Bird egg fertilization occurs internally when a male bird transfers sperm to a female during mating, and the sperm unites with the ovum in the oviduct—this process is known as internal fertilization in birds. Understanding how does a bird egg get fertilized reveals not only the biological mechanics behind avian reproduction but also offers insight into nesting behaviors, breeding seasons, and successful chick development. This natural process begins well before the hard-shelled egg is laid, starting with ovulation in the female’s single functional ovary.

The Biological Process of Bird Egg Fertilization

In birds, reproduction is sexual and requires both a male and a female. Unlike mammals, most birds lack external genitalia; instead, they use a cloaca—a single opening used for excretion and reproduction—commonly referred to as "cloacal kiss" during mating. During this brief contact, the male transfers sperm from his cloaca to the female’s. The sperm then travel up the oviduct to meet the yolk (developing ovum) shortly after it’s released from the ovary.

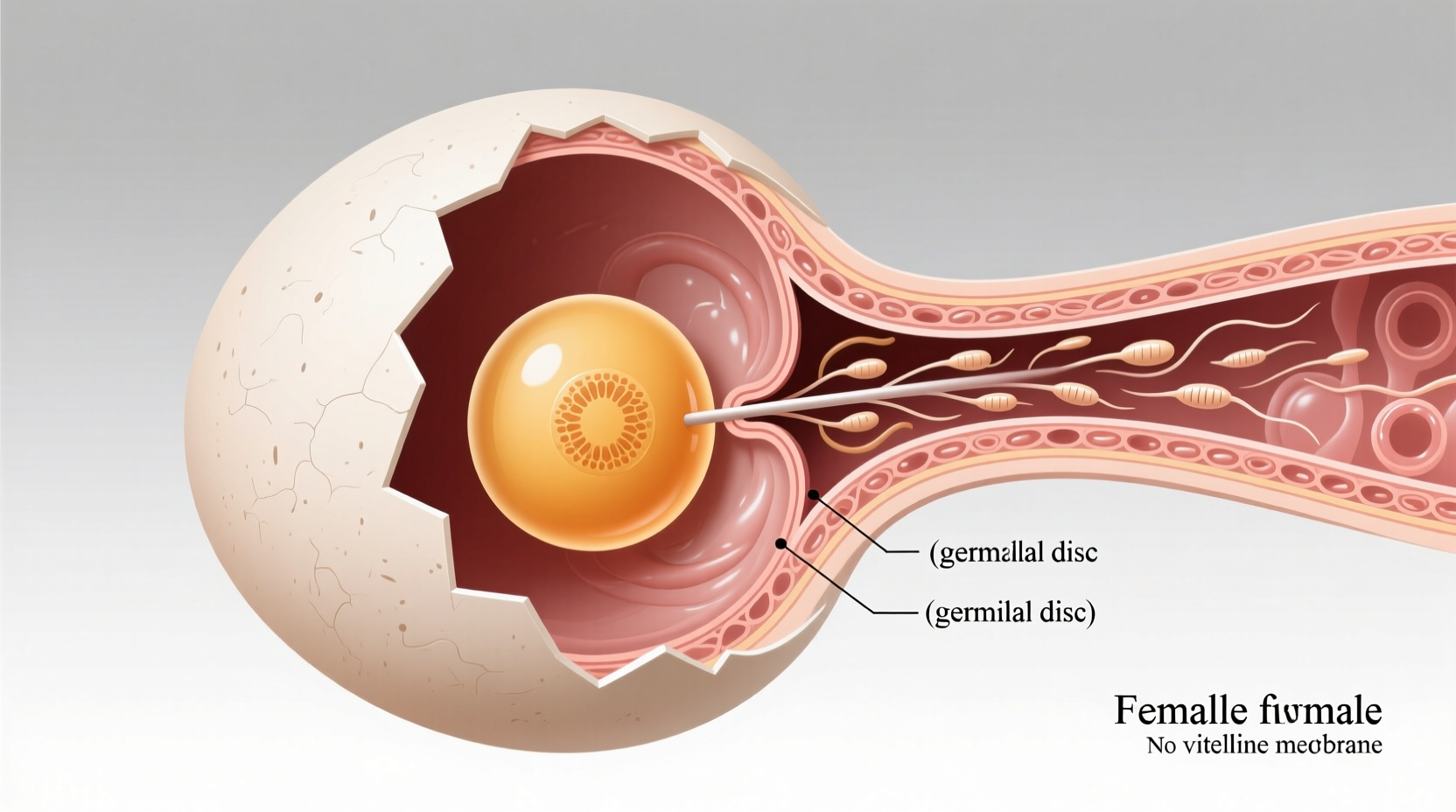

Fertilization happens in the infundibulum, the uppermost section of the oviduct, within about 15 to 30 minutes after ovulation. If sperm are present, they penetrate the outer layers of the yolk, and one fuses with the nucleus of the ovum to form a zygote. From that moment, cell division begins, marking the start of embryonic development—even before the egg is fully formed or laid.

After fertilization, the yolk moves down the oviduct where successive layers are added: the albumen (egg white), several membranes, and finally the calcified shell in the uterus (also called the shell gland). This entire process takes approximately 24 hours in most bird species. Therefore, by the time a bird lays an egg, embryonic development may already be underway if the egg was fertilized.

Differences Between Fertilized and Unfertilized Bird Eggs

Many people wonder whether all bird eggs are fertilized. The answer is no. Female birds can lay eggs without mating—just like chickens in commercial farms produce unfertilized eggs daily. These unfertilized eggs will never develop into chicks because there is no genetic contribution from a male.

A fertilized egg contains a small white bullseye-like structure on the yolk called the blastodisc (which becomes the blastoderm after fertilization), visible upon cracking open the egg. In contrast, unfertilized eggs have a more uniform, pale spot that doesn’t divide. However, visual inspection alone isn’t always reliable, especially after several days.

