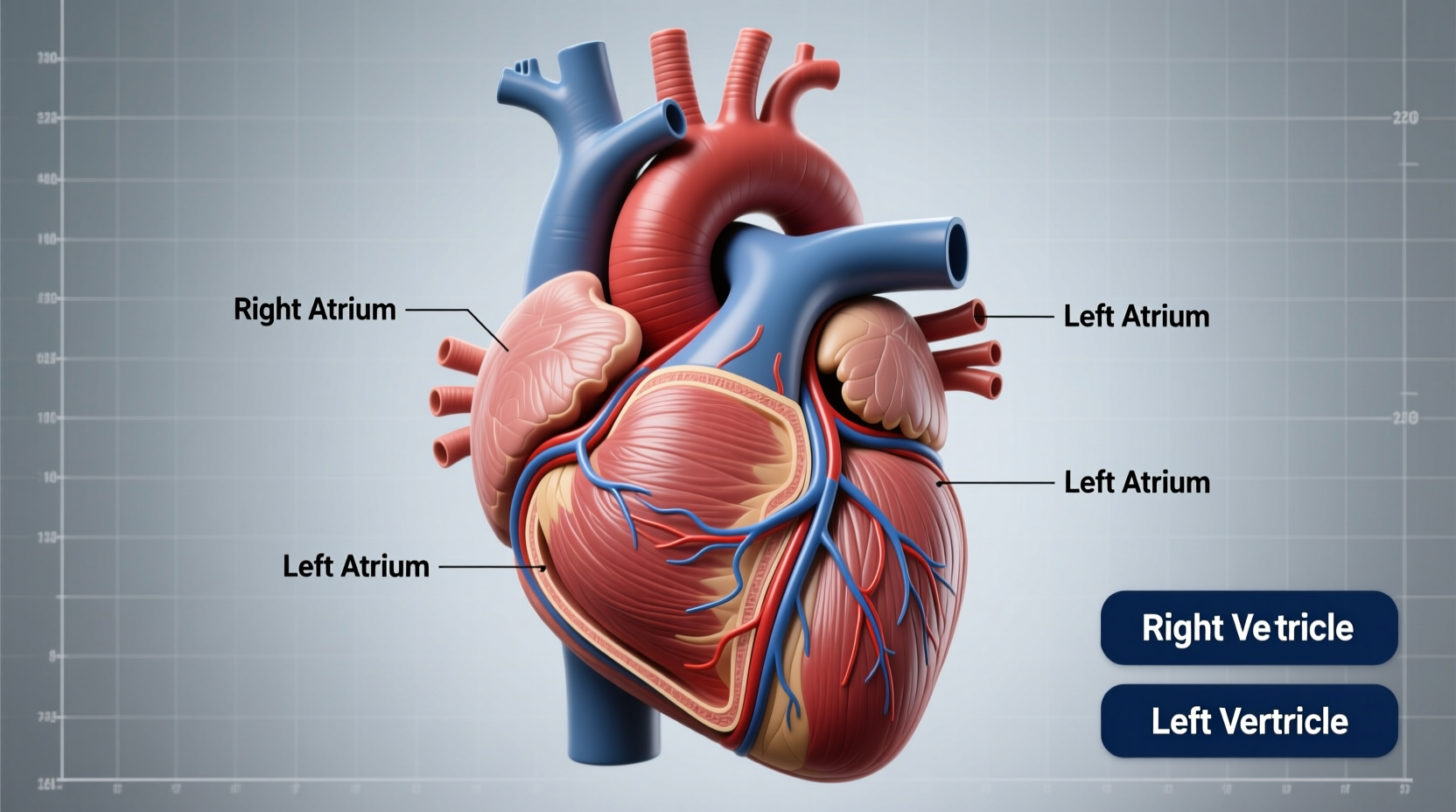

A bird’s heart has four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. This anatomical feature is central to understanding how birds sustain the high metabolic rates required for flight, thermoregulation, and endurance. When exploring the question of how many chambers does a bird heart have, it's essential to recognize that this four-chambered structure is a key evolutionary adaptation shared with mammals, despite birds being non-mammalian vertebrates. The presence of a complete septum between the left and right sides of the heart ensures that oxygenated and deoxygenated blood do not mix, allowing for highly efficient circulation—critical for meeting the energetic demands of avian life.

