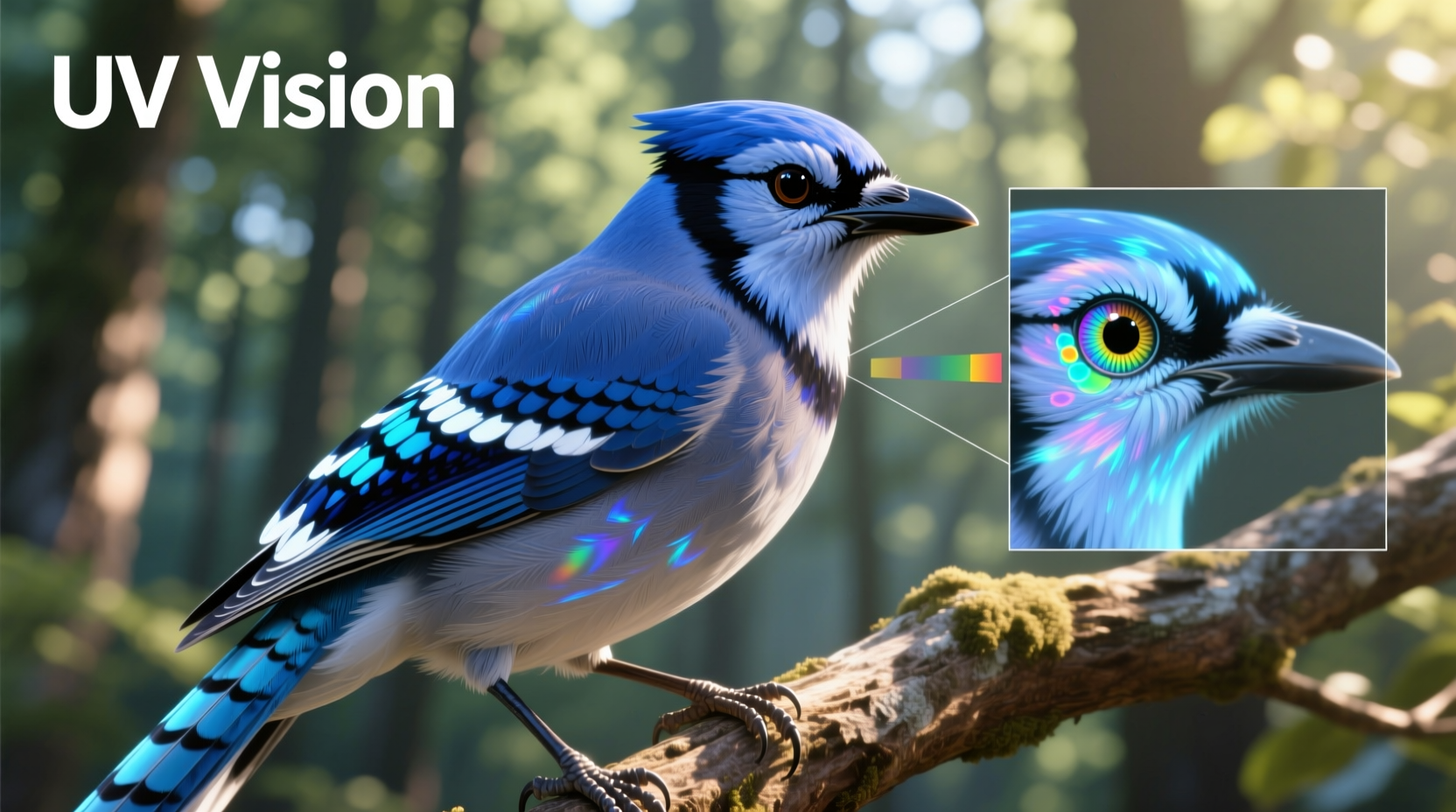

Birds see the world in a way that is fundamentally different from humans, thanks to unique adaptations in their eyes and visual processing systems. How does birds see? They possess tetrachromatic vision, meaning they have four types of cone cells in their retinas—compared to our three—allowing them to perceive ultraviolet (UV) light, a spectrum invisible to human eyes. This enhanced visual capability enables birds to detect subtle patterns on feathers, locate food sources like UV-reflecting berries, and navigate using polarized light during migration. Understanding how birds see reveals not only their biological sophistication but also deepens our appreciation for avian behavior and ecology.