For those interested in hatching chicks, only fertilized eggs incubated under proper temperature and humidity conditions will develop. Backyard poultry keepers often pair roosters with hens to ensure fertility, while pet bird owners may observe mating behaviors in parrots or finches leading to fertile clutches.

Mating Behavior and Timing in Birds

The timing of mating relative to ovulation is crucial for successful fertilization. Most female birds ovulate just after laying an egg, meaning they typically mate the day before or the same day an egg is produced. Some species, such as pigeons and doves, can store sperm in specialized tubules in the oviduct for up to several weeks, increasing chances of fertilization even if mating occurred days prior.

Birds often exhibit courtship rituals before mating, including singing, dancing, feather displays, or feeding offerings. These behaviors strengthen pair bonds and signal readiness to reproduce. For example, male Northern Cardinals bring food to females as part of courtship, while male Peacocks display their elaborate tail feathers to attract mates.

Mating itself is usually quick, lasting only seconds due to the cloacal kiss mechanism. There is no intromission as seen in mammals. Despite its brevity, successful sperm transfer ensures that multiple eggs in a clutch can be fertilized from a single mating event, particularly in species that lay several eggs over consecutive days.

Species-Specific Variations in Fertilization and Reproduction

While the general mechanism of internal fertilization holds across bird species, reproductive strategies vary widely. Below is a comparison of different avian groups:

| Species | Mating System | Sperm Storage? | Eggs per Clutch | Fertilization Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) | Polygynous | Yes (up to 2 weeks) | 4–6 | Within 24 hours post-ovulation |

| House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) | Monogamous | Limited | 3–6 | Same day as ovulation |

| Barn Owl (Tyto alba) | Monogamous | Moderate | 4–7 | 12–24 hours pre-laying |

| Hummingbird (various) | Polyandrous | Yes (several days) | 2 | Shortly after ovulation |

| Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) | Serially monogamous | Yes | 5–15 | Within 30 minutes of ovulation |

These variations reflect adaptations to ecological niches, predation pressures, and parental care requirements. For instance, precocial birds like ducks and chickens tend to have larger clutches and shorter incubation periods, whereas altricial birds like songbirds invest more energy in fewer offspring requiring extended care.

