Bird flu, or avian influenza, is primarily transmitted through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily secretions, including saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. A key transmission pathway involves the spread of bird flu through contaminated water sources, especially in wetlands where migratory birds congregate. The virus can also survive on surfaces such as cages, feeders, and clothing, enabling indirect transmission when humans or other animals come into contact with these materials. Wild waterfowl, particularly ducks and geese, often carry the virus asymptomatically and spread it during migration, introducing avian influenza to new regions and domestic poultry populations.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Virus Types

Avian influenza is caused by Type A influenza viruses, which are categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but the most concerning for both birds and public health are H5 and H7 strains. High-pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI), such as H5N1, can cause rapid and severe outbreaks in poultry, with mortality rates approaching 90–100% in unvaccinated flocks.

The virus originated in wild aquatic birds, which serve as natural reservoirs. These birds have co-evolved with low-pathogenic strains, allowing them to carry and shed the virus without showing symptoms. However, when the virus jumps to domestic poultry—such as chickens, turkeys, and quail—it can mutate into a more virulent form. This mutation process often occurs in environments where wild and domestic birds interact, especially near shared water sources or poorly biosecured farms.

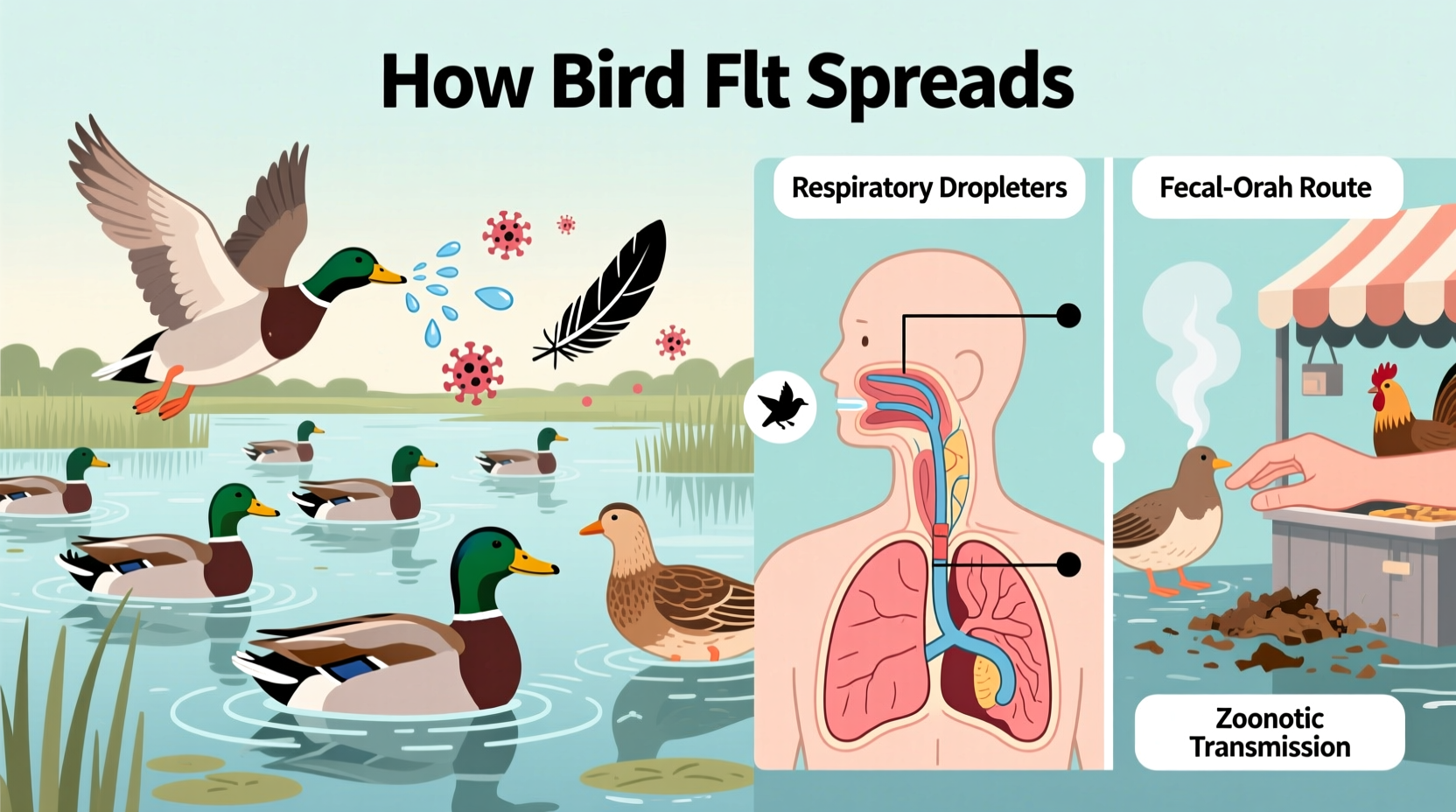

Primary Transmission Pathways of Bird Flu

The transmission of bird flu occurs through several interconnected routes. Understanding these helps mitigate risks for both animal and human populations.

Direct Contact with Infected Birds

The most common way bird flu spreads is through close physical interaction with infected birds. This includes handling sick poultry, touching contaminated feathers, or inhaling aerosolized particles from bird droppings. Farmers, veterinarians, and backyard flock owners are at higher risk due to frequent exposure.

Contaminated Environments and Fomites

Fomites—objects or materials that carry infection—are major contributors to the indirect transmission of avian influenza. Equipment like egg trays, crates, boots, and vehicles can transport the virus across farms and regions. Even manure used as fertilizer may harbor live virus particles if derived from infected flocks.

Research shows that the H5N1 virus can remain infectious in cool, moist environments for up to 30 days. This longevity increases the likelihood of environmental persistence, especially in shaded soil or stagnant water.

Airborne Transmission Over Short Distances

