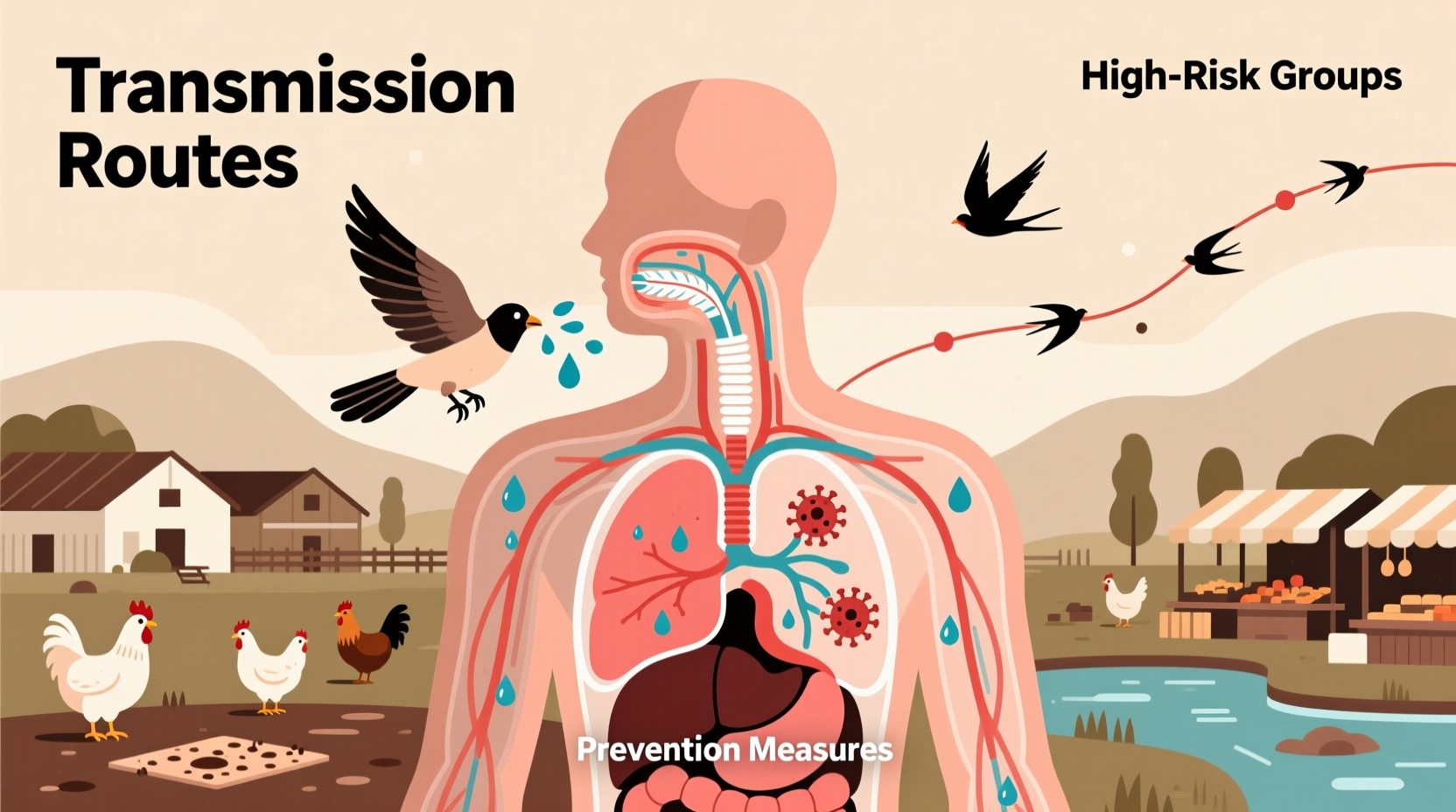

Humans can contract bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids, such as saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. The most common way a human gets bird flu is through close interaction with live or dead poultry that are infected with the virus, especially in backyard flocks or live bird markets. This transmission route—how does a human get bird flu—is particularly relevant in rural areas of Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe where people live in close proximity to domesticated birds. While rare, human-to-human transmission has occurred in isolated cases, but sustained spread between people remains extremely limited.

Understanding Bird Flu: What It Is and How It Spreads

Bird flu is caused by influenza A viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds, such as ducks and geese. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers. However, when the virus spreads to domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys, it can cause severe illness and high mortality rates. There are numerous subtypes of avian influenza, classified by surface proteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), including H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6—all of which have been associated with human infections.

The primary mode of transmission from birds to humans involves exposure to contaminated environments. For example, cleaning coops, handling sick birds, or slaughtering infected poultry increases risk. Inhalation of airborne particles from dried bird droppings or respiratory secretions in enclosed spaces can also lead to infection. Although consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs does not transmit the virus, cross-contamination during food preparation poses a potential hazard if hygiene practices are inadequate.

Historical Outbreaks and Global Impact

The first documented case of human infection with avian influenza occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, involving the H5N1 strain. Since then, sporadic outbreaks have emerged across multiple continents. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 900 human cases of H5N1 were reported between 2003 and 2024, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. More recently, the H5N1 virus has undergone genetic evolution, leading to increased spread among wild bird populations and unprecedented outbreaks in both commercial and backyard poultry farms worldwide.

In 2022 and 2023, highly pathogenic H5N1 strains triggered mass culling events in the United States, Europe, and parts of Asia. In the U.S., millions of birds were affected, prompting federal agencies like the CDC and USDA to enhance surveillance and biosecurity protocols. Notably, these outbreaks coincided with an increase in confirmed human cases linked to occupational exposure—farmers, veterinarians, and cullers being at highest risk.