Environmental and Seasonal Influences on Fertilization

Bird reproduction is highly seasonal, influenced primarily by photoperiod (day length), temperature, and food availability. As daylight increases in spring, hormonal changes trigger gonadal development in both males and females. Testosterone levels rise in males, prompting territorial behavior and mating calls, while estrogen surges in females stimulate yolk production and oviduct growth.

In tropical regions, where seasons are less pronounced, some birds breed year-round or synchronize with rainy seasons when insect populations peak. Captive birds, however, may breed out of season due to artificial lighting and consistent food supply—important considerations for breeders aiming to control fertility timing.

Climate change is also affecting avian breeding cycles. Studies show that many temperate zone birds are initiating nesting earlier than in previous decades, potentially creating mismatches between chick hatching and peak food abundance—an issue that could indirectly impact fertilization success through reduced adult condition.

Observing Fertilization in Wild and Captive Birds

For birdwatchers and researchers, identifying signs of active breeding and potential fertilization involves observing behavioral cues. Look for:

- Courtship displays (e.g., sky-pointing in geese, bowing in penguins)

- Nest-building activity

- Cloacal swelling in females

- Increased aggression or territoriality in males

- Feeding behavior between mates (courtship feeding)

In captivity, aviculturists can assess fertility using candling—the practice of shining a bright light through an eggshell to detect blood vessels or embryonic development, typically visible after 3–5 days of incubation. Eggs that remain clear beyond this point were likely unfertilized or failed to develop.

It's important to note that not all mated pairs successfully fertilize eggs. Factors such as age, health, stress, poor nutrition, or infertility can reduce reproductive success. In endangered species conservation programs, artificial insemination is sometimes used to maximize genetic diversity and improve fertilization rates.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Egg Fertilization

Several myths persist about how bird eggs become fertilized:

- Myth: All eggs laid by birds are fertilized.

Fact: Only eggs laid after mating with a male have the potential to be fertilized. - Myth: You can tell if an egg is fertilized just by looking at the shell.

Fact: Shell appearance doesn't indicate fertility; internal examination or candling is required. - Myth: Birds need to mate every time they lay an egg.

Fact: Due to sperm storage, one mating can fertilize multiple eggs over several days. - Myth: Refrigerating a fertilized egg stops development permanently.

Fact: Cooling pauses cell division, but if returned to warmth, development may resume—unless the embryo has died.

Practical Tips for Bird Owners and Researchers

If you're keeping pet birds or studying wild populations, consider these best practices:

- Monitor mating behavior: Record interactions to estimate fertilization likelihood.

- Provide optimal nutrition: Calcium, protein, and vitamins A and E support healthy gamete production.

- Use candling tools: Check for embryonic development around day 3–5 of incubation.

- Control environmental factors: Maintain appropriate light cycles and temperatures to encourage natural breeding rhythms.

- Consult avian veterinarians: For persistent infertility issues, professional evaluation is essential.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How soon after mating does a bird lay a fertilized egg?

- A female bird typically lays her first fertilized egg within 24 to 48 hours after successful mating, depending on species and ovulation cycle.

- Can a bird lay fertilized eggs without a male present?

- No, a male must mate with the female for fertilization to occur. However, stored sperm can allow delayed fertilization over several days or weeks.

- Do all birds reproduce the same way?

- While all birds use internal fertilization via cloacal transfer, mating systems, clutch sizes, incubation periods, and parental roles vary significantly among species.

- Is it safe to eat fertilized bird eggs?

- Yes, fertilized eggs are safe to eat if collected and refrigerated promptly. No embryonic development occurs under cold storage.

- How can I tell if a wild bird’s egg is fertilized?

- Without candling equipment or incubation, it's nearly impossible to determine fertility in the field. Disturbing wild nests is discouraged and often illegal.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4