In dense poultry operations, airborne transmission can occur over short distances (up to 1–2 kilometers) via dust or respiratory droplets. While not considered the primary mode, this route has been documented during large-scale outbreaks, particularly in areas with poor ventilation and high stocking densities.

Migratory Birds and Global Spread

Wild bird migration plays a critical role in the global dissemination of avian influenza. Species such as mallards, teals, and swans travel thousands of miles annually along established flyways—like the East Asian-Australasian Flyway and the Atlantic Flyway—carrying the virus across continents.

During stopovers at lakes, marshes, and agricultural fields, infected birds excrete the virus into water bodies. Other birds, including domestic ducks and shorebirds, then become infected by drinking or bathing in contaminated water. Satellite tracking and genetic sequencing have confirmed that outbreaks in Europe and North America often correlate with the arrival of migratory birds from Asia.

| Transmission Route | Risk Level | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Direct contact with infected birds | High | Use PPE; avoid handling sick birds |

| Contaminated water sources | High | Cover water tanks; prevent wild bird access |

| Fomite transmission (equipment, clothing) | Moderate | Disinfect tools and footwear regularly |

| Airborne spread in poultry houses | Moderate | Improve ventilation and spacing |

| Migratory bird introduction | Variable | Monitor local bird activity; report die-offs |

Human Risk and Zoonotic Potential

While bird flu does not spread easily between humans, certain strains—including H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6—have demonstrated zoonotic capabilities. Most human cases result from prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected poultry, such as during slaughter, defeathering, or cleaning coops.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there have been over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 since 2003, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. However, sustained human-to-human transmission remains rare, limiting pandemic potential—for now.

Public health agencies monitor mutations closely, as changes in the virus’s hemagglutinin protein could enable easier binding to human respiratory cells. Such an adaptation would increase the risk of efficient person-to-person spread, potentially triggering a global outbreak.

Impact on Wildlife and Ecosystems

Beyond poultry, avian influenza affects a wide range of bird species. Recent outbreaks have led to mass mortality events among raptors, gulls, cormorants, and even marine mammals like seals and sea lions, indicating cross-species spillover.

In 2022, an H5N1 outbreak killed tens of thousands of seabirds at colonies in Scotland and Canada. Similarly, endangered species such as the Caspian tern and the Hawaiian goose (nēnē) have faced population-level threats due to localized infections.

