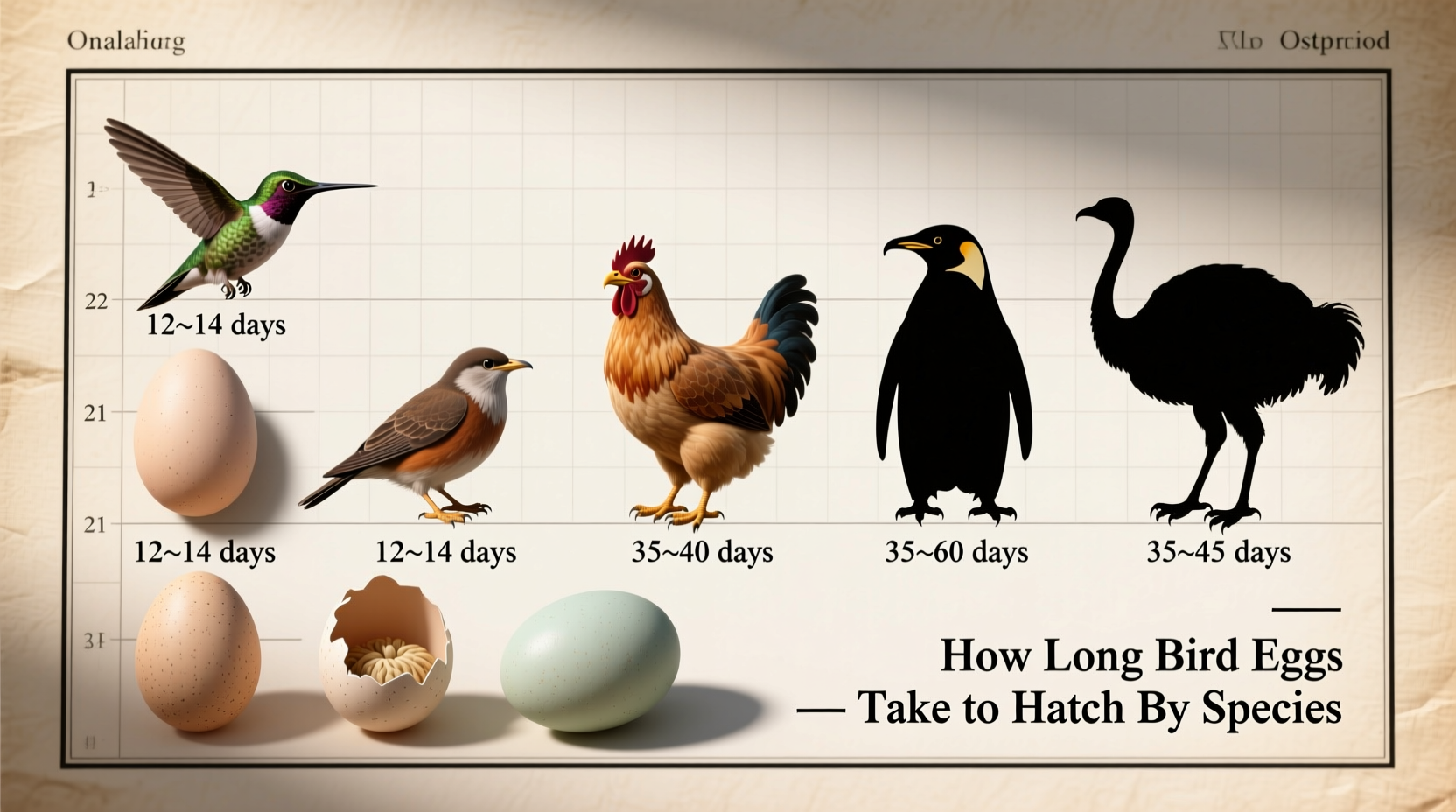

The time it takes for bird eggs to hatch varies widely depending on the species, but generally ranges from about 10 days for small songbirds like finches to over 80 days for large birds such as albatrosses. This period, known as the incubation period, is influenced by factors including egg size, ambient temperature, and parental behavior. Understanding how long does it take for bird eggs to hatch provides valuable insight into avian development, breeding patterns, and ecological adaptations across different environments.

