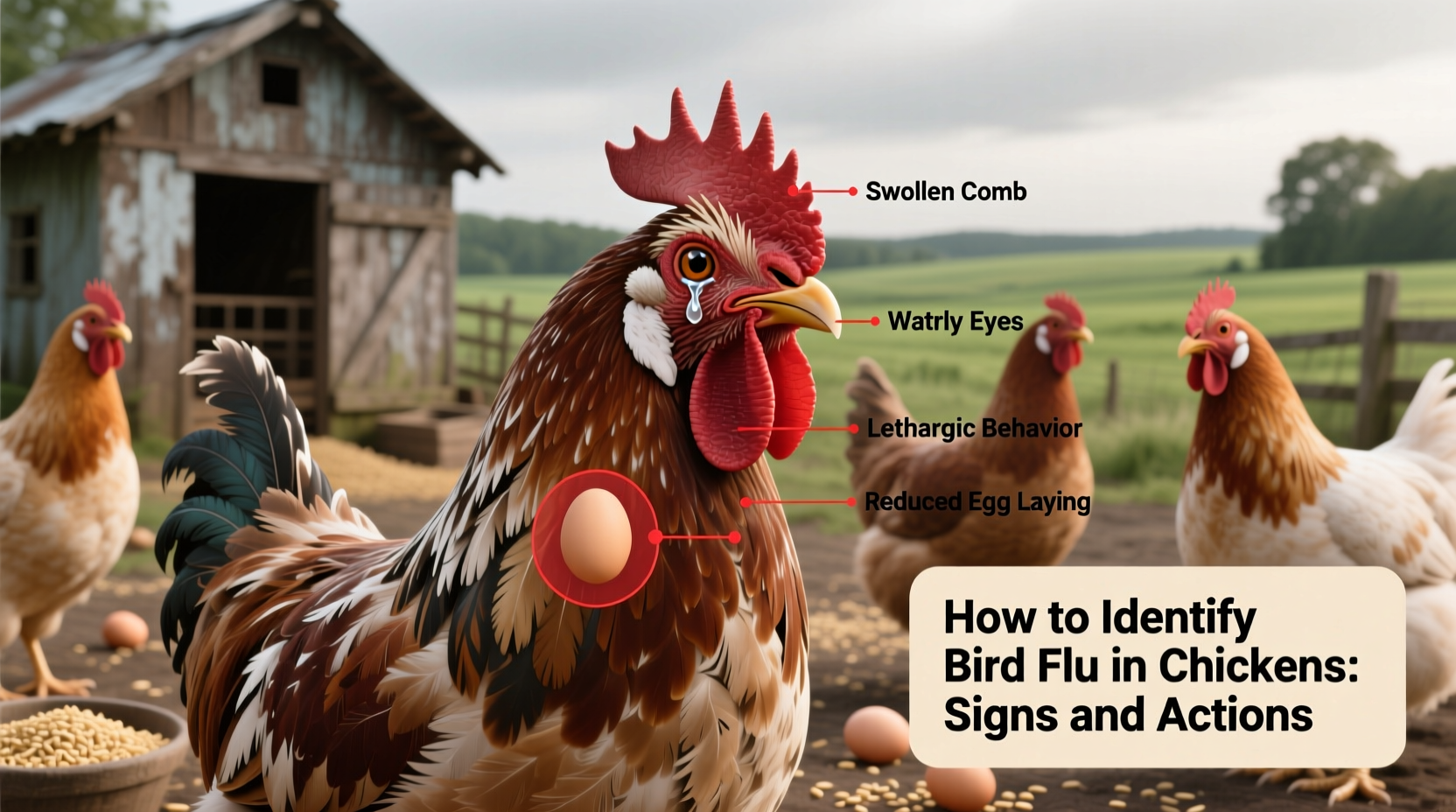

Early Warning Signs in Chickens

Detecting bird flu early can save lives and prevent widespread contamination. Chicken owners should monitor their flocks daily for any deviations from normal behavior. Common early indicators include:

- Sudden and unexplained deaths, sometimes overnight

- Drop in egg production or soft-shelled eggs

- Lethargy, huddling, or reluctance to move

- Swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, or legs

- Discharge from nostrils or mouth

- Difficulty breathing, gasping, or gurgling sounds

- Diarrhea, often greenish in color

- Neurological symptoms: tremors, twisted necks, circling, or paralysis

It's important to note that not all infected birds will display every symptom. Some may appear only mildly ill before dying suddenly. In backyard flocks, where biosecurity measures may be less rigorous, transmission can occur quickly once one bird is infected.

Differentiating Bird Flu from Other Poultry Diseases

Many poultry ailments mimic bird flu symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis without proper testing. For example:

- Newcastle disease causes similar respiratory and neurological signs.

- Fowl cholera leads to swelling and sudden death.

- Infectious bronchitis reduces egg production and causes respiratory distress.

The key difference is the speed and severity of onset. Bird flu, particularly HPAI, tends to affect multiple birds in a short timeframe. If more than 20% of your flock shows illness within 24–48 hours, suspect avian influenza immediately. Only laboratory testing can confirm the presence of the virus, so prompt reporting is crucial.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu in Your Flock

If you observe symptoms consistent with bird flu in your chickens, take immediate action:

- Isolate sick birds: Separate any showing signs from the rest of the flock using dedicated equipment and clothing.

- Stop movement: Do not transport birds, eggs, or equipment off the property.

- Contact authorities: Report suspected cases to your state veterinarian or local agricultural extension office. In the U.S., the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) oversees avian disease response.

- Collect samples: A veterinarian may collect swabs from the cloaca and trachea for PCR testing.