Evolutionary Significance of the Four-Chambered Heart in Birds

The evolution of the four-chambered heart represents a major milestone in vertebrate physiology. While reptiles typically possess a three-chambered heart (with two atria and one partially divided ventricle), birds and mammals independently evolved fully separated ventricles. This convergence suggests strong selective pressure for enhanced circulatory efficiency.

In birds, the need for sustained aerobic activity—especially powered flight—demands an exceptionally efficient cardiovascular system. Flight is one of the most energy-intensive forms of locomotion in the animal kingdom. To support this, birds require rapid oxygen delivery to muscles, efficient carbon dioxide removal, and precise thermoregulation. The four-chambered heart enables a double circulatory system: pulmonary circulation sends deoxygenated blood to the lungs, while systemic circulation delivers oxygen-rich blood to the body.

This separation prevents the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, maximizing oxygen uptake and utilization. In contrast, animals with incomplete septa (like some amphibians or non-crocodilian reptiles) experience partial mixing, which reduces aerobic capacity. Thus, the answer to 'how many chambers does a bird heart have' isn’t merely anatomical—it reflects deep physiological and ecological adaptations.

Comparative Anatomy: Birds vs. Mammals vs. Reptiles

Understanding how many chambers a bird heart has becomes even more insightful when compared across vertebrate classes:

| Class | Heart Chambers | Ventricular Separation | Circulatory Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aves (Birds) | 4 (2 atria, 2 ventricles) | Complete | Very High |

| Mammalia | 4 (2 atria, 2 ventricles) | Complete | Very High |

| Reptilia (non-crocodilian) | 3 (2 atria, 1 ventricle) | Partial | Moderate |

| Amphibia | 3 (2 atria, 1 ventricle) | None | Low to Moderate |

| Fishes | 2 (1 atrium, 1 ventricle) | N/A | Low |

Interestingly, crocodilians—birds’ closest living relatives among reptiles—also have a four-chambered heart, reinforcing the idea that this trait evolved within the archosaur lineage, which includes dinosaurs, pterosaurs, crocodiles, and birds. This supports the hypothesis that high-performance physiology was already present in some Mesozoic reptiles before modern birds emerged.

Physiological Advantages of a Four-Chambered Heart in Avian Species

The four-chambered design offers several distinct advantages crucial to avian survival:

- High Metabolic Rate Support: Birds have some of the highest metabolic rates among vertebrates. Smaller species, such as hummingbirds, can have heart rates exceeding 1,200 beats per minute during flight. The efficient separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood ensures consistent delivery of oxygen to tissues.

- Endothermy (Warm-Bloodedness): Like mammals, birds are endothermic, meaning they generate internal heat to maintain a constant body temperature. This requires continuous energy production, supported by a robust circulatory system capable of delivering fuel and oxygen rapidly.

- Altitude Tolerance: Many bird species migrate at high altitudes where oxygen levels are low. Bar-headed geese, for example, fly over the Himalayas at elevations above 29,000 feet. Their hearts must pump oxygen efficiently under hypoxic conditions—a feat made possible by the precision of their four-chambered circulation.

- Sustained Aerobic Activity: Unlike most reptiles, which rely on anaerobic bursts, birds engage in prolonged aerobic exertion. Whether soaring, flapping, or hovering, their muscles depend on steady oxygen supply, facilitated by the dual-pump system of the heart.

Structure and Function of the Avian Heart

The avian heart, though similar in chamber count to mammals, exhibits unique structural features adapted to flight:

- Proportionally Larger: Relative to body size, bird hearts are significantly larger than those of most mammals. For instance, a hummingbird’s heart may constitute up to 2.5% of its total body mass—compared to about 0.5% in humans.

- Faster Heart Rates: Resting heart rates vary widely by species but generally exceed mammalian norms. A resting sparrow might have a pulse of 500 bpm; in flight, it can surpass 1,000 bpm.

- Compact Shape: The avian heart is more compact and elongated than the human heart, fitting tightly within the thoracic cavity beneath the keel (sternum). This positioning minimizes movement during wing beats.

