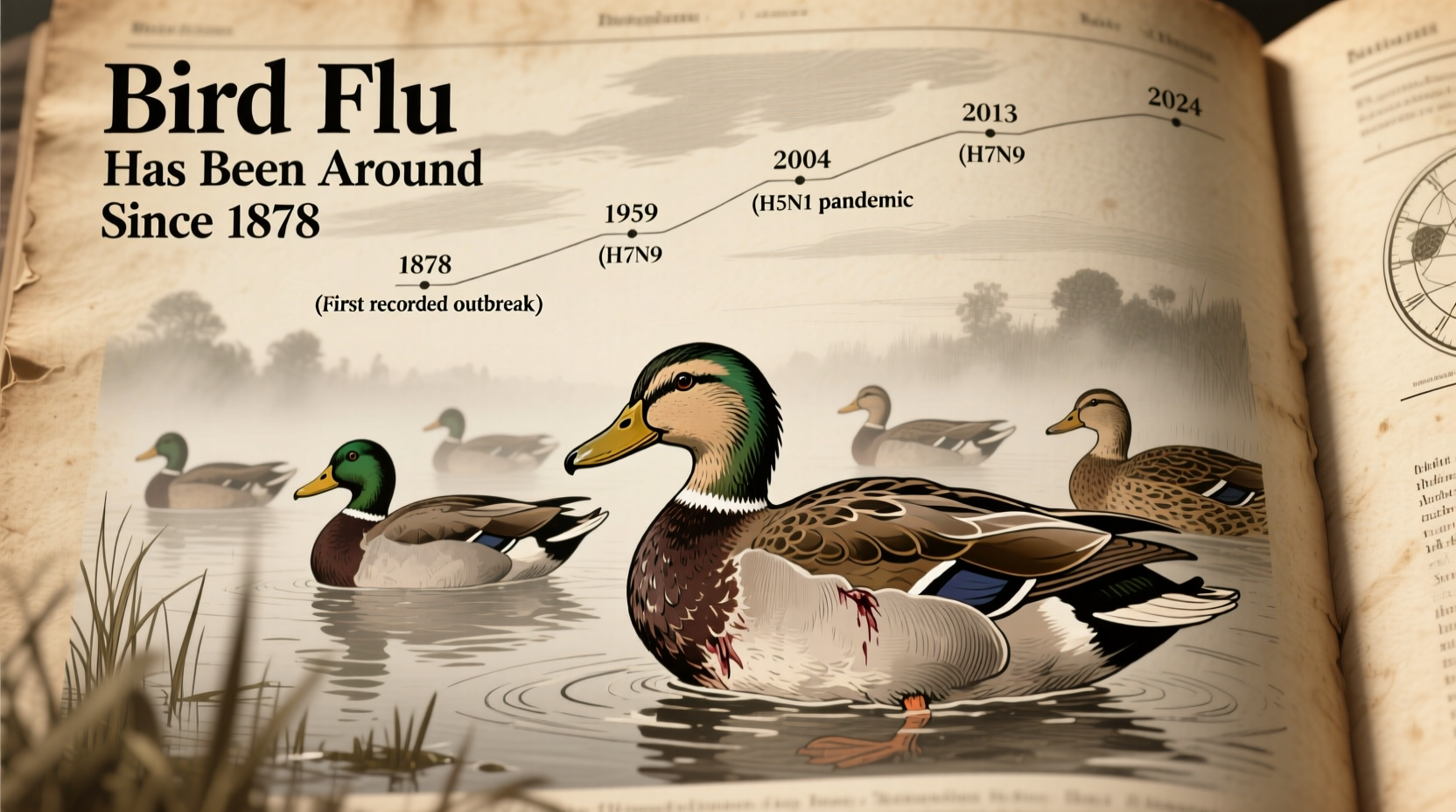

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, has been around for over a century, with the first recorded outbreak dating back to 1878 in Italy. Understanding how long avian influenza has existed helps contextualize its evolution and global impact. The virus responsible for bird flu belongs to the influenza A family and primarily affects birds, though certain strains can cross species barriers and infect humans. Over time, the duration and persistence of bird flu have led to recurring outbreaks across continents, making it one of the most closely monitored zoonotic diseases in veterinary and public health circles. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'how long has the bird flu been around historically' reflects widespread interest in both the timeline and biological significance of this disease.

Historical Origins and Early Documentation

The earliest documented case of what we now recognize as bird flu occurred in 1878 when an illness devastated poultry flocks in northern Italy. At the time, it was referred to as "fowl plague," a term used before scientists understood viral etiology. It wasn't until the 1950s that researchers classified the causative agent as an influenza A virus. This historical milestone marked the beginning of modern virology's engagement with avian influenza. By tracing how long the bird flu has been around through scientific records, we see that while the virus has existed for more than 140 years, our understanding of its mechanisms, transmission, and subtypes has evolved significantly.

Throughout the 20th century, sporadic outbreaks were reported globally, particularly in commercial poultry farms where high-density bird populations facilitated rapid spread. These early events laid the foundation for surveillance systems and biosecurity protocols still in use today. Recognizing how long avian influenza has circulated among bird populations underscores the importance of long-term monitoring and international cooperation in disease control.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Biology and Transmission

Avian influenza viruses are categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, resulting in numerous combinations, some of which pose greater risks than others. High-pathogenicity strains like H5N1 and H7N9 are of particular concern due to their ability to cause severe disease and death in birds—and occasionally in humans.

Birds, especially waterfowl such as ducks and geese, serve as natural reservoirs for low-pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) viruses. These birds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, enabling silent spread during migration. When LPAI mutates into highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), the consequences for domestic poultry can be devastating, leading to mass culling and economic losses.

