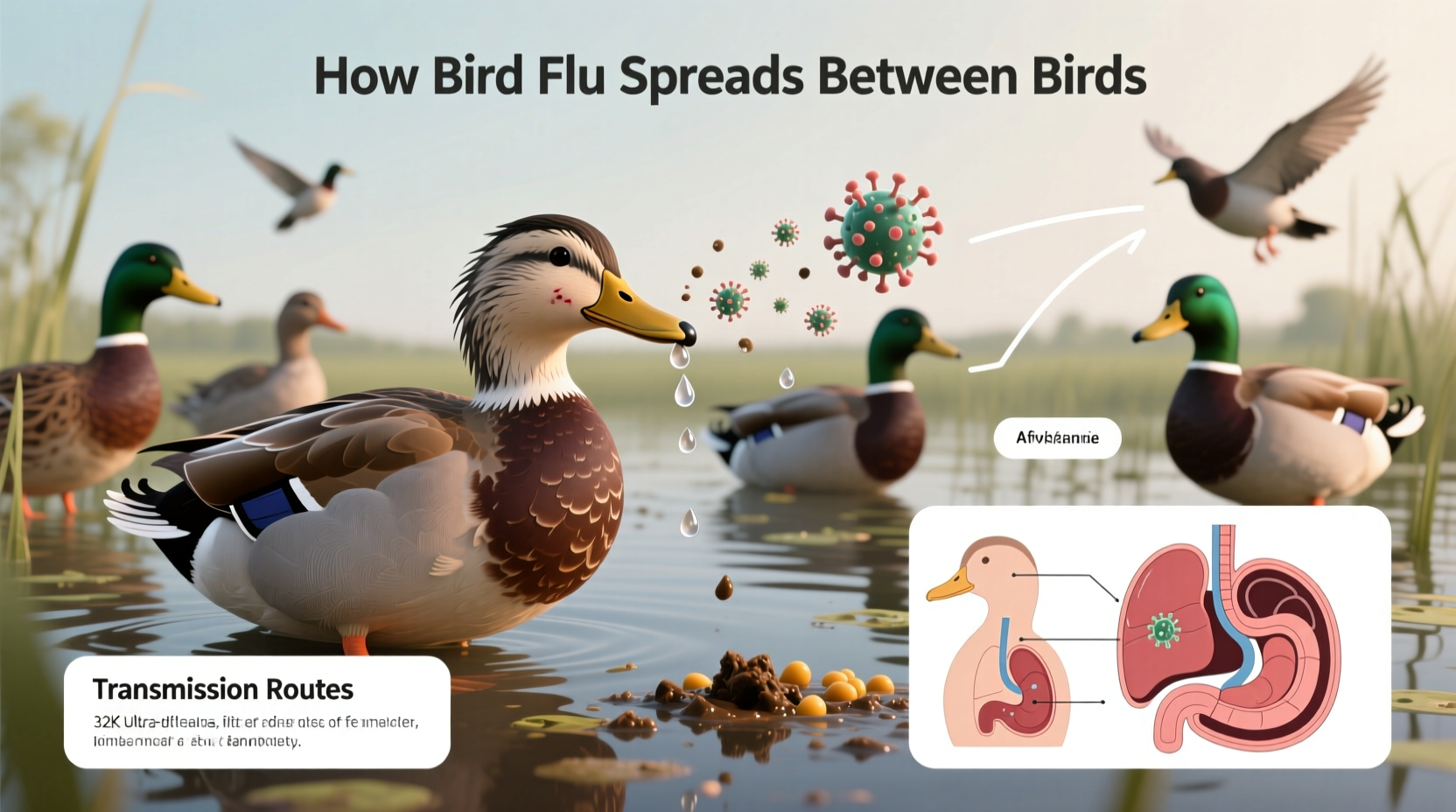

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is primarily transmitted between birds through direct contact with infected birds' respiratory secretions, saliva, and feces. One of the most common ways bird flu spreads among bird populations is via contaminated water sources, especially in wetlands where migratory and domestic birds congregate. This natural transmission pathway—how is bird flu transmitted between birds—often involves the shedding of the virus in high quantities through droppings, allowing rapid infection across flocks, particularly in dense populations such as poultry farms or crowded roosting areas.