The Science Behind Avian Vision

At the core of how birds see lies the structure of their eyes and the density of photoreceptor cells. Most birds have large eyes relative to their head size, which enhances light gathering and image resolution. Their eyes are tubular rather than spherical, providing greater focal length and sharper vision. Unlike mammals, birds have a pecten—a fold projecting into the vitreous humor—that nourishes the retina and reduces shadow formation, improving clarity.

The key difference between human and avian vision lies in color perception. Humans are trichromats: we have red, green, and blue cones. Birds, however, are tetrachromats, with an additional cone type sensitive to ultraviolet wavelengths. This allows them to distinguish colors we can’t even imagine. For example, many bird species appear sexually monomorphic to us, but under UV light, males often display bright plumage patterns invisible without specialized vision.

Another critical feature is the high density of ganglion cells in the retina. These cells transmit visual information to the brain. In raptors like eagles and hawks, this density is exceptionally high, contributing to their remarkable visual acuity—up to eight times sharper than humans. A golden eagle can spot a rabbit from over two miles away, thanks to both eye structure and neural processing efficiency.

Visual Fields and Depth Perception

How birds see also depends on eye placement, which varies by species and relates directly to ecological niche. Predatory birds such as owls and eagles have forward-facing eyes, giving them significant binocular overlap—sometimes exceeding 60 degrees. This provides excellent depth perception, crucial for judging distances when diving at high speeds or striking prey.

In contrast, prey species like pigeons and ducks have eyes positioned more laterally on their heads. This gives them nearly 360-degree panoramic vision, allowing them to detect predators approaching from almost any direction. However, this wide field comes at the cost of reduced binocular vision and less accurate depth judgment.

Some birds, like woodcocks, take peripheral vision to extremes. They can see behind themselves without turning their heads due to rearward-positioned eyes. Meanwhile, kingfishers and other diving birds have evolved dual foveae—one for aerial viewing and one for underwater focus—enabling sharp vision both above and below water surfaces.

Ultraviolet and Polarized Light Detection

One of the most fascinating aspects of how birds see involves their ability to detect ultraviolet (UV) and polarized light. UV sensitivity plays a vital role in mate selection. Studies show that female zebra finches prefer males whose cheek patches reflect more UV light, indicating health and genetic fitness. Similarly, European starlings use UV cues to assess plumage quality during courtship displays.

UV vision also aids in foraging. Many fruits, seeds, and insects reflect UV light, making them stand out against foliage. Bees and some beetles leave UV-visible scent trails, which insectivorous birds may exploit. Even nectar guides on flowers—patterns visible only in UV—are detectable by hummingbirds and sunbirds, guiding them to energy-rich rewards.

Polarized light detection helps birds orient during long-distance migrations. By sensing the angle of polarized sunlight scattered in the atmosphere, birds like swallows and warblers can maintain course even under overcast skies. This celestial navigation system works in conjunction with magnetic field detection, forming a multimodal guidance network embedded in their sensory biology.

Nocturnal vs. Diurnal Vision Adaptations

Different lighting conditions demand specialized visual adaptations. Owls, as nocturnal hunters, have extremely large corneas and pupils that maximize light intake. Their retinas are dominated by rod cells—responsible for low-light vision—with relatively fewer cones. Despite this, some owl species retain limited color vision, suggesting evolutionary trade-offs rather than complete loss of spectral discrimination.

Diurnal raptors, on the other hand, balance acute daylight vision with motion detection. Falcons, for instance, have a horizontal streak of high ganglion cell density across the retina, ideal for tracking fast-moving prey across open landscapes. This adaptation supports their high-speed dives, where split-second decisions depend on precise visual input.