Understanding the Incubation Period Across Bird Species

Incubation is the process by which adult birds keep their eggs warm to ensure proper embryonic development. The duration of this phase is closely tied to a bird’s metabolic rate, body size, and evolutionary niche. Smaller birds typically have shorter incubation periods due to faster metabolism and quicker embryonic growth. In contrast, larger birds with slower metabolic rates require more time for their young to fully develop inside the egg.

For example, the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) incubates its eggs for approximately 12–14 days, while the tiny Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) requires only 11–14 days despite its minuscule egg size. At the other end of the spectrum, Emperor Penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) endure an impressive 64–67 days of incubation in the harsh Antarctic winter, during which males balance the egg on their feet under a brood pouch.

Typical Hatching Times by Common Bird Groups

To better understand variation in hatching times, let's examine average incubation durations across several major bird families. These values are based on field observations and ornithological studies conducted globally and represent typical ranges under natural conditions.

| Bird Species | Average Incubation Period (Days) | Nest Type | Primary Incubator |

|---|---|---|---|

| House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) | 10–14 | Cavity/Nest box | Female |

| Blue Tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) | 13–16 | Tree cavity | Female |

| Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) | 14–15 | Flimsy platform | Both parents |

| European Robin (Erithacus rubecula) | 13–15 | Shrub or crevice | Female |

| Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) | 30–37 | Abandoned nest | Female |

| Barn Owl (Tyto alba) | 29–34 | Cavity/building | Female |

| Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) | 25–28 | Ground nest | Female |

| Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) | 34–36 | Large stick nest | Both parents |

| Emperor Penguin | 64–67 | No nest (on feet) | Male |

| Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans) | 76–81 | Ground mound | Both parents |

This table illustrates that incubation length increases significantly with body size and life history strategy. Altricial birds—those born naked, blind, and helpless—often have shorter incubation times relative to precocial species, which hatch more developed and mobile.

Factors That Influence Egg Hatching Time

While species is the primary determinant of incubation length, several environmental and behavioral variables also play crucial roles:

- Egg Size: Larger eggs contain more yolk and require longer development periods. For instance, ostrich eggs—among the largest laid by any living bird—take about 42 days to hatch.

- Temperature: Embryonic development is highly temperature-dependent. If ambient temperatures drop too low, development slows or stops. Conversely, excessive heat can be lethal.

- Parental Attendance: Some birds, like pigeons and doves, maintain near-constant contact with their eggs, leading to consistent development. Others may leave eggs unattended for extended periods, slightly prolonging effective incubation.

- Altitude and Climate: Birds nesting at high elevations may experience cooler temperatures, requiring longer incubation unless compensated by increased parental effort.

- Clutch Size: In some species, larger clutches result in slightly asynchronous hatching because incubation begins before all eggs are laid.

The Role of Parental Behavior in Successful Hatching

Birds employ various strategies to regulate egg temperature. Most passerines (perching birds) develop a brood patch—an area of bare, highly vascularized skin on the belly that transfers heat efficiently to the eggs. Both males and females may possess this adaptation, though it's often more pronounced in the primary incubator.

In many raptors and waterfowl, both parents share incubation duties. This allows one bird to forage while the other guards and warms the clutch. In contrast, male Emperor Penguins perform sole incubation, fasting for weeks while balancing the egg on their feet beneath a feathered abdominal fold.

Turning the eggs regularly is another critical behavior. Parents instinctively roll or reposition eggs to prevent the embryo from adhering to the shell membrane and to ensure even heat distribution. This behavior has been replicated in artificial incubators used in conservation programs.

Development Stages Inside the Egg

Avian embryology follows a predictable sequence. Within 24 hours of fertilization, cell division begins. By day 3–4, the heart forms and starts beating. Limb buds appear around day 5–6, followed by feather development and organ maturation. In the final days, the chick positions itself with its beak toward the air cell at the blunt end of the egg.

Hatching itself is an energy-intensive process. Using a temporary structure called the egg tooth—a small calcified protuberance on the tip of the beak—the chick begins to pip, or crack, the shell. This process, known as pipping, may take several hours to over a day. Once free, altricial chicks are entirely dependent on parental care, while precocial species like ducks and chickens can walk and feed themselves shortly after hatching.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Egg Hatching

Several myths persist regarding bird reproduction and hatching timelines:

- Myth: All birds lay eggs daily until the clutch is complete, then begin incubating.