Transmission occurs through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, including feces, saliva, and respiratory secretions. Humans typically contract the virus through close proximity to sick birds, although human-to-human transmission remains rare. Still, the potential for mutation raises concerns about pandemic risk, reinforcing why tracking how long the bird flu has been around is critical for predictive modeling and vaccine development.

Major Outbreaks and Global Impact

One of the most significant milestones in the history of avian influenza was the emergence of the H5N1 strain in 1996 in Guangdong, China. This high-pathogenicity variant began infecting humans in 1997, marking the first known instance of bird flu causing fatal illness in people. Since then, H5N1 has caused multiple waves of infection across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America, prompting widespread culling of poultry and strict import restrictions.

In 2014–2015, the United States experienced its worst bird flu outbreak to date, affecting over 50 million turkeys and chickens across 15 states. The primary strain involved was H5N8, introduced via migratory birds from Asia. This event highlighted vulnerabilities in industrial farming practices and spurred investment in faster diagnostic tools and improved containment strategies.

More recently, starting in 2021, a new wave of H5N1 infections has swept across wild and domestic bird populations worldwide. As of 2024, this ongoing epizootic has reached over 80 countries, including regions previously unaffected. The scale and duration of this outbreak underscore how long avian influenza has adapted and persisted within global ecosystems.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds in Disease Narratives

Birds have long held symbolic roles in human culture—representing freedom, spirituality, and omens. However, during pandemics, these same creatures can become symbols of fear and contagion. The association of migratory birds with the spread of avian influenza has influenced public perception, sometimes unfairly stigmatizing species like crows or pigeons despite their minimal role in transmission.

In literature and media, birds often appear as harbingers of change. During the 2005 H5N1 scare, news headlines frequently depicted ominous images of dark flocks flying across skies, evoking apocalyptic imagery. While such portrayals raise awareness, they can also fuel misinformation. Educating the public about how long the bird flu has been around—not as a sudden threat but as a persistent ecological phenomenon—helps counteract sensationalism and promotes science-based responses.

Indigenous knowledge systems in various parts of the world have long recognized patterns in bird behavior linked to environmental changes. Some communities report altered migration routes or unusual bird deaths preceding disease outbreaks. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern surveillance could enhance early warning systems and deepen our understanding of avian influenza dynamics.

Current Surveillance and Prevention Strategies

Given how long avian influenza has circulated, robust surveillance is essential. International organizations like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborate to monitor outbreaks and share data in real time. Programs such as OFFLU (OIE/FAO Network of Expertise on Animal Influenza) facilitate research and coordinate response efforts.

On the ground, prevention relies heavily on biosecurity measures:

- Isolating domestic flocks from wild birds

- Disinfecting equipment and transport vehicles

- Monitoring bird health daily

- Reporting suspicious deaths immediately

Vaccination is used selectively, mainly in countries with large poultry industries. However, vaccines do not eliminate the virus; they reduce symptoms and shedding, which can mask transmission. Therefore, vaccination must be paired with rigorous testing and movement controls.

| Strain | First Identified | Host Range | Human Cases | Mortality Rate (Humans) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1996 | Birds, cats, humans | ~900+ | ~50% |

| H7N9 | 2013 | Poultry, humans | ~1,600 | ~40% |

| H5N8 | 2014 | Birds only | 0 | N/A |

| H9N2 | 1966 | Poultry, rare human cases | Few | Low |

Practical Guidance for Birdwatchers and Poultry Keepers

For birdwatchers, the persistence of avian influenza means adopting responsible practices:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds; report them to local wildlife authorities.

- Clean binoculars, feeders, and clothing after visits to wetlands or reserves.

- Follow regional advisories—some areas may temporarily close birding trails during outbreaks.

Poultry owners should implement strict biosecurity protocols:

- Limit visitor access to coops.

- Use dedicated footwear and clothing when handling birds.

- Source chicks from certified disease-free hatcheries.

- Stay informed through national agricultural departments and veterinary services.

Both groups benefit from staying updated via official channels rather than social media rumors. Knowing how long the bird flu has been around reminds us that vigilance, not panic, is the appropriate response.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza, often stemming from confusion over its longevity and transmission:

- Misconception: Eating properly cooked poultry spreads bird flu.

Fact: The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Misconception: All bird flu strains infect humans.

Fact: Most strains remain confined to avian species. - Misconception: Culling is excessive and unnecessary.

Fact: Rapid elimination of infected flocks prevents wider economic and health crises.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

As climate change alters migration patterns and intensifies extreme weather events, the dynamics of avian influenza transmission may shift. Warmer temperatures could extend the survival of the virus in the environment, while habitat loss forces wild and domestic birds into closer contact.

Ongoing research focuses on universal influenza vaccines, genomic sequencing for early detection, and AI-driven models predicting outbreak hotspots. Scientists are also studying how long the bird flu has remained viable in different ecosystems—from frozen lakes in Siberia to tropical wetlands in Southeast Asia—to refine containment strategies.

Public education remains key. Emphasizing that bird flu is not new—that it has been around since at least the late 19th century—helps frame current challenges within a historical context. This perspective supports informed decision-making and reduces reactionary policies.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When was bird flu first discovered?

- The first recorded outbreak of bird flu, then called fowl plague, occurred in 1878 in Italy.

- Can humans get bird flu?

- Yes, but only certain strains like H5N1 and H7N9 have caused human infections, usually through direct contact with sick birds.

- Is bird flu still active today?

- Yes, as of 2024, H5N1 continues to circulate in wild and domestic bird populations worldwide.

- How is avian influenza monitored globally?

- Through international networks like WOAH, FAO, and CDC, which track outbreaks and share genetic data to guide responses.

- Does cooking chicken kill the bird flu virus?

- Yes, proper cooking at temperatures above 70°C (158°F) destroys the virus, making poultry safe to eat.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4