- Efficient Valves and Myocardium: Strong myocardial walls, especially in the left ventricle, generate high pressure for systemic circulation. Valves prevent backflow, ensuring unidirectional flow through both circuits.

Bird Heart Health and Lifespan Considerations

Despite their high metabolic output, many birds live surprisingly long lives. Parrots and albatrosses can exceed 50–60 years. This longevity raises questions about cardiac resilience. How does a heart beating so rapidly avoid premature wear?

Research indicates that avian cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells) have superior mitochondrial density and antioxidant defenses compared to mammals. Additionally, birds exhibit lower levels of oxidative stress despite high oxygen consumption, possibly due to more efficient electron transport chains in mitochondria. These traits help protect against arrhythmias, fibrosis, and other age-related heart conditions common in mammals.

Observing Bird Hearts: Challenges and Scientific Methods

Direct observation of a functioning bird heart is challenging due to small size and rapid rhythms. Scientists use various techniques to study avian cardiovascular function:

- Doppler Echocardiography: Non-invasive ultrasound imaging allows real-time assessment of heart structure and blood flow in live birds.

- Electrocardiograms (ECG): Used in research and veterinary medicine to monitor electrical activity, detect arrhythmias, and assess fitness.

- Dissection Studies: Post-mortem anatomical studies provide detailed insights into heart morphology across species.

- Respirometry Coupled with Cardiovascular Monitoring: Measures oxygen consumption alongside heart rate to evaluate metabolic efficiency.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Hearts

Several myths persist regarding avian anatomy and physiology:

- Misconception: "Birds have faster hearts because their hearts are less efficient."

Reality: Quite the opposite—they have highly efficient hearts optimized for performance. Rapid rates reflect high demand, not inefficiency. - Misconception: "All reptiles have three-chambered hearts, so birds must be different."

Reality: Crocodiles and alligators have four-chambered hearts, showing that this trait predates birds and evolved in shared ancestors. - Misconception: "Since birds lay eggs, they can't be warm-blooded or have advanced hearts."

Reality: Reproduction method doesn’t determine thermoregulation or heart structure. Birds are fully endothermic with advanced circulatory systems.

Implications for Birdwatchers and Conservationists

While most birdwatchers focus on plumage, song, and behavior, understanding underlying physiology enriches appreciation of what makes birds extraordinary. Observing swifts dive at 100 mph or warblers cross oceans nonstop becomes more awe-inspiring when one considers the cardiovascular engine powering these feats.

For conservationists, knowledge of avian heart health informs efforts to assess population fitness. Environmental stressors—such as pollution, habitat loss, or climate change—can impact cardiovascular performance. Elevated heart rates due to chronic stress may signal declining well-being in wild populations.

Practical Tips for Learning More About Bird Physiology

If you're intrigued by the question of how many chambers does a bird heart have and want to explore further:

- Visit natural history museums with comparative anatomy exhibits.

- Enroll in ornithology courses offered by universities or online platforms like Coursera or edX.

- Read peer-reviewed journals such as The Auk, Journal of Avian Biology, or Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology.

- Participate in citizen science projects like eBird or Project FeederWatch, which often include educational modules on bird biology.

- Consult field guides that include anatomical diagrams, such as Handbook of Bird Biology by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all birds have four-chambered hearts?

Yes, all modern bird species have four-chambered hearts. This is a defining characteristic of the class Aves.

Why do birds need four chambers in their heart?

The four-chambered heart allows complete separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, supporting high metabolic demands for flight, endothermy, and endurance.

Is a bird’s heart bigger than a mammal’s?

Proportionally, yes. Relative to body size, bird hearts are generally larger than those of most mammals, especially in small, active species like hummingbirds.

Can you hear a bird’s heartbeat?

With a stethoscope and a calm, cooperative bird (often in veterinary settings), it is possible. However, their rapid heart rate makes individual beats difficult to distinguish without training.

Are birds mammals since they have four-chambered hearts?

No. Despite sharing a four-chambered heart and endothermy with mammals, birds are a separate class (Aves) distinguished by feathers, beaks, egg-laying, and skeletal adaptations for flight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4