- Follow quarantine protocols: Premises may be placed under official quarantine until test results are confirmed.

Do not attempt home remedies or treat with antibiotics, as bird flu is viral and antibiotics are ineffective. Moreover, improper handling increases the risk of spreading the virus.

Prevention Through Biosecurity Measures

Preventing bird flu starts with strong biosecurity practices. Backyard poultry owners often underestimate risks from indirect exposure. Consider the following protective steps:

- Limit visitors: Restrict access to your coop area. Require footwear disinfection before entry.

- Control wild bird access: Cover runs with netting and avoid placing feed/water outdoors where wild birds can contaminate them.

- Clean and disinfect regularly: Use approved disinfectants like bleach solutions (1:10 dilution) on coops, feeders, and tools.

- Quarantine new birds: Keep newly acquired chickens isolated for at least 30 days and monitor for illness.

- Avoid sharing equipment: Don’t loan out cages, crates, or tools used around your flock.

- Practice personal hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly after handling birds and change clothes before visiting other flocks.

During peak migration seasons—typically fall and spring—the risk of avian influenza introduction increases significantly. Staying informed about regional outbreaks via USDA alerts or local agricultural departments is vital.

Regional Variations and Seasonal Trends

Bird flu occurrence varies by geography and season. In North America, outbreaks are most common between October and June, coinciding with wild bird migrations. Regions with high concentrations of commercial poultry, such as the Midwest U.S. or parts of Canada, experience more frequent detections. However, backyard flocks in rural and suburban areas are equally vulnerable, especially if located near wetlands or migratory flyways.

In Europe and Asia, certain countries report recurring H5N1 strains, prompting strict import controls and surveillance programs. International travelers should avoid visiting poultry farms abroad and refrain from bringing back feathers, eggs, or live birds.

Climate change and shifting migration patterns may alter future outbreak timelines. Warmer winters could extend the window of viral persistence in the environment, increasing exposure risk.

Economic and Emotional Impact on Small-Scale Farmers

For smallholders and homesteaders, losing a flock to bird flu is both economically devastating and emotionally taxing. Chickens provide food security, income from egg sales, and companionship. An outbreak may lead to mandatory depopulation, disposal costs, and long recovery periods before restocking is allowed.

Government compensation programs exist in some regions, but eligibility varies. In the U.S., indemnity payments may cover part of the loss, though processing delays are common. Understanding your local regulations and maintaining detailed flock records—including purchase dates, breed, and health logs—can streamline claims and aid epidemiological tracing.

Public Health Implications and Zoonotic Risk

While human infections with avian influenza remain rare, they do occur. Most cases involve individuals with prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected birds. Symptoms in humans range from conjunctivitis and fever to severe pneumonia. The H5N1 strain has caused over 900 human cases globally since 2003, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%, according to WHO data.

To reduce zoonotic risk:

- Wear gloves and masks when handling sick or dead birds.

- Avoid touching your face during cleanup.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly (internal temperature ≥165°F / 74°C).

- Report any human flu-like illness following bird contact to a healthcare provider.

Currently, there is no sustained human-to-human transmission of bird flu, but ongoing mutations necessitate vigilance.

Debunking Common Misconceptions

Several myths surround bird flu and backyard poultry:

- Misconception: 'Only large farms get bird flu.'

Reality: Backyard flocks account for nearly half of reported U.S. cases in recent years. - Misconception: 'Free-range chickens are safer.'

Reality: Outdoor access increases exposure to wild bird droppings. - Misconception: 'Vaccines are widely available for backyard birds.'

Reality: No USDA-approved vaccine is currently available for private use; prevention relies on biosecurity. - Misconception: 'Eating eggs or chicken causes infection.'

Reality: Proper cooking destroys the virus; transmission occurs through close contact with live/sick birds.

How Surveillance Systems Work

National and international agencies monitor avian influenza through coordinated surveillance. In the U.S., the USDA, CDC, and state departments collaborate on early detection. Wild bird sampling, live bird market testing, and mandatory reporting by veterinarians help track virus circulation.

Poultry owners play a critical role in this system. Timely reporting of suspicious deaths enables rapid containment. Some states offer free diagnostic services through land-grant universities or veterinary labs.

| Symptom | Common in Bird Flu? | Also Seen In |

|---|---|---|

| Sudden death | Yes (especially HPAI) | Fowl cholera, Marek’s disease |

| Swollen head/comb | Yes | Avian metapneumovirus, fowl pox |

| Respiratory distress | Yes | Infectious bronchitis, mycoplasma |

| Neurological signs | Yes | Newcastle disease, vitamin deficiency |

| Green diarrhea | Yes | Coccidiosis, salmonellosis |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I eat eggs from a chicken with bird flu?

No. Eggs from infected birds should not be consumed. The virus can be present in internal tissues and reproductive organs. Destroy all eggs laid in the 7 days before symptom onset.

How long does bird flu survive in the environment?

The virus can persist for up to 30 days in cool, moist conditions (like manure or water), but only 24–48 hours in dry, sunny environments. Disinfection is essential after depopulation.

Is there a home test for bird flu in chickens?

No reliable at-home tests exist. Rapid antigen kits are not approved for consumer use and may yield false results. Always rely on certified laboratories for diagnosis.

Should I cull my entire flock if one bird is infected?

Yes, in most jurisdictions. Due to extreme contagion, officials typically require depopulation of the entire premises to prevent further spread.

Where can I report a suspected case of bird flu?

In the U.S., contact your state veterinarian, local extension office, or call the USDA APHIS hotline at 1-866-536-7593. Similar agencies exist in Canada (CFIA), the UK (DEFRA), and Australia (DAFF).

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4