Truth: While common in many species (e.g., robins), some birds start incubation immediately after the first egg, resulting in staggered hatching. - Myth: Touching a bird’s egg will cause the parents to reject it.

Truth: Most birds have a poor sense of smell and will not abandon eggs simply because they’ve been handled—though unnecessary disturbance should still be avoided. - Myth: Eggs will hatch exactly on schedule.

Truth: Variability in temperature, humidity, and parental attentiveness means hatching can occur a day or two earlier or later than expected.

Observing Hatching: Tips for Birdwatchers and Backyard Enthusiasts

If you're observing a nesting bird, patience and minimal interference are key. Here are practical tips for those interested in witnessing hatching:

- Identify nesting stages: Learn when your local species typically breed and how long incubation lasts. Field guides and apps like Merlin Bird ID or eBird provide regional data.

- Avoid close approach: Frequent disturbances can stress parents or attract predators. Use binoculars or a telephoto lens instead.

- Monitor from a distance: Note when incubation began (usually after the last egg is laid in multi-egg clutches) and calculate the expected hatch window.

- Do not attempt to assist hatching: Even if a chick seems stuck, intervention can cause harm. Hatching is a natural struggle that helps clear fluid from the lungs.

- Support native habitats: Provide safe nesting sites through birdhouses, native plants, and predator control (e.g., keeping cats indoors).

Artificial Incubation and Conservation Efforts

In wildlife rehabilitation and endangered species programs, artificial incubators simulate natural conditions to increase hatching success. Organizations like the Peregrine Fund and San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance use controlled temperature (typically 99–102°F or 37–39°C), humidity (50–65%), and automatic egg turners to mimic parental care.

Such techniques have been instrumental in recovering populations of species like the California Condor and Whooping Crane. However, hand-rearing carries risks, including imprinting and reduced survival upon release, so natural incubation is always preferred when possible.

Regional and Seasonal Differences in Hatching Timing

Hatching times can vary geographically even within the same species. For example, House Wrens in southern regions may begin nesting as early as March, with eggs hatching in 12–15 days, while northern populations may not start until June due to delayed spring conditions.

Climate change is also affecting avian phenology—the timing of biological events. Studies show that many temperate-zone birds are laying eggs earlier in the year to align with earlier insect emergence, which directly impacts when eggs hatch and chicks must be fed.

What Happens After Hatching?

The post-hatch period is critical for survival. Altricial nestlings remain in the nest for days to weeks, being fed frequently by both parents. Songbirds may make hundreds of feeding trips per day. Precocial chicks, like those of killdeer or quail, leave the nest within hours and follow their parents to learn foraging skills.

Nestling diets are typically high in protein—mostly insects—to support rapid growth. Fledging (leaving the nest) occurs once flight feathers develop and muscles strengthen, usually 10–21 days after hatching in small birds, but up to 10 weeks in eagles and owls.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How can I tell if a bird egg is viable?

- Viable eggs are usually opaque when candled (shined with a bright light in a dark room), showing visible blood vessels and embryo movement after a few days. Cold, clear, or foul-smelling eggs are likely non-viable.

- Do all eggs in a clutch hatch at the same time?

- Not always. If incubation starts with the first egg, hatching is asynchronous. If it begins after the last egg is laid, hatching tends to be synchronous.

- Can cold weather delay hatching?

- Yes. Prolonged exposure to cold slows embryonic development. Parents compensate by increasing brooding time, but extreme conditions can lead to developmental issues or mortality.

- How long after pipping does a chick fully emerge?

- Pipping to full emergence typically takes 12–48 hours, depending on species and chick strength. It's a strenuous process requiring rest between efforts.

- Is it legal to collect or move wild bird eggs?

- In most countries, including the U.S. under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, it is illegal to possess, move, or disturb wild bird eggs without a permit.

Understanding how long it takes for bird eggs to hatch enriches our appreciation of avian life cycles and supports responsible observation and conservation. Whether you're a backyard birder or a seasoned ornithologist, recognizing the delicate balance of time, temperature, and parental care involved in hatching offers a deeper connection to the natural world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4