Understanding Avian Influenza: A Biological Overview

Avian influenza is caused by Type A influenza viruses, which are categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are numerous subtypes, but H5N1 and H7N9 are among the most pathogenic in birds. These viruses naturally circulate in wild aquatic birds like ducks, geese, and shorebirds, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. This asymptomatic carriage plays a critical role in the silent spread of bird flu across continents.

The virus replicates primarily in the respiratory and digestive tracts of birds. As infected birds exhale, cough, or defecate, they release viral particles into the environment. The stability of the virus in cool, moist conditions—such as in pond water or damp soil—enhances its persistence and increases transmission risk. In fact, studies show that the H5N1 virus can remain infectious in water for up to four days at 22°C and over 30 days at 0°C, making cold-season transmission especially concerning.

Direct and Indirect Transmission Pathways

Transmission of bird flu occurs through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct transmission happens when healthy birds come into physical contact with infected individuals. This is common in commercial poultry operations where birds are housed in close proximity, enabling rapid spread once one bird becomes infected.

Indirect transmission is equally significant and often more difficult to control. Key vectors include:

- Contaminated water sources

- Fomites (objects or materials likely to carry infection, such as feed bins, cages, boots, or equipment)

- Aerosols in enclosed spaces like barns

- Predatory or scavenger birds that feed on infected carcasses

- Insects or rodents that move between infected and healthy flocks

For example, a farmer who visits an infected farm and then enters a clean poultry house without changing clothes or disinfecting footwear can inadvertently introduce the virus. This highlights the importance of biosecurity protocols in preventing outbreaks.

The Role of Migratory Birds in Spreading Bird Flu

Migratory birds are central to the global dissemination of avian influenza. Each year, millions of waterfowl travel along established flyways—such as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways in North America—crossing international borders and mixing with local bird populations. During migration, these birds stop at shared wetlands, lakes, and marshes, creating hotspots for inter-species transmission.

Research indicates that low-pathogenic strains of avian flu are commonly found in migrating ducks and shorebirds. While these strains may not cause severe illness in wild birds, they can mutate into highly pathogenic forms when introduced into susceptible domestic poultry populations. For instance, the widespread H5N1 outbreaks in 2022 and 2023 were linked to movements of infected wild birds into agricultural regions across Europe, Asia, and North America.

Climate change may be exacerbating this issue by altering migration patterns, extending the duration birds spend in certain regions, and increasing overlap between wild and domestic species. Warmer winters also allow the virus to persist longer in the environment, raising transmission potential.

Domestic Poultry and Amplification of Outbreaks

While wild birds serve as reservoirs, domestic poultry—especially chickens, turkeys, and quail—are highly vulnerable to severe disease from bird flu. Once introduced into a commercial flock, the virus can spread rapidly due to high stocking densities and shared ventilation systems. An outbreak can result in near-100% mortality in unvaccinated flocks within days.

The economic and food security implications are substantial. In the United States alone, the 2022–2023 bird flu outbreak led to the depopulation of over 58 million poultry, affecting egg and turkey meat supplies. Similar impacts were seen in Canada, the UK, and several Asian countries.

Backyard flocks are also at risk, particularly if they have outdoor access or share space with wild birds. Many backyard owners underestimate the risk, failing to implement basic biosecurity measures like netting enclosures or isolating new birds before integration.

Environmental Persistence and Fomite Transmission

One of the most insidious aspects of how bird flu spreads between birds is its ability to survive in the environment. The virus can remain viable on surfaces such as wood, metal, and plastic for days to weeks under favorable conditions. This environmental persistence means that even after an infected flock is removed, the premises can still pose a contamination risk.