Risk Factors and High-Risk Populations

While anyone exposed to infected birds may be at risk, certain groups face greater vulnerability:

- Farm workers and poultry handlers

- Veterinarians and animal health inspectors

- Individuals involved in live bird markets

- Backyard flock owners

- Travelers visiting regions experiencing active outbreaks

Children and immunocompromised individuals may experience more severe outcomes if infected. Additionally, cultural practices such as cockfighting or using poultry waste as fertilizer can amplify exposure risks in some communities.

It's important to note that urban dwellers who do not interact directly with birds remain at very low risk. Most confirmed human cases occur in countries where backyard farming is common and access to protective equipment is limited.

Symptoms and Diagnosis in Humans

When a person contracts bird flu, symptoms typically appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure. Early signs resemble seasonal influenza, including:

- Fever (often high)

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Headache

However, the disease can rapidly progress to lower respiratory tract complications such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure. Gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea have also been reported, particularly with H7N9 infections.

Diagnosis requires laboratory testing, usually via reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swabs). Blood tests may detect antibodies over time. Rapid antigen tests used for seasonal flu are not reliable for identifying avian influenza, so clinical suspicion based on travel history and exposure is critical.

Prevention Strategies and Public Health Measures

Preventing human infection hinges on minimizing contact with potentially infected birds and implementing strict biosecurity measures. Key recommendations include:

- Avoiding live bird markets in outbreak zones

- Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) when handling birds

- Practicing thorough hand hygiene after any bird contact

- Ensuring poultry and eggs are fully cooked (internal temperature ≥74°C / 165°F)

- Reporting sick or dead birds to local authorities

Public health agencies monitor migratory bird patterns and conduct routine surveillance in poultry farms. Vaccination of poultry is practiced in some countries, though no universal vaccine exists due to viral diversity. Human vaccines for H5N1 and H7N9 are available in limited quantities for emergency use but are not part of routine immunization programs.

Treatment Options and Medical Response

If bird flu is suspected, prompt antiviral treatment is essential. Neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir (Rapivab) are recommended, ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset. These drugs can reduce severity and duration of illness, even in cases caused by resistant strains.

Hospitalized patients often require intensive supportive care, including mechanical ventilation. Corticosteroids and antibiotics may be used to manage secondary infections, though evidence supporting steroid use remains inconclusive. Experimental therapies, including monoclonal antibodies and convalescent plasma, are under investigation.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several misconceptions persist about how humans get bird flu:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs causes bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized egg products pose no risk. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been observed; most cases stem from animal contact. - Myth: All bird species are equally dangerous.

Fact: Wild waterfowl often carry the virus asymptomatically, while domestic poultry show high mortality. - Myth: Pet birds cannot get or spread bird flu.

Fact: Though rare, pet parrots and cage birds can become infected if exposed to wild birds or contaminated materials.

Dispelling misinformation helps prevent unnecessary panic and supports effective public health responses.

Regional Differences in Risk and Reporting

The likelihood of contracting bird flu varies significantly by region. Countries with frequent outbreaks—such as China, Vietnam, Egypt, and Indonesia—have established national response plans, including rapid culling, movement restrictions, and compensation schemes for farmers. In contrast, North America and Western Europe report fewer human cases, largely due to stronger veterinary infrastructure and biosecurity standards.

However, climate change and shifting migration routes are altering the geographic distribution of infected birds. In 2024, H5N1 was detected in wild birds across all 50 U.S. states, raising concerns about spillover into new ecosystems. Travelers should consult the CDC’s travel health notices before visiting regions with active avian influenza activity.

| Region | Common Subtypes | Human Cases (2003–2024) | Primary Exposure Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| East/Southeast Asia | H5N1, H7N9 | ~700 | Live bird markets, backyard flocks |

| Egypt | H5N1 | ~350 | Poultry farming, home slaughter |

| North America | H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b) | 5 | Occupational exposure (culling) |

| Europe | H5N1, H5N8 | 12 | Wild bird contact, farm work |

What to Do If You Suspect Exposure

If you’ve had close contact with sick or dead birds and develop flu-like symptoms within 10 days, take immediate action:

- Isolate yourself from others

- Contact your healthcare provider or local health department

- Mention your bird exposure clearly

- Follow guidance for testing and quarantine

Do not attempt to treat yourself with leftover antivirals or antibiotics. Only a medical professional can determine appropriate management.

Future Outlook and Pandemic Preparedness

Bird flu remains a significant zoonotic threat due to its high lethality and potential for mutation. Scientists closely monitor the virus for changes that could enable efficient human-to-human transmission—a scenario that might trigger a pandemic. Ongoing research focuses on universal influenza vaccines, improved diagnostics, and early warning systems using genomic sequencing and satellite tracking of bird migrations.

Global cooperation through organizations like WHO, FAO, and OIE is vital for controlling outbreaks at the source. Strengthening veterinary services in low-income countries, promoting safe farming practices, and enhancing public awareness are key components of long-term prevention.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can I get bird flu from watching birds in my backyard?

No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Infection requires direct contact with infected birds or their excretions. - Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

Limited stockpiles of pre-pandemic vaccines exist for H5N1 and H7N9, but they are not commercially available to the general public. - How contagious is bird flu between humans?

Very low. Rare instances of human-to-human transmission have occurred among close family members caring for ill patients, but no sustained community spread has been documented. - Should I stop feeding wild birds?

If there are no local advisories, feeding wild birds is generally safe. Avoid touching birds or cleaning feeders without gloves, and sanitize regularly. - Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu?

Yes, wild migratory birds—especially waterfowl—are natural reservoirs and play a major role in global dissemination of avian influenza viruses.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4