Nightjars and nighthawks exhibit intermediate traits, being crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk). Their eyes blend features of both day and night specialists, enabling function in dim light while retaining sufficient color discrimination for identifying insects in twilight hours.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Vision

Beyond biology, how birds see has inspired myths, metaphors, and spiritual symbolism across cultures. In Native American traditions, the eagle’s far-reaching gaze symbolizes divine insight and connection to the Creator. Its ability to soar high and see clearly represents wisdom, foresight, and moral clarity. Similarly, in ancient Egyptian mythology, Horus—the falcon-headed god—embodied royal power and omniscience, his eyes representing the sun and moon.

In literature and philosophy, “a bird’s-eye view” denotes objectivity and comprehensive understanding. The phrase reflects admiration for avian visual superiority and metaphorically encourages people to rise above immediate circumstances to gain broader perspective. Modern psychology sometimes uses avian metaphors to describe mindfulness—observing thoughts like a bird watching clouds pass overhead, detached yet aware.

These cultural narratives reinforce scientific truths: birds do see more than we do, not just in spectrum but in scope. Recognizing this fosters respect for non-human ways of perceiving reality and challenges anthropocentric assumptions about sensory experience.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers

Understanding how birds see can dramatically improve birdwatching success. First, avoid wearing white or UV-bright clothing. Many detergents contain optical brighteners that reflect UV light, making humans highly visible to birds even in camouflage gear. Opt for muted, non-fluorescent fabrics to reduce detection.

Use UV-blocking sunscreen cautiously; some ingredients may emit UV signatures. Instead, rely on physical barriers like hats and nets. When photographing birds, consider using UV filters to simulate what humans see versus what birds might perceive. Specialized cameras with UV sensitivity can reveal hidden plumage patterns and behavioral cues.

Position yourself carefully based on species’ visual fields. Approach songbirds from the front or slightly above, avoiding sudden lateral movements they’re primed to notice. With raptors, move slowly and maintain steady eye contact—they interpret erratic motion as threat signals.

Timing matters too. Early morning and late afternoon offer softer light and increased bird activity. During these periods, polarization effects are strongest, potentially influencing bird behavior. Observing flight paths at sunrise may reveal navigational strategies tied to sky polarization patterns.

| Bird Species | Visual Acuity (Relative to Humans) | Color Vision | Field of View | Special Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Eagle | 8x sharper | Tetrachromatic (incl. UV) | ~150° binocular | Dual fovea, high ganglion density |

| Barn Owl | Moderate | Limited color | Frontal binocular (~70°) | Large pupils, rod-dominated retina |

| Rock Pigeon | Slightly better | Tetrachromatic | Nearly 360° | Lateral eye placement, rapid head stabilization |

| Anna’s Hummingbird | High motion sensitivity | Full tetrachromatic | Moderate binocular | UV-sensitive plumage, rapid neural processing |

| European Starling | Average | Strong UV perception | Wide lateral view | Iridescent feathers visible in UV |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Vision

Despite growing awareness, several myths persist about how birds see. One common belief is that all birds have poor night vision. While true for diurnal species, many birds—including owls, nightjars, and some seabirds—are superbly adapted to darkness. Another misconception is that birds cannot recognize individual humans. Research shows crows, parrots, and gulls can identify human faces and remember hostile individuals for years.

Some assume birds see in slow motion. While not literally true, their flicker fusion rate—the speed at which images blend into continuous motion—is much higher than ours. This means they perceive rapid events in finer temporal detail, akin to watching video at higher frame rates. That’s why sudden gestures startle them more easily.

Finally, there's a myth that birds are distracted solely by color. In reality, movement, shape, contrast, and context matter equally. A motionless red object may go unnoticed, while a small moving silhouette triggers instant alertness.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds see colors humans can't? Yes, birds can see ultraviolet light, which expands their color spectrum beyond human capabilities.

- Do all birds have the same type of vision? No, visual systems vary widely depending on species, habitat, and behavior—e.g., raptors vs. nocturnal owls.

- How does UV vision affect mating? UV-reflective plumage helps birds assess mate quality, influencing partner selection in many species.

- Why do birds react to sudden movements? Their high flicker fusion rate makes them extremely sensitive to motion, enhancing predator detection.

- Can I observe UV patterns on birds? Not with naked eyes, but UV photography equipment can reveal hidden feather markings used in communication.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4