Water is a particularly efficient medium for transmission. Ducks and other waterfowl often swim in communal ponds where the virus concentrates in the water column. Other birds drinking from or bathing in the same water can easily ingest or inhale the virus. Even dried fecal matter can become airborne as dust, leading to inhalation-based infections.

| Transmission Route | Likelihood in Wild Birds | Likelihood in Domestic Birds | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct contact | Moderate | High | Isolate sick birds; reduce flock density |

| Contaminated water | High | High | Use clean, covered water sources |

| Fomites (equipment, clothing) | Low | Very High | Disinfect gear; practice strict biosecurity |

| Airborne (aerosols) | Low | Moderate | Improve ventilation; avoid overcrowding |

| Carcass scavenging | Moderate | Moderate | Dispose of dead birds safely; secure waste |

Human-Mediated Spread and Biosecurity Failures

Humans play a surprisingly large role in the transmission dynamics of bird flu. Movement of live birds, used poultry crates, manure, and even feathers can transport the virus across regions. Live bird markets, where birds from multiple sources are mixed, are notorious amplifiers of infection.

Additionally, inadequate cleaning and disinfection procedures on farms increase the risk of reintroduction after an outbreak. Common oversights include using ineffective disinfectants (e.g., quaternary ammonium compounds, which are less effective against enveloped viruses like influenza), skipping downtime between flocks, and failing to quarantine new birds.

To mitigate these risks, farmers and hobbyists should adopt strict biosecurity protocols:

- Limit visitors to poultry areas

- Require dedicated footwear and clothing for bird handlers

- Disinfect vehicles and equipment entering the premises

- Source birds only from certified disease-free suppliers

- Monitor flocks daily for signs of illness (lethargy, decreased egg production, nasal discharge)

Symptoms and Detection in Birds

Recognizing early signs of bird flu is crucial for containment. In domestic birds, symptoms may include:

- Sudden death without prior signs

- Swelling of the head, eyelids, and comb

- Purple discoloration of wattles and legs

- Respiratory distress (coughing, sneezing)

- Decreased food and water intake

- Drop in egg production or soft-shelled eggs

Wild birds may display neurological signs such as lack of coordination or inability to fly. However, many infected wild birds show no symptoms, making surveillance challenging.

Rapid diagnostic tests, including PCR and antigen detection kits, are available through veterinary laboratories. If bird flu is suspected, authorities must be notified immediately, as it is a reportable disease in most countries.

Prevention and Control Measures

Preventing bird flu transmission requires a multi-layered approach:

- Vaccination: While vaccines exist for certain strains (e.g., H5 and H7), they are not universally used due to concerns about masking infection and interfering with trade. Vaccination is typically reserved for high-risk areas during outbreaks.

- Surveillance: Regular testing of wild bird populations and sentinel flocks helps detect the virus early. National programs, such as the USDA's Wild Bird Surveillance Program, monitor key species and locations.

- Quarantine and Culling: Infected flocks are usually depopulated to prevent further spread. Strict quarantine zones are established around affected areas.

- Habitat Management: Reducing overlap between wild and domestic birds—for example, by covering outdoor runs or eliminating standing water—can lower exposure risk.

Public Health Implications

Although bird flu primarily affects avian species, some strains can infect humans, usually through close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. The H5N1 and H7N9 subtypes have caused sporadic human cases, with high fatality rates. However, sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented, limiting pandemic risk—at least for now.

Consumers should know that properly cooked poultry and eggs do not transmit the virus. The World Health Organization recommends cooking meat to an internal temperature of 70°C (158°F) to ensure safety.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how bird flu spreads:

- Myth: Only domestic birds get bird flu.

Fact: Wild birds, especially waterfowl, are natural carriers. - Myth: The virus spreads easily through the air over long distances.

Fact: While aerosols can transmit the virus in enclosed spaces, long-range airborne spread is rare. - Myth: Feeding wild birds causes bird flu outbreaks.

Fact: Bird feeders are not major transmission points unless contaminated by sick birds. Regular cleaning reduces risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can pet birds get bird flu?

- Yes, especially if exposed to wild birds or contaminated materials. Indoor housing and hygiene reduce risk.

- How long does bird flu last in the environment?

- The virus can survive in water for up to 30 days in cold conditions and on surfaces for several days.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in poultry?

- Yes, but it's used selectively due to regulatory and trade implications.

- Can humans catch bird flu from eating eggs?

- No, if eggs are properly cooked. The virus is destroyed by heat.

- What should I do if I find a dead wild bird?

- Do not touch it. Report it to local wildlife or agricultural authorities for safe collection and testing.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4