Ecologists warn that repeated epizootics (animal epidemics) could disrupt food webs and alter migratory patterns. For instance, if predator birds decline due to illness, rodent populations might surge, affecting agriculture and biodiversity.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Effective prevention hinges on robust biosecurity practices, especially for poultry farmers and backyard bird keepers.

- Isolate domestic birds: Keep chickens and ducks separated from wild birds by using netted enclosures and covered runs.

- Control access: Limit visitors to poultry areas and require disinfection of shoes and hands before entry.

- Sanitize equipment: Regularly clean feeders, waterers, and coops with veterinary-approved disinfectants (e.g., bleach solutions or iodine-based cleaners).

- Monitor health: Watch for signs of illness—lethargy, decreased egg production, swollen heads, or sudden death—and report suspicious cases to authorities immediately.

- Vaccinate when appropriate: In some countries, vaccination programs exist for high-risk regions, though they are not universally adopted due to trade implications and variable efficacy.

For wildlife managers, surveillance is key. Programs like the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Poultry Improvement Plan and the European Union’s Wild Bird Surveillance Network track virus presence through routine sampling of hunter-harvested and found-dead birds.

Role of Climate and Seasonality

Seasonal patterns influence the timing and intensity of bird flu outbreaks. Cooler temperatures enhance virus stability, making autumn and winter peak periods for transmission. Additionally, fall and spring migrations coincide with increased intermingling between wild and domestic birds, raising the risk of viral introduction.

Climate change may exacerbate this trend. Warmer winters allow some waterfowl to shorten migrations or overwinter closer to poultry farms, increasing contact opportunities. Changes in precipitation patterns can also create temporary wetlands that attract mixed bird populations, serving as hotspots for viral exchange.

Regional Differences in Outbreak Management

Responses to avian influenza vary significantly by region, depending on regulatory frameworks, farming density, and surveillance capacity.

In the United States, the USDA coordinates outbreak responses, including quarantine zones, depopulation of infected flocks, and compensation for farmers. In contrast, many Southeast Asian countries rely heavily on live bird markets, which pose persistent transmission risks due to crowded conditions and inadequate sanitation.

European nations follow strict EU regulations requiring immediate reporting, culling within 24 hours of confirmation, and movement restrictions within 10-kilometer protection zones. Meanwhile, African and South American countries often face challenges due to limited diagnostic infrastructure and informal poultry trade networks.

Travelers and bird enthusiasts should consult national agricultural or wildlife agencies for real-time updates. Websites like the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) and the CDC provide current maps and alerts on active outbreaks.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how bird flu spreads, leading to unnecessary fear or complacency.

- Misconception: Eating poultry or eggs spreads bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked meat and pasteurized eggs do not transmit the virus. Heating to 70°C (158°F) kills influenza pathogens. - Misconception: All bird deaths indicate avian flu.

Fact: Many diseases and environmental factors cause bird mortality. Laboratory testing is required for confirmation. - Misconception: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Ducks, turkeys, parrots, and even raptors can be infected, though symptom severity varies.

What Birdwatchers and Nature Lovers Should Know

For those who enjoy observing birds in the wild, the risk of contracting avian influenza is extremely low. However, responsible practices help protect both people and wildlife.

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds. Use gloves and masks if handling is necessary (e.g., for research).

- Do not feed waterfowl in areas with known outbreaks.

- Clean binoculars, cameras, and boots after visits to wetlands or reserves.

- Report clusters of dead birds to local wildlife authorities.

Organizations like Audubon Society and BirdLife International offer regional advisories and promote citizen science initiatives to monitor avian health trends.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can humans catch bird flu from watching birds?

No, simply observing birds in nature does not pose a risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated materials.

How long can bird flu survive in water?

The virus can remain infectious in cold water for up to 30 days, though survival time decreases rapidly in warm, sunny conditions.

Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

A pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine exists in limited supply for emergency use, but no widely available commercial vaccine is currently recommended for the general public.

Can pets get bird flu?

Cats can become infected by eating raw infected birds, though cases are rare. Dogs appear less susceptible. Keep pets away from sick or dead wildlife.

What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not handle it barehanded. Contact your local wildlife agency or health department for guidance on reporting and disposal.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4